How An Engineer From Illinois Risked His Career To Make Apollo 11 A Success

__large.jpg)

Courtesy of Audible

Fifty years ago this week, the first man walked on the moon. A new book tells the story of an airplane engineer from Illinois some consider to be an unsung hero in making that happen.

John Houbolt grew up in Joliet, studied engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and eventually worked his way to NASA. It’s there in the early 1960s that he put his career on the line to champion what was, at the time, an unpopular idea for sending humans to the moon, but would ultimately lead to the success of Apollo 11 on July 20, 1969.

That’s according to Todd Zwillich, author of the new Audible Original, “The Man Who Knew The Way To The Moon.”

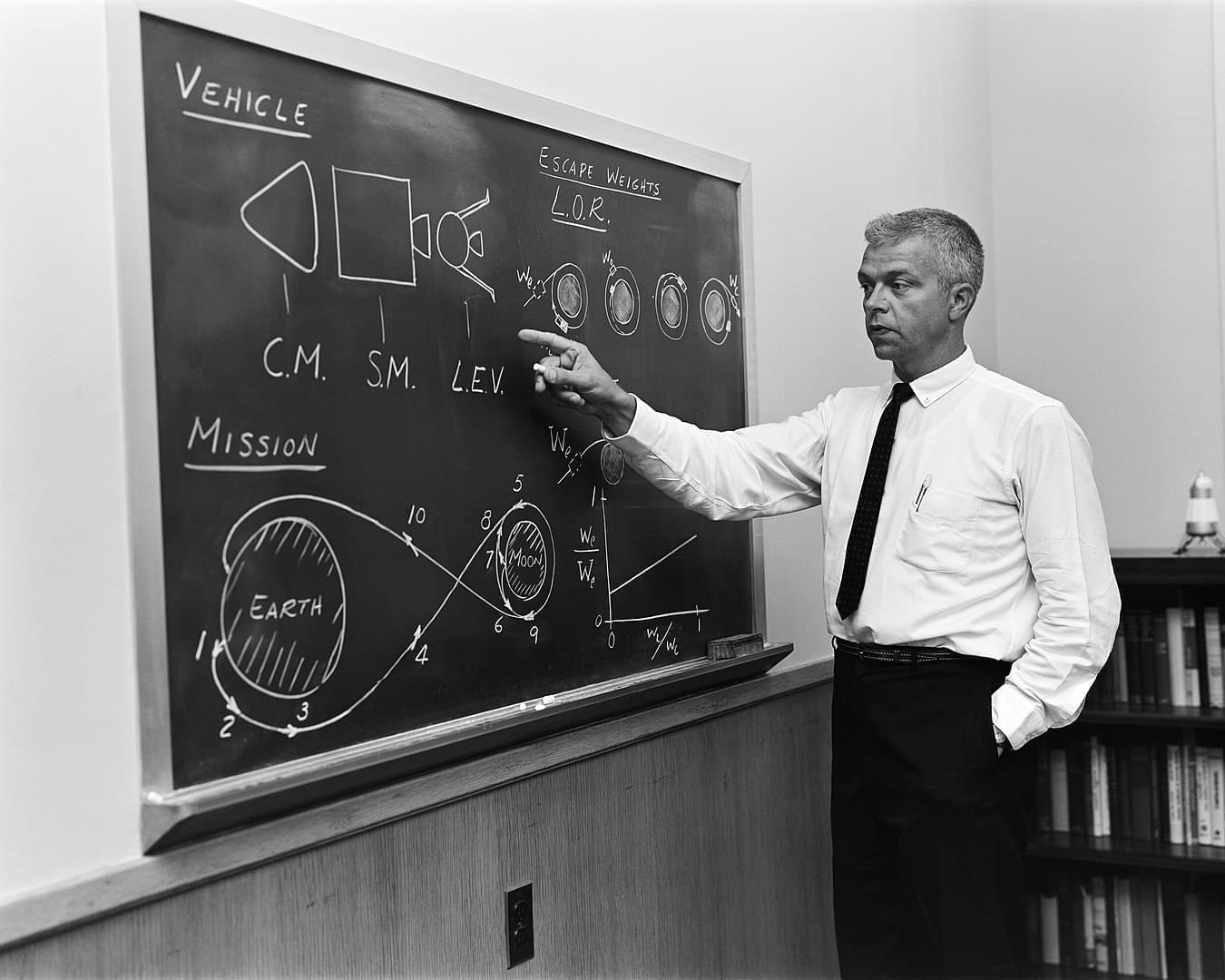

John Houbolt explaining his Lunar Orbital Rendezvous plan for landing on and returning from the moon, to be used in the then-nascent Apollo program.

The book tells the story of Houbolt, who is credited with championing the idea of "Lunar Orbit Rendezvous,” the concept of launching a spacecraft into orbit around the moon, and from there, sending only a small, lightweight craft down to the moon’s surface, instead of the entire rocket.

While Houbolt didn’t invent the idea of Lunar Orbit Rendezvous, Zwillich said, he was the one who started to apply it to the technologies that were within NASA’s grasp at the time.

Zwillich spoke with Illinois Public Media about his new book.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You describe John Houbolt as an unsung hero in the first moon landing. Can you take us back to the early 1960s, and explain how he came to play a critical role in Apollo 11?

Yeah, and to tell the story, you really do have to go back to the early days. At that time, in the back rooms of NASA engineers are already theorizing and arguing and debating about how they might go to the moon, one day. There was no national program to go to the moon, they were still trying to get Mercury off the ground, literally, you know, trying to race the Russians to get Alan Shepard into space; that wouldn't happen for another year, year and a half or so.

But in the back rooms, they know that probably the moon is going to be a target, at some point. Seems logical. And there are lots of debates flying around about how they're going to go. A lot of the early ideas about how to get to the moon are pretty remarkable; they'll remind you of some of the old movies or comics or books from the 20s, or the 1910s, or the turn of the century, that you might have seen about one day going to the moon.

The main mode of preference at NASA at this time was to launch a giant rocket from the earth, big enough that you stage off pieces of it. It would get to the moon and back that rocket down, butt first, onto the moon for a landing.

John Houbolt got involved in this debate sort of from the side, you know, he was an outsider in this sense. He did work at NASA. But he wasn't an aerospace engineer. No, he was an aeronautical engineer. He was an airplane guy. And he was around the debates, he contributed to a lot of the early data on orbits. We were starting to send satellites up, we knew we were going to try to send humans up. And we needed to understand how objects orbit the Earth, how do you get them in for reentry? John did the calculations on those things. And so he sort of got a foot in the door on these early debates about the moon, even though he wasn't really part of the hierarchy that was making it happen.

John Houbolt is in these backroom saying no, you can't land a big rocket backward on the moon. Number one, it's just dangerous. That rocket has to be 90 or 100 feet tall, it has to be filled with fuel because you need that fuel to get out of the moon's gravity and back home. It could literally tip over, it's not a safe way to do it. But more important in John's eyes, his arguments were: the size of the boosters and the size of that rocket, to take all that mass to the moon, just inefficient. How are we ever going to build a rocket that big?

What was the idea that John Houbolt had?

So John's idea was something different, John said: Lunar Orbit Rendezvous. And what Lunar Orbit Rendezvous says is: don't take all of that fuel, don't take all of that weight down to the moon surface, so that you have to launch it all back home. Why not leave most of it in orbit, leave it up there, take a very lightweight craft down to the moon, not a big unwieldy rocket, but a tiny little lander that the astronauts can steer and can see the surface to land. That's the way you do it.

And the easiest way to understand this, I think, is think of a big ocean ship, you know, exploring a couple hundred years ago. Well, you should get across the ocean in that big ship and carry all your crew and your equipment. But when you get to the shore, you shouldn't drive that big ship right up against the shore; you're going to hit rocks, you're going to hit waves, you're going to wreck your ship. Why not get into a rowboat, a dinghy, and just take the dinghy ashore. And when you're done on the shore, get in your dinghy and go back to the ship. It's really a similar concept. John said, take a small lander down; when you're done exploring, launch back up from the moon, rendezvous -- Lunar Orbit Rendezvous -- in orbit with a mothership around the moon, then go home, save all that weight, save all that mass. That was his argument.

This concept of lunar orbit rendezvous; it wasn't one that he invented. But you write about how John Houbolt was the one who started to apply it to the technologies that were within NASA’s grasp at the time. How was he treated by his colleagues and NASA leaders at the time?

Well, this is one of the most remarkable parts of the story because when John started campaigning hard for this idea, he was grabbing anyone he could. He was grabbing fellow engineers in the hallway, he was grabbing bosses, if they came down to Langley to tour the place, he would grab them on the side and try to lobby them on lunar orbit rendezvous.

And he was going to every meeting that he could. There were tons of committees at this time to talk, debate about modes to go to the moon, to vote on those ideas. And John is really trying to wiggle his way into all of these that he can.

A lot of times John was treated with polite indifference. A lot of times he got the brush off. And other times, he was downright abused. And I'll give you one example that that really stands out, and there are a number of them in the story that I think just will give people pause.

In December of 1960, so very early, we're talking six months before Kennedy challenges the country to go to the moon, John is at a high level meeting of NASA leaders, all the big shots are there. And they're engineers; they're just debating ideas for maybe thinking about a moon mission. Again, the challenge has not been made by the White House. This is just them discussing the issue. And some engineers get up and they talk about this mode of direct ascent: launching the big rocket and landing butt-first on the moon. They talk about another method, which is assembling a spacecraft in orbit than sending that rocket to the moon, that's called Earth Orbit Rendezvous, another contender in the debates. John gets up to talk about rendezvous, which he had some expertise in, and then he throws in a pitch for Lunar Orbit Rendezvous.

All of a sudden, another engineer, a very well known engineer, a guy named Max Faget. He was a renowned engineer, a brilliant man. He designed the Mercury capsule that took John Glenn into space. He later would go on to help design the space shuttle, so he was a heavy-hitter engineer. Max Faget hears John's presentation on Lunar Orbit Rendezvous and shoots out of his seat. He stands up and he pounds the table in front of everyone and he says don't listen to Houbolt; his figures lie. He accused John of being a liar in front of everyone, in front of all of his colleagues. This was a humiliating, embarrassing experience for John, one that I can tell you, you'll hear in the story, he never forgot, not for the rest of his life. He carried these scars.

There are other incidents as well that you will hear in the story. But the answer is John faced a mixture of indifference at times, abuse and at times ridicule that he never forgot, until things started to change and engineers started to realize his data might be right.

I mentioned John Houbolt is a native of Illinois and you came here for part of your research and reporting process for this book. Where did you go and who did you talk to?

Oh, that was a great trip. Well, I started in Champaign-Urbana at the University of Illinois, John's proud alma mater for his undergraduate engineering degree. John's papers are housed in the historical archives at University of Illinois. So I came there for a couple of days, worked with the archival staff there who were just wonderful, dug into 60 boxes of John's records.

John C. Houbolt at blackboard, showing his space rendezvous concept for lunar landings. Lunar Orbital Rendezvous (LOR) would be used in the Apollo program. Although Houbolt did not invent the idea of LOR, he was the person most responsible for pushing it at NASA.

And I'll tell you, it was eye opening. John was a meticulous individual and the amount of material that he kept -- of course, his academic papers, his engineering papers, his sketches, his drawings -- and correspondence, professional, personal, personal receipts, notes, travel vouchers, arguments with other people, letters that he scrawled to other characters in this story when they were having disagreements, but he never mailed them. It appeared that he was just blowing off steam. Keeping inventory of his decision, along with his wife Mary, about whether or not they should move to New Jersey at one point. I mean, the man kept it all. It's all housed there at the University of Illinois.

So I was there, I went to Joliet, which is John's hometown where he grew up the son of servants. His father was a was a caretaker. His mother was a cook for a wealthy local senator in Joliet, they spent their lives in the servants quarters on Senator Barr's estate in Joliet, Illinois. I visited that town, I visited John's relatives who still live in the area, some of them in Joliet, some of them in Ransom, Illinois, population 400, about 20 minutes outside of Joliet; his nephews were wonderful to me. And a little bit of time in Chicago as well on that trip.

A trip to Illinois to really try to get the sense of where john came from, you know, he put himself through junior college at Joliet Junior College, he was very proud of it. He put himself through University of Illinois. This was a young man who was born onto a farm, and he absolutely hated it. His parents had nothing when he was a little boy, his parents were immigrants from Holland, his father came over when he was just 16 to try to find a new life. He was a tenant farmer.

John was one of these people you hear about who was very unhappy with his station in life as a young boy, and he was determined to get out of it. And he got himself out of it, he realized that he had engineering and mathematical capability and he put it to use, he got out of there and got himself to NASA.

As you look back at what was happening in the 1960s, and what's happening today in terms of renewed efforts to get back to the moon, and ultimately to Mars, what are some of the similarities you see?

Oh, I think it's remarkable. You know, NASA has changed an awful lot. This is a story in John's day, let's be honest, of a whole lot of old dead dudes, old dead guys, you know, and that's fine. That's the way NASA was at the time. John's wife, Mary is a big part of this story as well, I do want to tell you that she has a fascinating story. Mary was a human computer at NASA Langley in the 40s, just like the Hidden Figures of the book and the movie; not just like, she's not African American, not a "hidden figure" in that sense. But she was in the same operation a number of years before. And she has a fascinating story.

You ask about today, and NASA has really made a big effort to change the face of people outwardly facing to sell the public on its missions, and to hire a lot more women, and a lot more minorities into the STEM fields. And so they're doing that, some of them are in this story as well.

That's only a small part of it. On the technical side, the debates that John went through: How do we go to the moon? How do we manage the fuel that will need and the mass that will need? How do we actually land and actually come back? Well, in John's day, the idea of doing a rendezvous around the moon, at first, was unheard of. They had never tried rendezvous when he was trying to sell them on this issue. They had never tried it around the Earth. Here comes John Houbolt to say, let's try it around the moon 250,000 miles away. Part of the reason why people were terrified of him and of his data at first.

Today, we know that that can work because we've done it, of course, and the administration says we're heading back to the moon. The debates over how exactly we do that our starting all over again. And in some cases, they're very similar to those in John's day, because physics doesn't change.

How do we get the mass that we'll need for some of the bigger things? We want habitats, we want vehicles. Will we want refueling capability on the moon? We're going to have to manage all of that mass. How much of it? Do we park in orbit? And how much of it do we send directly to the moon?

When you talk about Mars, gosh, 150 million miles, on average, orders of magnitude of a bigger problem. Do we do some form of Martian orbit rendezvous? Do we build a station in Martian orbit that we can stage down to the surface to manage all that mass, prevent you having to go directly to the Martian surface, try to slow down in that thin Martian atmosphere and then launch to come back home. A lot of problems to think about. And because the physics hasn't changed, the basics of the debates that John went through 60 years ago in the hallways of NASA are really starting all over again.