Scientists Believe They Found God Particle

Scientists at the Large Hadron Collider say the particle outlined in July 2012 looks increasingly to be a Higgs boson.

The Higgs, long theorised as the means by which particles get their mass, had been the subject of a decades-long hunt at the world's particle accelerators.

Yet there is still some uncertainty as to whether the particle is indeed a Higgs, and if so, what type it is.

Results at the Moriond meeting in Italy suggest strongly that the particle's "spin" is consistent with a Higgs.

Teams from the two Higgs-hunting experiments, Atlas and CMS, analysed two-and-a-half times more data than were available in July in an effort to pin down not only the particle's existence, but also something about its character.

All that is conclusively established is that the particle is in the family of bosons, but researchers had been careful since July to describe it as "Higgs-like".

'New story'

The zoo of subatomic particles are characterised by properties including their "spin" and "parity" - and the precise establishment of these properties for the new particle will determine if it is beyond doubt the long-sought Higgs.

What is more, theories predict that a number of different types of Higgs may exist.

The simplest form - that which fits neatly into the existing Standard Model of particle physics - would surely shore up the theory, but the possible existence of more "exotic" versions of the particle would open exciting new vistas in science.

"This is the start of a new story of physics," said Tony Weidberg, Oxford University physicist and a collaborator on the Atlas experiment.

"Physics has changed since July the 4th - the vague question we had before was to see if there was anything there," he told BBC News.

"Now we've got more precise questions: is this particle a Higgs boson, and if so, is it one compatible with the Standard Model?"

The results reported at the conference - based on the entire data sets from 2011 and 2012 - much more strongly suggest that the new particle's "spin" is zero - consistent with any of the theoretical varieties of Higgs.

"The preliminary results with the full 2012 data set are magnificent and to me it is clear that we are dealing with a Higgs boson, though we still have a long way to go to know what kind of Higgs boson it is," said CMS spokesperson Joe Incandela.

As is often the case in particle physics, a fuller analysis of data will be required to establish beyond doubt that the particle is a Higgs of any kind. But Dr Weidberg said that even these early hints were compelling.

"This is very exciting because if the spin-zero determination is confirmed, it would be the first elementary particle to have zero spin," he said.

"So this is really different to anything we have seen before."

Even more data will be required to explore the question of more "exotic" Higgs particles.

A popular but as-yet unsubstantiated theory called supersymmetry suggests there should be as many as five Higgs particles - a notion that will have to remain speculative at least until new data are acquired after the LHC's two-year shutdown for refurbishment.

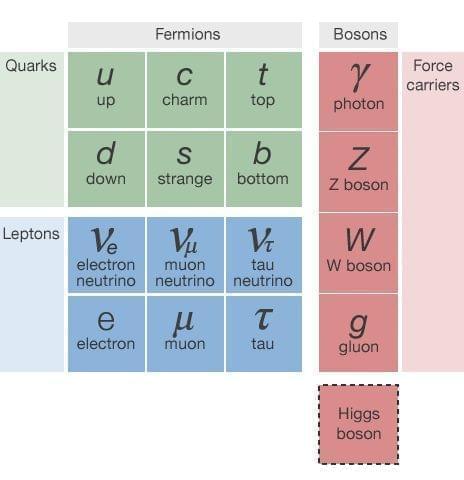

The Standard Model and the Higgs boson

• The Standard Model is the simplest set of ingredients - elementary particles - needed to make up the world we see in the heavens and in the laboratory

• Quarks combine together to make, for example, the proton and neutron - which make up the nuclei of atoms today - though more exotic combinations were around in the Universe's early days

• Leptons come in charged and uncharged versions. Electrons - the most familiar charged lepton - together with quarks make up all the matter we can see; the uncharged leptons are neutrinos, which rarely interact with matter

• The "force carriers" are particles whose movements are observed as familiar forces such as those behind electricity and light (electromagnetism) and radioactive decay (the weak nuclear force)

• The Higgs boson came about because although the Standard Model holds together neatly, nothing requires the particles to have mass; for a fuller theory, the Higgs - or something else - must fill in that gap