Good news (kinda), bad news (very) from UI researchers about diseases in wild mammals

A northern myotis bat in Monroe County, Illinois, showing the patches of fungus distinctive of white-nose syndrome Steve Taylor / UI Prairie Research Institute

(Please Note: Audio is missing for this story at the moment)

Bad news first. Research by Daniel Raudabaugh, a graduate student in the UI Department of Plant Biology, has confirmed disturbing facts about the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome in bats that hibernate in caves and mines.

Working under the direction of Andrew Miller, a mycologist with the Illinois Natural History Survey, a division of the UI Prairie Research Institute, Raudabaugh conducted experiments to test what kinds of nutrients the fungus could make use of and what kinds of environmental conditions it could tolerate. Other scientists had already observed that the fungus persisted in caves even after bat populations had succumbed to it and there were none of them left for it to live on.

Raudabaugh’s findings help explain why.

Unfortunately, it’s because Pseudogymnoascus destructans is quite flexible. Says Raudabaugh, “It can basically live on any complex carbon source, which encompasses insects, undigested insect parts in guano, wood, dead fungi and cave fish. We looked at all the different nitrogen sources and found that basically it can grow on all of them. It can grow over a very wide range of pH; it doesn’t have any trouble in any pH unless it’s extremely acidic.”

Miller is direct about the upshot of this research. “This means whether the bats are there or not, it’s going to be in caves for a very long time.”

I’d say white-nose syndrome has been a seven-year-long, rolling disaster for North American bats, but that’s an understatement. I simply don’t know the right words to characterize it.

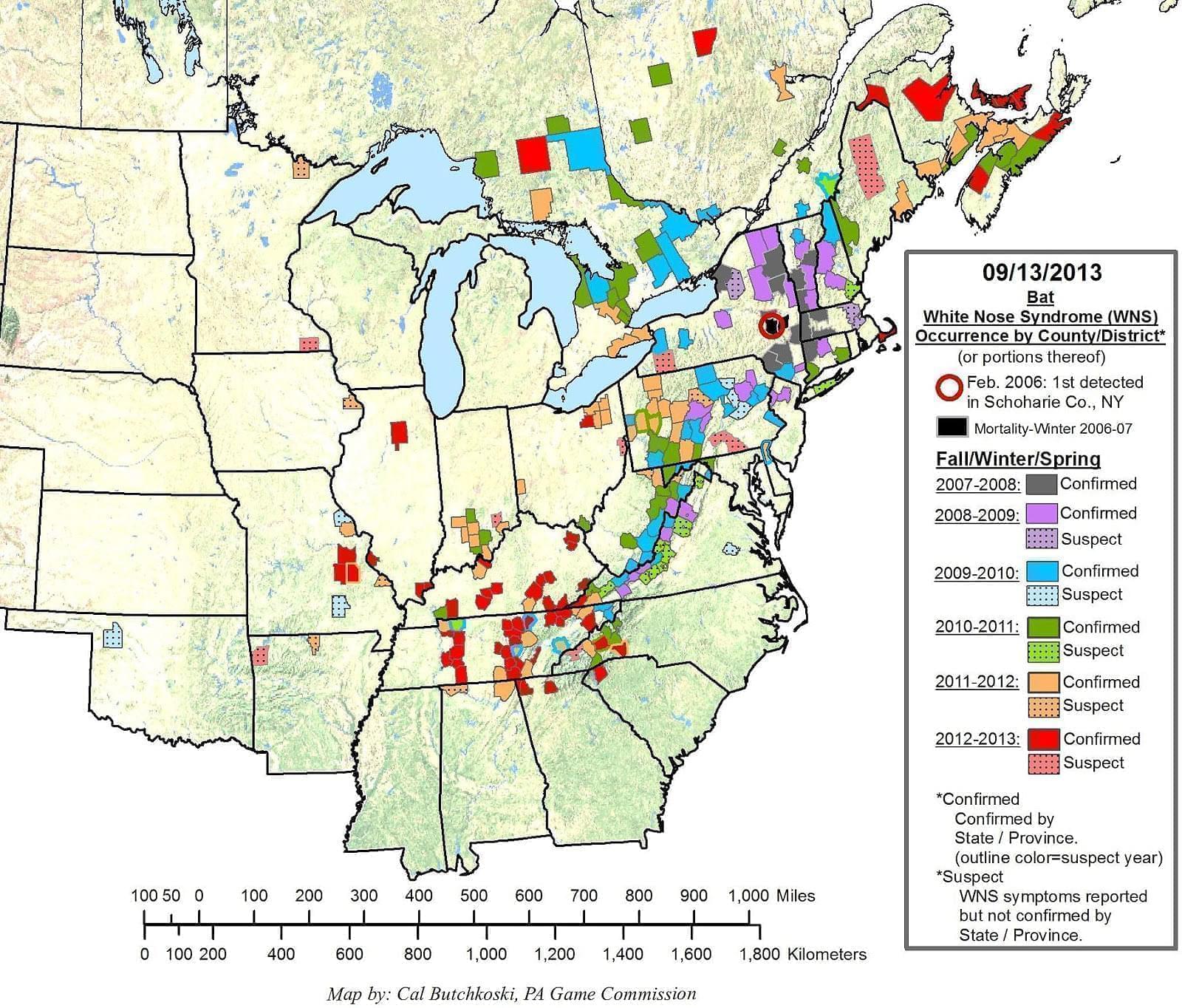

USGS map showing current extent of white-nose syndrome

Prior to 2006, P. destructans occurred in Europe, but did nothing to call attention to itself. That year it arrived in New York State, probably on the clothes or equipment of an unsuspecting caver. Since then, white-nose syndrome (the name given to the affliction caused by the fungus in bats) has spread to at least 24 more states—including Illinois—and five Canadian provinces, and it is estimated to have killed more than 5.7 million bats. It’s not unusual for white-nose syndrome to kill every individual bat at an affected site.

The news is somewhat less depressing on the topic of another wildlife scourge, chronic wasting disease (CWD), an equivalent of mad cow disease that affects deer, moose and elk, and has been spreading from west to east across the U.S. over the past three decades.

A group of researchers including Jan Novakofski, a UI professor of animal sciences, and Nohra Mateus-Pinilla, a wildlife epidemiologist with the Illinois Natural History Survey, has confirmed that the strategy implemented by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources to keep CWD in check since 2002 is working.

That strategy, employed in the eight northern Illinois counties where CWD is known to occur, combines liberalized hunting regulations (i.e., high quotas, reduced-price permits, extra hunting days) with significant culling of affected herds by sharpshooters.

“We know a lot about how far deer typically move,” said Novakofski. “If they’re sick, they’re going to spread the disease that far. So if you find a deer that’s sick, you draw that small circle and you shoot there.”

As a result of these practices, the prevalence of CWD in deer that were tested for it remained constant at about 1 percent from 2002 to 2012. For comparison, Wisconsin wildlife managers reduced their use of culling, and the prevalence of CWD among deer tested there has risen to about 5 percent since 2007.

Like mad cow disease, CWD is fatal in every animal that contracts it. Thankfully, that group has included neither humans nor agricultural animals to date.

A great big thank you this week to Diana Yates, Life Sciences Editor at the UI news bureau. Her excellent work on stories like these makes my job easy.