Homemaker

by Holly Yacoumakis

See the Timeline

"One voice I know many homemakers will recognize is that of Jessie Heathman of the University of Illinois Home Economics Extension, who presents a daily program, For You at Home..."

This is how Hugh Cordier introduces Miss Heathman (as she will be known for all of her adult life), assistant extension editor for the College of Agriculture and a fellow broadcaster at WILL.

It is December 1, 1949, and Heathman is the host of two daily radio shows in the Illinois area (By 1957, she will produce, write, and star in a TV show on WILL-TV as well). She edits articles for departmental newsletters and she travels all across Illinois to teach home economics courses. “Some weeks I travel 5 to 600 miles,” she claims during this interview. It’s a plausible estimate. At the time, the University was acquiring ever more automobiles to encourage instructors to teach class off-campus.

This particular exchange is an instance of bubbly promotional filler for the Home Economics extension programming on WILL. Cordier and Heathman talk about past shows and planned events; entertainingly, they weave in dialogue about “Oodles of Noodles,” a popular Jimmy Dorsey number that will be broadcast on the next episode of “The Pops Concert”.

Something significant happens here, too. Heathman delivers the motto of the Home Economics extension service:

"The home should be the center of every woman's efforts, but not the circumference."

Beyond the Doorstep

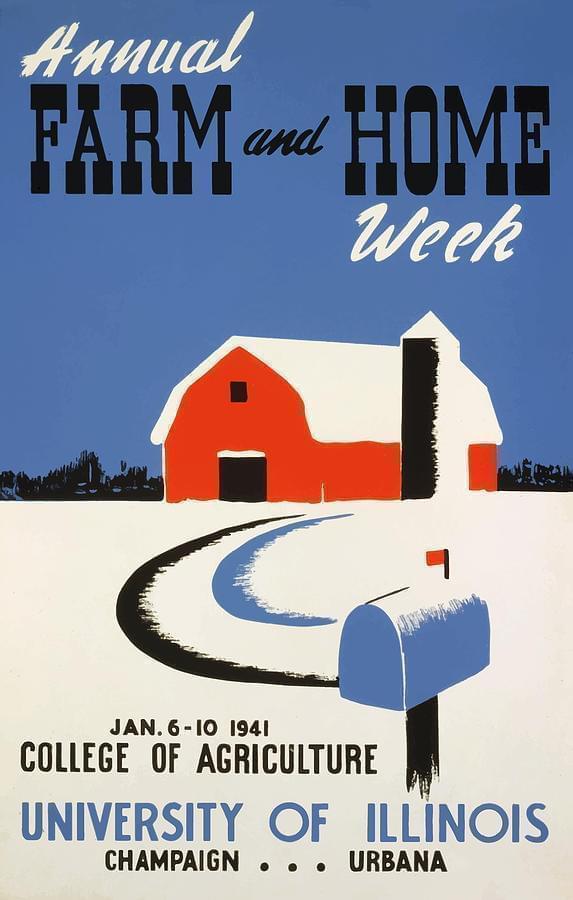

In February, 1951, the University of Illinois will hold its Fiftieth Annual Farm and Home Week. During the event, Mrs. Catherine Pendleton (Charles) De Shazo, the Secretary of the Associated Women of the American Farm Bureau, makes an assertion that is nearly identical to Heathman’s. Observing that “everything that happens beyond our home affects the home,” she asks her audience to look “a little beyond our doorstep.”

The women who called themselves homemakers in the 1950s are often considered a circumscribed bunch. But we should not discount Heathman. We should not discount De Shazo.

In an era before “the personal is political” became the mantra of feminists, Heathman was a professional home economist, lecturer, and broadcaster. She could not resist the urge to cautiously step up to the soapbox. Listen to these two, and you discover that they were not placid or neutral or contained in some devoted hermetic lifestyle. Quite the opposite extreme, in fact.

I hear Heathman as a contradiction. She proclaims the domestic sphere to be the right and proper place for women, but she violates that boundary at every opportunity. She is a successful career woman whose domain happens to be the home.

Maybe the work of a seamstress is an appropriate metaphor: Like most Americans, Heathman is on a quest to stitch her dueling identities into one cohesive cloth. The seams, she hopes, will be invisible.

But this idea of “the circumference” gets at something messier.

Speaking for Themselves

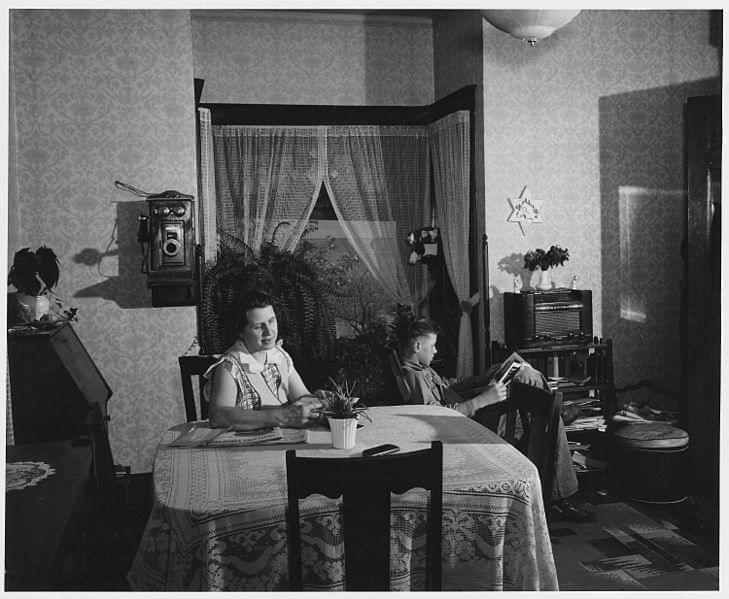

On one episode of The Homemaker's Quarter Hour, Heathman interviews two married couples that attend the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. "We're going to let these young people speak for themselves," she tells the audience, as she proceeds to interrogate the quintet.

"First of all is it wise for young married women to have a profession in addition to homemaking, and if so, is home economics training a good choice?"

Honestly asked and answered, these questions would have been meaty and controversial.

The reality is this: Mr and Mrs. Chuck Pollard and Mr. and Mrs. Lee Price were not speaking for themselves. Their responses are familiar, canned, predetermined ones. The dialogue is a soothing checklist that allows married women to have careers as home economists without granting them too much dangerous autonomy.

"She has an opportunity to understand the husband's problems if she has a profession of her own," says Chuck. She can "provide business and social acquaintances for the husband." Furthermore, “as a home economics teacher she can train her own children much better."

She will avoid developing a “mother complex” from staying at home, where technology has made her obsolete, bored, and unstimulated.

"There's so much carry over between your job or your profession and your homemaking activities,” says one girl. “And what you learn in one place you can carry over to the other place."

Finally: "the husband and wife can marry at an earlier age if the wife is also training for a profession."

The Pollards and the Prices make rote responses. It is not their agenda to reflect or philosophize, and it is perhaps unfair to expect them to do so. They're busy trying to live their lives.

But we can reflect. This is the beauty of the archives. The 21st century listener has the advantages of hindsight. If, like Heathman, we struggle to piece all our contradictory identities together, it must be a comfort to know that some future audience might at least recognize those struggles.

Reconstructing Farm and Home

In subsequent years, Heathman will broadcast live from Farm and Home Week. We do not have preserved copies of these live broadcasts. But we do have a handful of recordings from Heathman’s daily shows. We have another handful of the lectures performed by other participants at Farm and Home Week. We have articles with insights into Heathman’s life and beliefs. And, for further illumination, we have Hadley Read's published memoir, detailing a golden era at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign's Office of Agricultural Communications.

With all of this, it is possible to rethread a moment in America’s recent past when the farm and the home were just beginning to splinter. These conversations at Farm and Home Week were reflected in the projects that Heathman did for the Home Economics division. Listening to them, I begin to understand a few things about our changing national character between the Depression and the widespread adoption of second wave Feminism. It becomes apparent that our impression of 1950s American comfort, confidence, and conformity glosses over a substrate of complexities and anxieties.

The WILL archive includes speakers from a diverse community of farmers, agricultural researchers, academics, educators, journalists, politicians, extension service providers, and, yes, home economists. They were all, without exception, saying surprising things. During Farm and Home Week we hear uncertainty, discord, and disagreement. We hear human beings attempting to cope with suburbanization, mechanization, globalization, the entrance of women into the workplace, the capabilities of mass communication, the intersection of education and commercial marketing, youth delinquency, and a food surplus that was decreasing earnings in Illinois and elsewhere. As these conversations make clear, it was not a straightforward path. None of the stakeholders could have foreseen the country that would emerge.

The Circumference

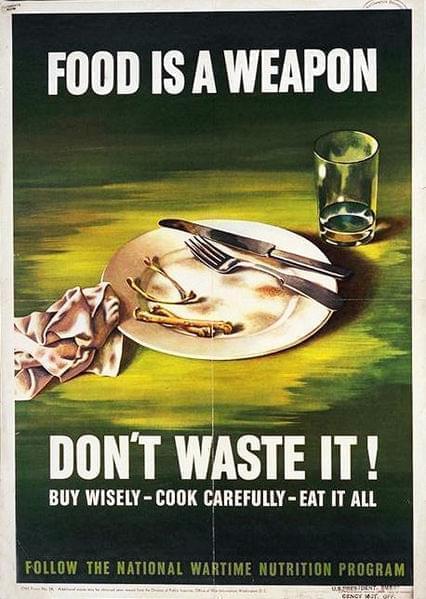

We can add another excerpt to the words of Heathman and De Shazo, this one also from the Farm and Home Week program of 1951. It is from George D. Stoddard, the president of the University of Illinois. He speaks before a gathering of farmers, agricultural scientists, and faculty members, and he reminds them of a World War II slogan: "Food Will Win the War."

President Stoddard is applying the phrase to America’s next war. Not the war against the Axis powers, but the war against Communism, what he calls “an immediate and terrible danger." In between Heathman’s interview with Cordier and Stoddard’s speech, the U.S had become engaged in its first battle with North Korean nationals. The military and the public are poised for action.

On the program guide, President Stoddard's lecture is titled "What the University means to the Farm Family." Jessie Heathman attends as a member of the Publicity and Radio Committee.

She may be listening as Stoddard expands on his theme until it incorporates the epic advance of Communism and the recent history of global poverty. He mentions Korea, of course, as well as China, Russia, India, countries in the Near East, Europe, Africa, and Southeast Asia. He tells the story of the atomic bomb, developed by academic researchers in American universities (It is a weapon Stoddard endorses: proof-positive of American scientific achievements). Communism will be defeated, he asserts, with food, technology, and ideology. If those things fail, it will be defeated with military research and military might.

In this context, he introduces the University’s new research partnership with the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), an international body, based in Washington D.C, designed to confront international hunger and, implicitly, spread democracy.

"Our tremendous knowledge, our tremendous know-how...to use the slang expression...of production and distribution and preserving and freezing and drying and shipping, of how to get from the plant seed...until we finally get meat on the table, all this tremendous knowledge and all its intricacies...as we develop that, we develop this great strength! Which we don't think, at this time, our enemy."

Communist regimes, he argues, entice the common people by offering meager but sufficient subsistence to thousands of impoverished citizens. The United States, with its “know-how,” and its rapidly developing production methods, its efficient tools, and now, with its communication capacities, could win the allegiance of these masses.

Stoddard does not downplay the humble family farm in his victory story. He does not downplay the role of women. Of all the scholastic work and innovative research he observes in an academy renowned for Agricultural Science, he rather remarkably ends his speech with an endorsement of a publication distributed by the Home Economics extension service:

"I am impressed every time I read it with this report of the Home Economics division. This particular one is called A Handbook for Home Economics Students. I wish you could all get a copy of it. Here I go, spending some the state's money, distributing several hundred or several thousand copies of this booklet."

It’s a bizarre moment to me. Over 62-years later, I am sitting in a cubicle, listening to Stoddard’s digitized voice.The university president has started a lecture about the university and the farm family, took a sharp left turn towards war and Communism, and then proceeded to praise the feminine field of domestic science.

The Feminine Field of Domestic Science

When I listen to the full 1951 lecture performed by Mrs. De Shazo of the Associated Women of the American Farm Bureau, I find it even more alarming. It is officially titled “The American Family in Today’s World.” A good portion of it is devoted to instructing listeners on how they should prepare for a nuclear winter and an extended war with communists, both without and within the national borders. "Today we are faced with the greatest and at the same time the most insidious enemy that has faced man since the Garden of Eden,” she cautions.

"This time the serpent offers golden apples of security, Security through Socialism. Security through Communism. The job of the family is to grade these apples, to separate the handpicked from the windfalls. To detects the spicks and the rotten cores. And just as the inspector trains for his job, so must the American citizen train for his."

This rhetoric foreshadows the Red Scare that would characterize the next decade in the United States. It also casts the family as a sort of militia squad: alert, well-ordered, and patriotic. They were not just words. The recasting of the family had a demonstrable effect on how children were raised and families were managed.

Raising Children Right

During several segments of Homemaker’s Quarter Hour, Heathman interviews high school economics teachers and their students. The girls are asked to repeat the lessons they’ve learned. Based on stereotypes alone, one might expect to hear about pie-baking or embroidery. But that is not what we hear.

Instead, the girls of Milford High School conduct themselves like amateur social psychologists. They discuss, among other things, “child training,” and psychological methods of disciplining preschool children. The methods rely on the fear of ostracism to encourage conformity. One student, Caroline, relates an experience she had at the preschool the girls were managing:

"The first day, I ask a boy if he didn't want to put his blocks away after he had been playing with them, and he said no. So the second day I said, 'the rest of the children are putting the blocks in the box. I bet you you'd like to help, too.’ And he went right at it."

Caroline’s Home Economics instructor calls it the “positive approach.”

Here too “apples” are being graded. Caroline is learning how to be an apple inspector, and the boy is learning how to be a good, socially conforming apple. The obedience and clean habits they adopt will be an asset for the United States during the chaos of nuclear attack. That seems to be the subtext, whether conscious or unconscious on the part of Heathman and her fellow educators.

Another group of girls interviewed by Heathman are from Cerro Gordo High School. Their theme is “family relations,” especially the behavior of teenagers. Again, the nascent home economists are encouraged to take something like the positive approach, even when their parents won’t let them go out on dates.

It seems that a large swath of future American mothers were trained to raise their children with these methods. And, indeed, we characterize mothers of this era as somewhat passive-aggressive. It is conveniently forgotten that passivity was a technique recommended by professionals, part of the new science of raising children.

Farm and Home

We are talking about a period in recent U.S history when the once-insulated universe of the home was becoming a matter of national and international affairs. In many ways, what citizens did in the privacy of their living room or backyard was assumed to correlate with their patriotism.

Policymakers were obsessed with the activities of housewives. They must have been, considering how often the “erosion of the family” was discussed. This in itself gave women like Heathman and De Shazo a certain kind of power. President Stoddard did not listen to the Homemaker’s Quarter Hour, but he evidently believed in its ability to affect his objectives.

What about the farm? Stoddard asks, “what does the university mean to the farm family?” The relationship between farm and home is left unstated.

I suspect in 1951 the two were one in the same for many people. Mrs. De Shazo begins her own speech by describing her idyllic family-owned farm back in Virginia. It includes a Dutch-colonial house, nestled beneath growing trees, bordered by shrubs and flower beds. Her husband, nephews, elderly parents, and the family dog all live there. The children enjoy driving the tractor out in the fields after school.

But a transformation was under way. Rural homes were becoming suburban. The farm would soon become the subdivision. Or, if the family remained rural, it would likely abandon the practice of farming to large consolidated corporations. From this period forward, only a small percentage of properties would be both farms and homes.

The Changing Homemaker

When I conjure the image of a stereotypical homemaker, I draw on the TV Land conventions I’m familiar with. Her hair is perfectly curled. She wears a necklace of pearls and heels to vacuum the carpet. She purchases family meals at the local supermarket. She is June Cleaver and Marge Simpson. She does not pluck chickens, grow soybeans, or do her laundry by hand. These are, of course, less than precise cliches about farm life. We tend to cast it as somehow underdeveloped or antiquated when in fact, farms have always relied on cutting-edge technology to survive and to communicate.

Listen to the 1945 broadcast of Homemaker's Quarter Hour and you will find a contrast with those women who would be presented on early television sitcoms. In this piece, Heathman talks to Elsie Butler, a 4-H leader in Northern Illinois. 4-H is the National Institute of Food and Agriculture's youth organization, and Mrs. Butler is in charge of local "clothing clinics." During these clinics, young seamstresses received criticism on their handmade clothes from a panel of judges.

Observes Butler:

"A large number of girls used feedsacks in a variety of colors."

I think this conversation reveals which audience Heathman was addressing in those days. These were girls who had access to feedsacks, not mass-produced garments sold in supermalls.

Heathman witnessed a transformation. It changed the nature of her listeners. The women who tuned in at the beginning of the decade would have different lives than the ones who would watch her TV show at the end of the decade.

The Rural Consumer

Nearly twenty years before Heathman airs the ultra-progressive motto of Home Economics on the radio, she gives a local, unrecorded conference presentation. It is 1928. Her lecture is called “Procedure in Starting a Nutrition Project in Rural Schools” (Daily Illini, Jan. 10, 1928). At this point, her concerns were exclusively the lives of rural people. At what point her “circumference” extends, I cannot know for sure.

I do know that by 1956 she was drawn to a very different demographic. “What Will Urban Outlets in Mass Communications Expect of the Extension Program?” she asks the audience during a subsequent speech (AACE 1956).

But before she gets deep into (sub)urbanization, we go back to 1931. The country is fully immersed in the Great Depression, and the University of Illinois' Home Economics extension service releases a booklet called Let's Use Soybeans.

"Soybeans and soybean products are receiving increased attention at the present time when the rationing of many of the protein-rich foods of animal origin has made us aware of the possibility of insufficient protein in our dietaries[…] Soybeans also have a high caloric value due to fat content and have a higher energy value per pound than the other more commonly used legumes, with the exception of peanuts."

Now, compare the publication of these dry but informative facts to Heathman’s 1948 Homemaking News article promoting an upcoming Farm and Home Week lecture. The lecture is called "Weight-Control--How to Get and Keep the Weight You Want":

"Speaker for this opening session is Miss Harriet Barto, associate professor of dietetics. Miss Barto not only trains students in dietetics at the University, but she has also given real service to physicians and lay persons through her practical advice and popular bulletins on the subject. Miss Barto is author of the University of Illinois circular Sane Reducing Diets."

Between 1931 and 1948, the audience of farm wives (in need of home-grown, high caloric energy) has become an audience of consumers (in need of diet tips).

Heathman's Christmas

Which is not to say that Heathman embraced the emerging consumer culture. In many ways, she resisted it.

I am struck, once again, by Heathman’s balancing act. The evidence suggests that she tries to negotiate between her identity as a producer (a home cook, a seamstress, a handcrafter, a writer, and a representative of the farming community) and the interests of her more suburban listeners, those who would rather buy their produce at a grocery store than grow it.

She has a lot to say about Christmas, for example, and how families should go about celebrating the holiday. In the following 1949 segment of Homemaker’s Quarter Hour, she advises parents to limit the sugary snacks they provide at Christmas parties for children. She recommends graham crackers instead of candy. Neighborhood children at your party, she says, should each be allowed to display just one of the gifts they received from their parents. Once the holiday has ended, she has her listeners conserving their wrapping paper.

"I know one home where ribbons and papers are all pressed before they are stored."

She also warns families not burn all their wrapping paper in the furnace at once, presumably a common cause of household fires.

Her advice has nothing to do with navigating merchandise prices based on globally connected networks of commerce. It has nothing to do with recycling and the impact of wrapping paper on the environment.

About a decade later, Heathman edits a Christmas handbook with other members of the extension service. Even though holiday consumerism is undoubtedly climbing, this book still characterizes the season with carols, stories, recipes, and do-it-yourself decorations. From Heathman one discovers that they can “whiten trees or branches” with a cup of lux flakes and 1/2 a cup of water mixed together with an egg beater. To make a tree decoration:

"Paint a face on a clothespin head. Shape fine wire for wings. Tie on crepe paper dress. Paste paper doilies over wire frame. Attach to tree with colored string or ribbon."

Increasing the People's Wants

Where does this noncommittal consumerism put her in relation to President George D. Stoddard and Catherine De Shazo at the 1951 Farm and Home Week?

Did Stoddard’s idea of the farm, the home, and the family resemble Heathman’s version? Did he envision Christmas with graham crackers and one present per child? A clothespin angel? I’m not convinced he did. I’ve proclaimed that Heathman occupied a hesitant place between producer and consumer. Stoddard was less hesitant about the future of Americans. Yet, they were both considering their actions on a global scale. They were both trying to figure out what was best for the nation and the world.

The story Stoddard delivers is, of course, about education. But it is also about how research performed in the university could strengthen capitalism. It is about marketing strategies. It is about how to turn farmers into better consumers. He calls it “increasing the people’s wants.” He compares development in rural Illinois to the the lack of educational, economic, and social progress the Southern rural regions of the United States, where there are fewer land grant institutions and fewer products in circulation:

"[In] the Deep South....people don't have very good schools, they don't have very good roads, they don't have much reading or communicating material. a radio or a refrigerator becomes a great luxury. The idea of the electrification of their work and home facilities is still rather remote for them. Therefore, their needs are small, their income is small, and we get into this vicious economic circle. Low ambition, low level of aspiration, low ability to pay for anything, and obviously, very few things around that anybody will try to sell them."

Stoddard believes that, through communication technology, farmers would indeed become consumers. Heathman, it seems evident, also believed in the power of communication to change lives. And she just happened to be one of the few women with access to such technologies.

The Mission of 330 Mumford

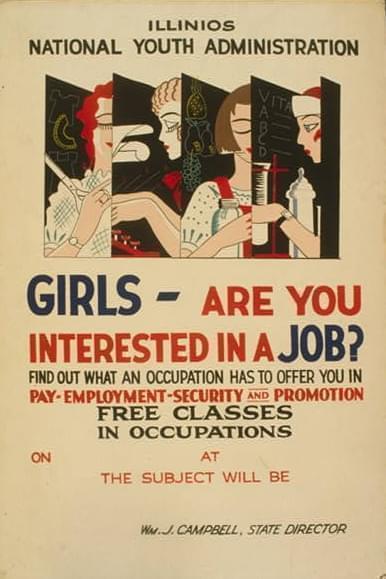

From the perspective of an outsider, it would seem that she was extremely lucky to be a part of the University’s agricultural extension services during some of the department’s zenith years. Hadley Read, the head of the department during that blessed era, characterizes the decades from 1947 to 1968 as overwhelmingly productive. They were also productive for the Home Economics division and for Heathman, who in 1950 was named chairman of the Extension Division of the American Home Economics Association.

In his memoir, Read describes the flurry of activities surrounding Farm and Home Week in 1950. He calls it “the big show for the college”:

"During the week, the office provided advance copy for the 15 visiting newspaper and magazine editors, filed 16,000 words of copy to each of the three press associations, produced 25 live broadcasts, presented two direct broadcasts over WLS in Chicago, and made arrangements for recordings by visiting farm radio editors."

The annual festival usually took place in the first week of February. The staff of 330 Mumford Hall would have spent the winter months churning out typewritten print, exhibit materials, scripts, and pamphlets in preparation for a few days of frenzy. After all, the seven-to-twelve-member editorial staff, including Heathman, had a mission to funnel research conducted at the University to the farmers. In 1949, when Read formulates an official philosophy for his editors in his annual report, he stipulates that “the office must be concerned with guidance, counsel, and training, as much as with production." Home and Farm Week was a rare opportunity to do what they always did, only louder and for the benefit of a national audience that included industry power players.

Heathman gestures toward a similar mission during her interview on WILL. It is the idea of expanding the scope of the department, broadening its sphere of influence: The University, the Agricultural College, the extension services, the home economics division, should all do more and be more in the lives of the public.

Serious Home Ec.

Consequently, her daily guests adopt the tone of researchers, specialists, and scientists. The listener is being informed about results most often derived in controlled experimental studies. It is no accident that Heathman is labeled a “home economist.” Heathman and De Shazo took a serious approach to homemaking practices.

When we describe home economics during these years as soft and frivolous, we forget the fraught role the field attempted to play in mapping human relationships. For better or worse, it borrowed from the emerging fields of social psychology, developmental psychology, sociology, nutrition and health. De Shazo’s Farm and Home Week speech conveniently spells out how she perceives the changes in homemaking practices wrought by home economics:

"Our own America... has evolved from the colonial survival of the fittest to the super scientific laboratory-test formula used by some homemakers today."

Heathman, it may be argued, is more a researcher and a teacher than she is a homemaker. She is unmarried and has no children. Her television show, Your Home and Mine, will be recorded on a set designed to replicate her apartment. It will have a fully furnished kitchen and a dining-living room area. She calls it a place where “anything can happen” (1957). Much as she had done on her radio shows, her character will welcome weekly guest experts to do demonstrations and have discussions. They each participate in the conceit of the show: this stage is Heathman’s apartment. The permanent cast even includes a married couple in the “next apartment”. Heathman puts herself in the home of a career woman, not the home of a wife or mother.

The real Heathman (if she can be separated from her character) is rather anxious about the family home, and, strangely for a woman with a career, she is particularly anxious about women leaving the home. In 1956, she delivers an address at an Agricultural convention that is full of unanswered and unanswerable questions about the future:

"What is the cause for this unrest among women? This desire for release from work that has to do with home and family? Where have we undersold the importance and the dignity of home and family? Are we partially responsible?"

Are they partially responsible? Maybe.

Is there something hypocritical in the question posed by Heathman, who was, in fact, a career woman?

I believe It is more cognitive dissonance than hypocrisy. It is ambivalence.

Heathman’s broadcasts are somewhat dogmatic. They make demands on the listener. This, she implies by carefully guiding her guests, is the right way to decorated your home, raise your children, feed your family. But as rigid as these solutions seem to be on their face, we must acknowledge how fragile and embryonic these new rules were at the time. How to be American, a wife, a woman, a producer, a consumer; how to be an “educated” individual: these were all matters under debate. Stoddard, De Shazo, and Heathman only sound certain.

Heathman left the University of Illinois Agricultural Extension service on August 31, 1968. According to Hadley Read, She moved to Minneapolis-St. Paul and began a new career in television education.

She died in Minneapolis in March of 1981.

Postscript

On December 2, 1964, the Daily Illini mentioned another unrecorded discussion led by Heathman and a few others. She again finds herself talking about careers for women. This time, her audience is the girls of the Theta Sigma Phi National Professional Fraternity for Women in Journalism.

What is the value of a bunch of old archived transcription discs? In a way, they help us solve the cognitive dissonance problem. The Heathman of 1949 put the home at the center of women's lives. We can hear her say it in her own voice. Perhaps by 1964 she believed something different about where women belonged. Maybe she would hardly recognize the words that came out of her mouth in 1949.

Life seems to chip away at everything we think we know from one decade to the next. The changes are gradual. It is only when we pull back, listen to a forgotten past, that we begin to notice what drifting, negotiated, complex identities we occupy.

Bibliography

Written by Heathman

Heathman, Jessie E. "Announce Homemaking Features, Farm and Home Week" Homemaking News for Weeklies (January 20, 1948).

Heathman, Jessie E. What Will They Expect? AAACE 38:11 (September 1956) p. 4.

Heathman, Jessie E. Your Home and Mine: An Experiment with Format AAACE 40:1

Heathman, Jessie E. Writing for Radio Communications Handbook (1967).

Heathman, Jessie E. Family Camps. Recreation 48 (1955): 288.

Newspaper Articles about Heathman

Bureau Delegates Elect Mrs. Moore State’s President. Daily Illini, January 12, 1928.

Bureau Advisers’ Conference Opens. Daily Illini, January 10, 1928.

Theta Sig to Hold Panel. Daily Illini, December 3, 1964.

Obituary for Jessie Ellen Heathman. March 17, 1981.

More Sources

“WILL-TV--Part One of a Special Report.” 1957–1958. Technograph. p. 456

"Let's Use Soybeans" (1931) Department of Home Economics, University of Illinois.

"Fiftieth Annual Farm and Home Week Program" February 5-8, 1951. University of Illinois College of Agriculture.

_-_nara_-_513406.tif.jpg'})