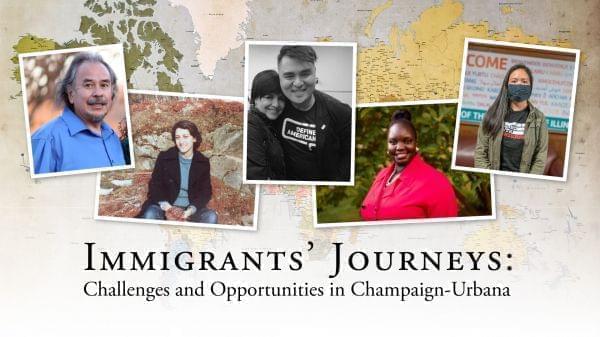

Immigrants’ Journeys: Challenges and Opportunities - Radio Documentary

Uni High, in collaboration with WILL, present the following special documentary.

Susan Ogwal

A lot of people assume that somehow because you’re an immigrant it’s as if you don’t want the same things. I want food. I want shelter. I want a good place to lay my head. I want to be able to see my children grow up and have a good life, even though I don’t have children now, but I want that for them. When you get down to the nitty gritty, if you will, the only difference is that I might come from a land that speaks a different language, or I might eat different food, or I might have different customs and things like that. But that doesn’t mean that we’re so different that we cannot relate.

Abraham Han, Narrator

That’s Susan Ogwal. She and her family fled from Uganda and came to the United States when she was seven years old. Now she is a PhD student at the University of Illinois and has lived in Champaign-Urbana for most of her life. She’s one of many who has started her life over in Central Illinois.

Gloria Yen

Champaign County is home to the largest foreign-born population in Illinois, outside of the Chicago area. So we have about one in every ten people in our community are foreign born. About one in every five in Urbana and one in eight in Champaign.

Abraham Han, Narrator

That’s Gloria Yen, director at the University YMCA’s New American Welcome Center. Champaign Urbana has a long history of supporting immigrants and refugees, especially with the rise in refugee arrivals starting from the 1960s. To understand our community, it’s important to understand its refugees and immigrants. They have a significant impact on the communities they immigrate to, and they represent larger changes and conflicts in the world beyond Champaign County. In an effort to share the stories of immigrants in our local community and explore the history and current state of immigration in the United States, University Laboratory High School students interviewed immigrants, refugees, asylum seekers, and allies in the Champaign-Urbana community. We proudly present their stories in Immigrants’ Journeys: Challenges and Opportunities in Champaign-Urbana. I’m Abraham Han.

For most immigrants, the decision to leave their homes and come to the United States is not an easy one. Many come for the promise of a better life here.

Lucia Maldonado

Things were getting really bad in Mexico. Even was I went to school and I had a good job, it was very difficult for us to make ends meet. It was really difficult to find jobs, it was really difficult. My main concern I think was safety. I was traveling from the state of Mexico, that is outside of Mexico City, to Mexico City to go to school and to go to work. So I had to travel two hours in the morning, two hours every night, to go back home. And I did that every single day. And I got robbed twice, and on the third time I was on public transportation. This person just was taking money and taking everything from everybody else in the bus. And when he got to me he just stared at my bag and I could tell that he had something, in my bag. And he said that he had a knife or a gun, I don’t remember. But I could feel that he had something. And he said, “I’m just going to take your money and don’t do anything.” And I felt really brave, I was very angry, because I had all my money from that week in my purse. So I was getting ready to turn around and confront him, and this sweet lady sitting in front of me, she just looks at me and she places her hand on top of mine, and just with her eyes she said no. So just because she did that I didn’t turn around, but I was so angry that he was just gonna take my money because I needed that money for my kids. So, I think that was the moment for me when I decided that I didn’t want to stay there because I didn’t want my kids to go through that.

Abraham Han, Narrator

That was Lucia Maldonado, who came to Champaign-Urbana from Mexico in 1996. Others come because they are fleeing poverty, political unrest and war. Here’s Carmen Loor, who came to the US in the 1980s escaping the El Salvadoran Civil War.

Carmen Loor

We often missed school, or unfortunately, our teachers, something would happen to them, and you know, we didn’t have anyone to come and teach us, because something had happened, so it wasn’t like a normal school year, for children while there is a war going on. Cause you know, one day you wake up and your friend’s gone, or your teacher’s gone Or, there wasn’t electricity, there wasn’t water. We couldn’t drive because there was too much going on.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Loor was still a teenager when her family escaped.

Carmen Loor

It was very scary. It was very scary, I remember just packing, you know, things in the luggage like clothing, and a rosary. I guess I had not spoken about this in thirty years. There was a lot of chaos, in the airport, and I just remember, getting in the plane, and there were thousands of people at the airport, just trying to get into airplanes. And there weren’t enough spaces for everyone. And I remember my city was under siege that night, the night before I was supposed to leave, and a friend called my grandmother, cause she was the one that took me to the airport. And he said, “Don’t go, because they’re burning all the cars that are going to the airport.” And I think mine was the last plane to leave the country, I can’t really remember. I was fifteen.

I mean, El Salvador was my home, it was everything I knew, but when the war came to my town, and I saw my parents suffering and losing friends, coming to the United States felt safe.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Approximately 30% of the foreign-born in Champaign-Urbana are undocumented. Because undocumented immigrants fear the potential repercussions of revealing their identities, we were not able to interview any. Instead, longtime Champaign resident Claire Szoke, who is a part of two local groups advocating for refugees and undocumented immigrants explains:

Claire Szoke

Sometimes parents or relatives, since they were fleeing from gang violence and other issues, they would pay a smuggler or so-called “coyote” to transport them across the border, and they would wind up here in Champaign-Urbana. And they do have a sponsor, somebody who they are staying with. But they have many needs. They sometimes have medical expenses. They need help with integrating in school. Urbana and Champaign are doing a pretty reasonable job. They are eligible for attending our public schools, and there are individuals there that are helping them so that is good. But, I mean, you come here as an eleven-, twelve-, fifteen-, seventeen-year-old, you are maybe not very fluent in English, if at all, and it’s a totally different culture, you maybe miss your friends back home.

Abraham Han, Narrator

As Szoke says, once immigrants have arrived here in the US, they have much work to do to adapt to their new home. Lucia Maldonado now serves as a liaison between the Urbana School District and Latino parents, helping immigrants from Central America with everything from shopping to navigating the legal system. Here’s Maldonado reminiscing about her own immigrant experience coming from Mexico to the US:

Lucia Maldonado

I didn’t know any English when I moved here. Not being able to communicate, not knowing anybody else in the community, not knowing anything about the culture and the customs, and not even knowing the community. It was very scary, it was very difficult. And I guess it’s a little bit more scary when you have kids, when you have somebody depending on you. The first time that the bus picked up my daughter I was terrified because I didn’t know how they were going to figure out where to drop her off. And she didn’t know any English and she was three years old, so I didn’t know if she was going to be able to explain. I got sick three of four months after I moved here, pretty sick actually. And not being able to communicate with doctors and having to use somebody else, to go with me, was so embarrassing. I felt so powerless over everything. Every time I wanted to go to the school to ask how my kids were going I couldn’t do it because their teachers couldn’t speak Spanish. They couldn’t communicate with me. And sometimes you find people that like really kind of make an effort to help you understand, but most people were so busy that they didn’t really take the time, so, it was, it was hard.

Abraham Han, Narrator

For new arrivals, trying to find work and a permanent home can make finding time for learning English challenging. Here’s Maldonado again:

Lucia Maldonado

Many of them come here with the idea of just getting a job and creating a better future for their kids. Most of them are families. Most of the families that we have in Urbana are families who moved here with their children when their children, or some of their children, were babies, or very young. So the adults work so much. Most of them, or many of them, have two jobs. They don’t really have a lot of time and the luxury to take days off so they can go to school and they can learn the language. I think that’s been one of the most difficult things for many of the families that we have, that they focus so much on work that they haven’t really spent a lot of time learning the language, which makes things more difficult for them. I think it’s great that in the community now, we have different groups, churches and community groups and others that are trying to open up opportunities for people to learn English. So it gives you more options to adapt your schedule so you can go learn. But it’s the same challenges. I mean, when I look at a family that just arrived last month with children, when I look at them, when I look at the whole picture, I can almost see myself twenty-something years ago. The same fears. Even when now the community is really big and they have a lot of people around them that speak the same language and can actually guide them through the process or put them in the right direction to resources, at the end of the day you go home, and it’s the same fear, and it’s the same sadness because you’re away from your country, and it’s the same challenges. And you have to deal with the fact that many of them are not going to be able to go back to their home country and getting your children adjusted to just being alone after they lived close to family members in Mexico or some other country. And here, you have to get used to everything alone.

Abraham Han, Narrator

The year before coming to the US, Urbana resident and PhD student Susan Ogwal lived in a refugee camp in Kenya. Her family had fled their home in Uganda because of a military coup. Here, Ogwal describes how she learned English after coming to the United States.

Susan Ogwal

I was very aware that I was in a new place. Some of the earliest memories I remember were noticing that we spoke English at school, and then at home, speaking in my home language. I can remember my mom taking us to the library, to learn American English through tapes. She would borrow books and buy tapes, and we would learn English that way, practice our English that way. I remember there’s a song that I’m still looking for to this day, it goes kind of something like (singing), “Do you speak English? Do you speak English? Yes, but just a little bit.” “Do you speak English? Do you speak English? Yes, but just a little bit.” So it was in those little moments that we literally learned how to speak American English. The other thing that I remember is watching TV. Sesame Street became our best friend. Not that we didn’t know the alphabet or anything like that, but it was just different, so we would always have either the news on and listening to the news, or we would always have some kind of children’s program on.

Abraham Han, Narrator

For immigrants, learning English makes it possible for them to access many community resources and to function in everyday life. Bob Kirby, who teaches English as a second language to immigrants through a program run via the First Presbyterian Church in Champaign describes:

Bob Kirby

To get a job or to do anything, almost, you’ve got to have English. I mean, without English, you can’t complete a form to open a bank account. I mean, there’s just not much you can do. I mean, you may not even know how to call 911, or how to get help. So for example, an immigrant, a person of color, being called by the police, being afraid, you know, going the other way, maybe the police says “stop,” or “hold it.” They don’t know what ‘hold it’ means, and they’re scared, and if they were home, it would mean they were going to get shot in the head if they stopped, and so they don’t, and they have a big problem.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Jobs are also a common struggle for immigrants. Here’s Alexandra Van Doren, co-founder of the local refugee support group Three Spinners, which is no longer actively operating as of 2020:

Alexandra Van Doren

There are many people that come here with very advanced degrees, that are doctors, that are experts in agriculture, things like that and their degrees don’t mean anything here as far as our system works and they have to start all over. They work in restaurants, they work cleaning houses, things like that.

Abraham Han, Narrator

The terms refugee, asylum seeker, and undocumented immigrant have been used often in the media without much attention to their distinctions. The United Nations’ definition of a refugee is someone who is fleeing conflict or persecution. An asylum seeker is a person in a similar circumstance, but whose request for sanctuary in another country has not yet been processed. An undocumented immigrant is a person who lacks the legal right to stay in the country where they reside.

Immigration is an often costly, time-consuming, and complicated process. The patchwork of immigrations laws and court rulings in recent decades have only made it more difficult. This trend, plus a perceived rise in undocumented immigration, has led to calls for immigration reform on both sides of the aisle, but no major immigration legislation has passed since the Immigration and Reform Act of 1986, which created penalties for employers who hire undocumented immigrants.

The immigration process was not always this complicated. At Ellis Island, for example, there were few restrictions on immigration, with health being the only requirement. It was a fairly simple process to get into the country, even up until a few decades ago. Ricardo Diaz, an immigrant from Mexico, recalls:

Ricardo Diaz

Things were very different than today, in that we could go back and forth, and, yes there were papers but it was not a big deal, and especially because my mom had papers, and so things moved back and forth easily.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Today, however, asylum claims typically take two years to process. While claims are under review, asylum seekers receive work permits and a Social Security Number. However, in 2016 just under half of asylum requests were approved, and the approval rate decreased to 31% in 2019. The process is complex, and some immigrants, especially children, may not have anyone to explain the intricacies of the system. Here’s Maldonado:

Lucia Maldonado

I only know one person who has been granted asylum. Unfortunately, the process is tricky. When you apply for asylum almost immediately you get a work permit and a social security number while your application is being reviewed. For a lot of these kids that don’t know much about policy and have never gone through any legal proceedings that way, I think it gives them a sense of relief and a sense of accomplishment thinking that their case is going to be approved, and that they’re not going to have to do anything else. They really take advantage of their work permit, they work a lot. But, I’m really afraid that after the two years that it takes the government to look at their applications, that some of them are going to be denied. And I don’t think they’re really understanding that. I don’t think a lot of attorneys are doing a good job explaining that. Many of them have been receiving letters already saying, “Your application is not strong enough, you need to provide more proof.” Which means that you need to keep paying an attorney because the attorney needs to be providing other ways to support that you actually need asylum. And everything is so expensive that many of them I think are trying to avoid doing it until the last very moment. But I think it’s very unfortunate that they don’t really understand the system. And even when we try, I keep pushing them and I keep asking them to talk to their attorneys and to make sure they stay on top of their applications and the communication with the attorney. Some of them do, but some others, they have their work permit already so they feel like they’re going to be okay.

Abraham Han, Narrator

With such a complicated and inefficient system, entering the country legally—whether as an asylum seeker or not—can take years or even decades. Some people may not be able to wait that long. As a result, Claire Szoke says that illegal immigration is inevitable:

Claire Szoke

There’s a lot of talk about, “Well, why don’t they come legally?” Well, it’s because it’s almost impossible for many people to come legally if you are from certain countries like Mexico or the Philippines. If you want to apply for just working in this country, you may have to wait 10 or more years before you even get on the register to apply for a permit. We both want the labor, especially the cheap labor, but we don’t want to give these individuals legal status. And I’m especially concerned with what has happened with the so-called Dreamers. These are young people who were brought here, many as infants, others as very young children. Okay, their parents came here without papers and so, of course, the children came with them, but they’ve grown up in this country. They speak fluent English. They are in all respects Americans, and yet they do not have legal status, and many of them don’t even realize this until they are in high school and they need to show a social security number so they can get a job or when they are applying to college and then they realize that, “Oops, I don’t have the documentation I need to do this legally.”

Abraham Han, Narrator

Carmen Loor, a volunteer at La Linea, which connects native Spanish speakers to local community resources, has found that the paperwork needed to gain or maintain legal immigration status is often hard or even impossible to obtain:

Carmen Loor

A lot of immigrants don’t even have their birth certificates. So you can’t come to a country where you need a work permit and to show who you are if you don’t have a birth certificate, or a license, or any of that. See, we had all of those things. We were lucky to present all of the papers that we needed. Other immigrants, didn’t even have birth certificates.

Abraham Han, Narrator

And the vetting process for immigrants, especially refugees, is substantial and lengthy. Bob Kirby has seen the challenges his ESL students face:

Bob Kirby

The process refugees go through is extensive. I don’t know how you could do any more vetting of people and checking of people than you have to go through to have refugee status here. The immigrant family, immigration and diversity immigration is still extensive. I mean it’s not—I don’t think it is as extensive as coming through the refugee program, but it’s extensive so you know we are getting the healthiest, best-checked, easiest people in the world.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Once legal status has been obtained, visas and work permits must be kept up to date. For many immigrants, the process is arduous and time-consuming, compounded by an overloaded court system. Carmen Loor saw this during her journey from El Salvador 30 years ago:

Carmen Loor

It was awful, we had to go every so often to get our work permit, we had to go every so often to show papers, my parents had to go to court to continue the case about our political asylum. It was very expensive, and we had to miss a lot of school, because, you know, you got there at six in the morning, got in line with everybody else, from all over the world, and it was four o’clock five o’clock in the afternoon and you were still there, waiting for your papers, or your work permit, or whatever, so it was very chaotic, and very expensive too.

Abraham Han, Narrator

The road to becoming a legal refugee in the United States is long, complicated, and heavily bureaucratic. Most issues relating to refugees are handled through a consortium of federal agencies and nonprofit organizations; two of the biggest include the U.S Refugee Admissions Program coordinated by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and the U.S. Refugee Resettlement Program—a partnership between DHS, the US Department of State, and the US Department of Health and Human Services. Alexandra Van Doren, co-founder of Three Spinners, explains the process for refugees fleeing their home country.

Alexandra Van Doren

It’s difficult and complicated and unfortunate. So let’s say you’re leaving Syria, you end up in a UN sponsored camp in Europe. You have to wait to be vetted and screened there, first, which sometimes they come through every six months, and if there’s some kind of weird political coup going on at that time, the UN will just not come. And then you have to wait another six months to be able to talk to somebody for step one. So, it takes literally years to get screened and vetted wherever you are first. If you have a sponsor, it’s much easier to sort of streamline getting you over here, but if you don’t, you don’t get to pick the country you go to. Whatever organizations or powers that be that are handling your case will decide based on your language skills, your occupation, your family size, things like that, where you end up. If you end up in the States, that’s another screening process that often takes up to two years. I mean, it is just background check after background check after background check. Once they get approved, then these nine voluntary organizations decide where they go and then they placed in places like Chicago or things like that. And then we get word that they are coming and where can we resettle them. So, it’s many, many steps and it is years long.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Immigrants and refugees also face significant legal challenges. Current political discourse centers on the legal process of seeking asylum, done by presenting oneself at a port of entry on the border, versus the illegal measures by which some immigrants cross the border. President Trump has advocated for tightening asylum law throughout his presidency. In January 2017, Trump signed an executive order which significantly lowered the total number of refugees and banned refugees from countries including Iran, Yemen, and Syria entirely. Its focus on countries with large Muslim populations led to some calling the order “the Muslim Ban.” After numerous legal challenges, Trump signed a more lax version of the executive order in March 2017. In July 2019, Trump signed an executive order requiring migrants to receive asylum status from the first country they pass through on their way to the US-Mexico border. All these legal actions led to a tougher road for asylum seekers in Champaign-Urbana.

Many families consist of a combination of undocumented immigrants and legal citizens. Thus, deportation can rip these families apart; most often, this means parents being forced to leave their children behind. Many local undocumented immigrants and asylum seekers must prepare their children for this possibility. Unfortunately, Lucia Maldonado sees this often in her work with the Urbana schools:

Lucia Maldonado

Many of the older kids unfortunately are getting more and more aware because their parents are making them aware, and because we are doing all this work to get ready: preparing the emergency plan, getting the guardianship letter. Part of the emergency plan unfortunately involves talking to the children. Telling them that it is a possibility, that it could happen, and teaching them what they need to do if one day they come home and mom and dad don’t show up. Or that they get a phone call from somebody saying that their parents were arrested. The kids need to know where the emergency plan is, they need to know who they need to call to get help. So they need to be involved in every process in the planning of the emergency plan. It is affecting the students because, like I mentioned before, we never really have students expressing that type of concern to their teachers or at the school. And now I can tell you that it is almost a normal occurrence. Almost every week I hear about a student being concerned.

Abraham Han, Narrator

At the state level, however, we can sometimes see a different story. Ricardo Diaz has observed these legal shifts:

Ricardo Diaz

And now for the positive, in Illinois, we have had some very progressive laws happening. We had for example, three years ago, there was permission for people to drive no matter where you came from, what your status was. As long as you could prove who you were, where you lived and that you could drive, you could get a license. And now it sounds silly, if you can show that you can drive you ought to get your license, but that didn’t happen and so we had a lot of households that did not have any drivers, they had adults that had to go to work, they had kids that had to go to school but no one could drive legally which created all kinds of messes. In Illinois, there was a law passed that they could get a license, and if they cleared their record and they had very complicated situations, people started getting licenses. So, that is a great thing. Second, we call it the Illinois DREAM Act. Kids have grown up in the U.S. and have graduated from a high school in Illinois can go to a state school and not pay foreign student tuition.

Abraham Han, Narrator

In response to President Trump’s orders restricting immigration, Illinois Governor JB Pritzker signed a series of laws in June 2019, including one that enabled undocumented college students access to state financial aid.

Visas are one avenue to legal immigration, enabling the holder to remain in the country for a set period of time, ranging from a few months to a few years. However, they can be tough to obtain and tougher to keep. There are 81 types of visas, and each has its own requirements and criteria. For most non-tourist visas, or visas that allow the holder to stay for a period of years and work while in the country, applicants must be sponsored by an employer or a family member, meaning they must already have connections in the country. Many immigrants come on temporary visas, hoping to be granted permanent residency via a green card. However, their chances are slim; in 2018, the United States issued over nine million non-immigrant visas, and only about five hundred thousand immigrant visas. But living with a visa can cause uncertainty. Gloria Yen, director at the YMCA’s New American Welcome Center, recalls her father’s experience when he emigrated to the U.S. from Taiwan:

Gloria Yen

So my dad initially came here on a student visa. He came to do a masters in mathematics at DePaul University in Chicago, Illinois. And after he graduated, he was employed on a work- based visa and he worked for maybe one or two years, and during the whole time he was trying to get his employer to sponsor him for a green card. That was a challenging process and there were times my parents didn’t know whether or not they would be able to stay and remain in the States, or if they would need to return to Taiwan.

Abraham Han, Narrator

The history of immigration in the United States displays a non-linear, but gradual acceptance of foreigners. Two major landmarks in immigration law were the Immigration Acts of 1924 and 1965. The first, in 1924, instituted a quota that limited the number of immigrants who could enter the country based on nationality. These quotas favored immigrants from Western and Northern Europe. Forty-five years later, the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 was passed, abolishing the 1924 quotas. The Act had an immediate and lasting impact on the immigration policy of the United States, in that it focused on allowing families to immigrate together, and allowed more immigrants into the country in general.

Meanwhile, our country’s current system for dealing with refugees arrived via the Refugee Act of 1980, which was passed unanimously by the Senate and signed by President Jimmy Carter in the wake of the Vietnam War. The Act raised the ceiling for the number of refugees admitted per fiscal year to 50,000 and resulted in the creation of the Office of Refugee Resettlement. More importantly, the Refugee Act provided the basis for virtually all modern American programs relating to refugees. Since 1980, the Refugee Act has evolved to meet the changing needs of the global and domestic situation. Most recently, under the Trump administration, the ceiling has been progressively lowered, and in 2018, just 22,491 refugees were admitted into the U.S.

We can’t talk about immigration today without mentioning a powerful body in the current national immigration debate: the U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement, more commonly known as ICE. Established by President George W. Bush in 2003, ICE enforces U.S. immigration laws and has the power to detain and remove illegal immigrants from the country. Some activists, like Mike Doyle, the former Executive Director of the University YMCA, criticize ICE and its actions.

Mike Doyle

There was a program started by President Bush called Secure Communities. The concept behind it was that, you know, we don’t mind immigrants being here, undocumented immigrants being here, but we really—it’s those criminals who are here that we want to get rid of, and so what we’re going to do under Secure Communities is identify the immigrant criminals, and then we’re going to ship them out of the country. So that was the idea behind it. The truth of the matter was, as happened around the country, is really that people were getting picked up, whether they had a criminal record or not, and they were being turned over to ICE and being deported. The program was a voluntary program where local sheriffs or chiefs of the police would agree that when they stop someone, and realize they weren’t a U.S. citizen, that they would take their fingerprints, and they would send them off to ICE. ICE would then run it against a database and come down and pick up people if they had a criminal record. The actual program operated where anyone who was picked up by the local police, ICE came down and took them away.

Abraham Han, Narrator

The Secure Communities program ended in 2014 due to concerns about repeated violations of the fourth amendment. It was initially replaced during the Obama administration by the Priority Enforcement Program in 2015, which focused on detaining a narrower range of undocumented immigrants. However, the Trump administration reinstated Secure Communities in 2017.

Today, the Champaign-Urbana area hosts over 20,000 immigrants with varying legal statuses. While the University of Illinois brings in highly skilled and highly educated immigrants, some people immigrate here seeking better lives, or fleeing from difficult situations, such as gang violence or political unrest. The fastest-growing local non-student immigrant populations are from Central Africa, East Africa, and Central America, while East Asians are the largest group, making up nearly 30% of the non-student immigrant population. In recent years, Champaign-Urbana has also hosted a small number of refugees and asylum-seekers from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Afghanistan, and, Iraq.

In July 2019, the Champaign City Council released a statement reassuring residents of the city’s commitment to welcoming all. In December of 2016, the Urbana City Council reaffirmed its status as a sanctuary city. This distinction was initially passed in 1986, but was adapted to respond to the recent increase in police involvement in immigration enforcement.

However, Lucia Maldonado believes that Urbana’s sanctuary city status doesn’t make much of a difference for many immigrants.

Lucia Maldonado

Most of the Latino families in Urbana live outside of the city limits. Many of them live at Ivanhoe Estates which is a mobile park area that is outside of the city. The other one is Norwood and it’s also outside of the city, so the sanctuary city doesn’t really apply to them.

Abraham Han, Narrator

As the presence of ICE has grown, so has local pushback; in June 2018, local activists held a rally to protest the ICE agents staying overnight in Champaign’s Drury Inn while conducting arrests. In June 2019, Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker signed a bill that made it illegal for law enforcement anywhere in the state to assist ICE:

JB Pritzker

We will not allow private entities to profit off of the intolerance of this president.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Several organizations have been established in Champaign-Urbana that are aimed at helping refugees and immigrants. Some were founded quite recently. Champaign-Urbana Friends and Allies of Immigrants and Refugees, or CUFAIR, focuses on helping refugees with the resettlement process, and was founded in 2016. Three Spinners, which is no longer actively operating as of 2020, provided immediate support for the basic needs of refugees, and was founded in 2015. Here’s Alexandra Van Doren, co-founder of Three Spinners, describing a family they’ve taken on to help.

Alexandra Van Doren

At the moment I know nothing about them other than there are eight people, so I assume six children and two parents, but the family make up may be different than that. And that they have been slated to come here several times and have continued to postpone because they were worried about finances. And we typically furnish their apartments. We make sure they have food at least for the first several months. And then the Refugee Center here works to make sure they are getting their documents in order and things like that. Just basic needs that we like to focus on are what we call after the fact. So once you’re here and everybody has furnished your house and gotten you settled, what do you do? How do you start finding employment? How do you find ESL classes? How do you get your kids registered in school? So, all the things that sort of happen after the big hoopla. We are really focused on assisting, so we’ll evaluate their needs. I assume it will be finding the right school for their kids. They need physicals before they start school. We gotta get them to the doctor. We gotta get car seats. We gotta get bedding for different ages of children. So, I don’t know what they will need yet, but we’re prepping.

Abraham Han, Narrator

The Refugee Center, as Van Doren briefly mentions, is an example of one of the longer standing organizations in the city. Formerly known as the Central Illinois Refugee Mutual Assistance Center, the organization has been around since 1980. Here’s Anh Ha Ho, co-director at the center, who herself was a Vietnamese refugee.

Anh Ha Ho

It’s been in operation at the local, where we are now, since January of 1982, and at the very beginning we were serving just Southeast Asians. After the Vietnam War ended, we had many families who took the boat to escape the communists and enter in refugee camps when, where we settled to come to the United States. And the founder of the refugee center was a former refugee herself. And then this is how it all started. So we were serving at the time just Vietnamese, Laotians, Cambodians, and with time more ethnicities were added. So right now, after 36 years, we have seen up to 2,000 clients unduplicated per calendar year. And right now we cover them all, from all backgrounds, all sizes, different countries, different needs.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Claire Szoke has assisted individuals from Guatemala and Honduras seeking political asylum. She gives her thoughts on the current state of immigration.

Claire Szoke

Frankly, because we do have an issue in this country. We are divided, we have a lot of rhetoric, we have a lot of what you might call myths: They take our jobs and they are costing a lot of money, and most of these can be refuted. And I think that I find it rather disturbing, some of the rhetoric.

Abraham Han, Narrator

However, amid the conflict, there has also been an increase in activism. Here’s Mike Doyle:

Mike Doyle

What’s happened that’s good, and I think reflects sort of the human spirit, is that many people have stepped up and said, “What can we do?” I think there’s a time right now where our country is raising up in a way where it’s really committing itself to the diversity of who we are. For the first four or five years that we were doing this work, people were supportive, they thought it was good to happen, but it wasn’t until the Trump administration that I saw this incredible outpouring and desire to be active. So, in some ways, it’s sort of woken up people, and engaged them more deeply.

Abraham Han, Narrator

The journey of an immigrant is often difficult, frustrating, and heartbreaking. So what exactly inspires people to become involved in the work of helping them transition? Mike Doyle describes the rewards of helping immigrants through the acclimation process.

Mike Doyle

For me, it’s seeing the joy that people have when they feel like they have control of their life. For all of us, there’s this challenge where there’s these large institutions that seem to impact our lives whether it’s the cable company, or the hospital, or the utilities, and so when people are empowered and they realize, “I’m in control of my life,” it’s a really special feeling, I think, for people, when they go from the sense of powerlessness and hopelessness to a place where they feel like they’re in control of their life again. So that for me is the joy of seeing someone’s face when that happens, when it comes to that realization.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Even though there has been a recent rise in support of immigrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers, some people in Champaign-Urbana have been involved in this work for decades. In the 1980s, the Sanctuary Movement was a direct response to the United States passing policies that made it more difficult for Central Americans to obtain asylum. The movement provided shelter and safety for the Central Americans fleeing conflict in their home countries. Churches in Champaign and Urbana also took part in this national movement.

Father Tom Royer served as pastor at Champaign’s St. Mary’s Catholic Church from 1973 to his retirement in 2011. During those decades, he’s established a strong sister relationship with the town of Calavera, El Salvador, and committed himself to international social justices issues, and advocated for Champaign-area immigrants. He describes his experiences working in a hospital where he learned from the immigrants he treated, and how those people drew him closer to the cause.

Tom Royer

What happened in ‘73, there was a coup in Chile, and so there were some refugees as a result of that military coup. And there was a family that came to Champaign, the Guijarro family, and so I became involved in the efforts to help resettle the family from Chile. And then after that, along with a couple of other Protestant ministers, we began the sanctuary program. We became involved in ministry down at the border, border ministry, down at the Mexican-U.S. border. Then the next stop for us, that we became part of a sister community relationship in El Salvador.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Beliefs, whether religious, moral, or otherwise, are a driving factor in the altruistic work that people do. Bob Kirby explains the role that his Christian faith had in his hands-on involvement with the refugee crisis.

Bob Kirby

Well, I’m a Christian and—there’s first of all the Old Testament that we believe in, that talks about the importance of welcoming the stranger, I mean it’s kinda the second most common theme in the whole Old Testament of the Bible. And then in the New Testament, we’re kinda mandated serve the vulnerable in the community, the people who most need a helping hand, so that makes it pretty easy. Someone said that the Bible is the ultimate immigration handbook, that you don’t need to know too much more about it from an attitude perspective than what’s there.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Helping immigrants can be beneficial for everyone involved. Kirby describes his work in teaching English classes for those learning it as a second language, and the things that the students taught him in turn.

Bob Kirby

Because of some other life experiences, I thought it would be nice to learn to teach people English, and my idea was to teach illiterate adults English, to help them with English, because I’ve had some experiences with people in that category. I know how difficult life can be for them if they can’t read very well or write very well, so I did some training in teaching ESL. And, volunteered in some ESL classes, where I met a lot of new immigrants and refugees for the first time, and my first one-on-one student was a man from Mexico who had some English, and had been in the States a while, but he had an amazing immigrant story, and kind of one of those stories that you talk about if you’re an American, about being responsible, and working hard, and making your way and getting ahead, and doing all those things. So he wanted some help because he wanted to open his own business. So, he was pretty high-level English, and again he and his family had already adapted pretty well. But, it was very inspiring, the things I learned from him, just from the standpoint of the things he had overcome, his motivation, what his background was and his history.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Over the years, Father Tom Royer has helped foster a connection between settlements in El Salvador, and Champaign, Illinois.

Tom Royer

I thought I would go for one time, to show up, and how do you explain this, it’s just kind of what happened. It’s a matter of the heart. Last August, I went down for my 28th trip, so something got hold of me. I remember there was a Jesuit priest who started talking about his experience. He says, “You meet the people”—and we’re talking about the suffering poor of El Salvador—“you meet the people, you fall in love, and you’re doomed.”

Abraham Han, Narrator

Celebrating the variety of perspectives that immigrants bring with them can broaden our own understanding of other cultures and enriches our own culture in turn. Father Tom Royer believes that we can discover common ground with all people and learn from them, especially the poor, humble, and sidelined.

Tom Royer

In the Old Testament, the prophet spoke of the Anawim, and that would be the broken nobodies, and when you take a look at his life, Jesus was an Anawim. He represented the unnoticed nobodies. So I think that when it comes to the people are my prophet, it is these poor people in those settlements, the dying, the sick, who I think have caught my attention and somehow have influenced me, and I’m still learning.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Many people have been inspired to help the growing number of immigrants in the community. In 2018, immigrants made up around 12% of the population of Champaign County, one of the highest percentages in the state. Here’s Gloria Yen with the New American Welcome Center.

Gloria Yen

La Línea, our community helpline, is a bilingual helpline that is run, in combination, by student volunteers that come to us from a Spanish in the Community course offered on campus, and also just Spanish-speaking community advocates in town, and so they’re able to provide interpretation and translation services, they answer and respond to calls in Spanish, and are able to direct people to healthcare resources, legal resources, housing resources, whatever they need.

Abraham Han, Narrator

These basic resources are not the only assistance immigrants may require.

Gloria Yen

One of the areas that immigrants in our community primarily need help around is with regard to affordable and accessible legal services, so we have one local legal nonprofit that concentrates on immigration that is in Champaign. They’re called The Immigration Project. Their central office is actually based out of Bloomington, and they deal with a lot of different cases from helping people get T-visas and U-visas, which are for victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, and trafficking, to helping people petition for green cards and for family members to come over, to applying for citizenship, things like that.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Yen and a colleague from the New American Welcome center have since spent over 500 hours to become a legal immigration representative recognized by the U.S. Department of Justice, and has been giving legal advice to those who call. Mike Doyle has noticed an overall growing sense of community amongst immigration advocates, especially thanks to the University YMCA, which helped a group of students found the CU Immigration Forum several years ago. These students spent a summer talking with people who work with local immigrants.

Mike Doyle

One of the things that struck them is, Gee, there’s all these people doing work with immigrants but they often don’t know each other, aren’t aware of the work that each other’s doing. So they brought those folks together and just said let’s have a forum where we can start sharing and meeting on a monthly basis. Out of that grew CU Immigration Forum. So I think in some ways the Y helped to begin that consolidation of effort in the community, really bringing them together and sort of combining their efforts.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Communities like the one Mike Doyle describes create opportunities for the members to learn from one another and gain new perspectives. Here’s Gloria Yen talking about one realization she had.

Gloria Yen

I know that social studies wise, when I was in elementary school and middle school, a lot of the teaching emphasized kind of the melting pot of the American experience with a lot of different immigrants coming in and blending their cultures together. I think that what I’ve come to appreciate over the past several years is taking time to better appreciate the richness, diversity, and kind of unique perspectives that each culture brings to the table. It doesn’t have to be a melting pot, not everything has to be mixed and blended together. People can preserve their national identities and cultural selves without having to necessarily assimilate to what people perceive as the model American citizen.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Even as immigrant communities strengthen, many residents see the current political climate as deeply harmful to both individuals and communities. Lucia Maldonado recalls seeing visible changes in the environment at Urbana High School, where she serves as a liaison between the school and Latino parents.

Lucia Maldonado

It’s very clear to us how bad this political climate is affecting everybody, but especially immigrants. We have students coming into the school, talking to teachers and talking to social workers about their fears of deportation or their fears for their parents being picked up by immigration. That didn’t happen before. Things are very different and we see that with adults and we see that with children too, which is very unfortunate that kids should be able to focus on their school work and on their learning and instead, part of their mind is always focused on fear.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Mike Doyle recalls a specific incident which ignited local activism.

Mike Doyle

There was a particular case of a woman who was here, she was undocumented, she was a single parent, had three kids here. It was a Saturday, and she was going to pick up her son, who was at soccer practice, and she got in a little fender bender. No big damage, but the person she had the fender bender with was a local police officer. When she took out her driver’s license to exchange information with him, he saw that it was a Mexican ID she had. He called the police, the police came, they took her off to jail, and locked her up. Her child sat at soccer practice not knowing what happened to her. The child’s coach had to take care of the child, to get him to relatives. She sat in the county jail, from—this was a Saturday, she did not get out of there until Wednesday, and it was only after members of CU Immigration Forum went to the sheriff and said, “You can’t hold her more than 48 hours, even under this program; you’re violating the law,” and actually pressured him to release her. She had no criminal record whatsoever. That case, because it was so powerful, really mobilized the community around, “This isn’t the way the program was supposed to work.”

Abraham Han, Narrator

The situation led to a meeting with the sheriff.

Mike Doyle

Often times people with power don’t respond right away, so you have to do something to get their attention. That’s where something like a protest, or a big meeting, in the case with the sheriff, we invited him to a forum, and it was at the Champaign Library, and there were probably 150 to 200 people there. I think it opened his eyes. It wasn’t rowdy, but he was shocked at how many people cared about it.

Abraham Han, Narrator

The sheriff in Mike Doyle’s story saw a different perspective when he came to the forum. Father Tom Royer believes that that sort of communication is necessary to open people’s minds. He finds that oftentimes, people don’t understand the reasons why an immigrant may come to America, and how decisions made in the United States affect communities like the one in El Salvador that he visits for relief and ministry.

Tom Royer

They don’t want to leave their home, but they’re here because of necessity. And if you want to take a look at why are they here, you can never ignore the influence of the empire. The empire that has a lot to do with the politics, and with the economy and every other way, and that is the US. I think some of the very serious causes of bombings and military sweeps that are going on in my mountain community are based on decisions made in this country. Why did you have the massacre of El Mozote, which is about as the crow flies about 10 miles from my community? That was because politics in this country. The biggest massacre in El Salvador in December of 1981, that was because a president decided that we needed to deal with the communist threat south of the border. Those are life or death decisions being made by the political system in this country and it just, it—well anyways, it’s very very sad. We need to have a better educated public in this country about some of these very important issues. It’s about the people there for God’s sakes. What do you think people should know about the immigrant? That they’re people!

Abraham Han, Narrator

Over the years, as more immigrants have come to the United States, Susan Ogwal has seen the African community grow in the Champaign-Urbana area.

Susan Ogwal

By the time my dad graduated we had what we called an Orchards Down community. It wasn’t very big, as it is now. Now we have hundreds and hundreds of families that are here from the continent, and they range from anywhere from Nigeria, to Kenya, to Cameroon, from Congo, DRC, Zambia, Senegal, Sudan, so there’s a much, much bigger variety than I’ve seen in the last 20 plus years that I’ve been here. You get to meet like-minded individuals, or a least folks who you know understand some of the customs, and some of the traditions, or understand some of the ways of how you grew up, because they also grew up like that as well.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Anh Ha Ho, who is co-director of The Refugee Center, describes another benefit that immigrant communities offer: mutual assistance.

Anh Ha Ho

The Vietnamese community is just a Vietnamese community, and because I am Vietnamese myself, I have to admit that we provide a lot of help. My husband sees a patient at home all the time, he also is part of a free clinic. So, whoever is need of medical attention either will come to our home or will go to the free clinic. And because I have gone through their situation before, so I know what it takes, I know what they have to do in order to find roots here. I always tell my clients, “It doesn’t matter, we all have a story to tell. But just remember one thing, each story has to show some truth. So, take the good of this country, keep the good of our culture, but do not try to become someone you are not.”

Abraham Han, Narrator

To Mike Doyle, part of making the most of what you have is realizing the power one has to make a difference.

Mike Doyle

There’s lots of things people can do. So, you know, you can support your favorite nonprofit, if it’s working on this stuff. You can also volunteer. I think that people need to appreciate that this work doesn’t happen unless people give of themselves, so that’s as important as giving money. And then I think it’s really getting engaged. Apathy is this thing that we all feel on some level, that people are tired, they work hard, some people have multiple jobs, it’s hard to care about it. And what motivates us is when we realize that making that extra effort will make a difference. Hopefully people will recognize that by getting engaged, they can really change the world.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Claire Szoke believes that people today have the chance to learn about refugees at a deeper level than before. After all, there’s a difference between hearing about refugees in the news, and becoming friends with one.

Claire Szoke

I think one of the main benefits in the sanctuary movement and these other movements that have been part of the Champaign-Urbana community for many years has simply been that people get to know immigrants, refugees on a one-to-one personal basis and find out that they have the same hopes and dreams as we do. It’s one thing to help them with the material need, it may be just as important to play basketball with them or invite them over for a family dinner.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Immigration organizations are striving to spread this key message to both immigrants and non-immigrants alike, as they work to help immigrants settle into their new lives in the United States of America.

Immigration, as you have probably realized by now, is a nuanced topic, to say the least. If you are curious about the role you can play in the lives of immigrants in central Illinois, local organizations are a great way to learn more. CUFAIR helps immigrants establish a place in America by helping them find jobs and homes, for example. La Linea, a program of the University of Illinois YMCA, provides resources ranging from childcare to legal assistance. The Refugee Center, is known for the range of services is provides to immigrants, including translation, counseling, and legal assistance. You can go to our website for direct links to these organizations’ websites, as well as further information and resources about immigration.

And finally, here’s Father Tom Royer with one more piece of advice.

Royer

Listen from the heart to the stories of the people who struggle. Listen with your heart to their stories, and their stories are just like our own, but their experience, where they come from, is something that is so foreign to us, we simply do not understand unless we are listening to their stories. Their stories are very very important.

Abraham Han, Narrator

Since the recording of these interviews in 2018, a lot has happened. Some of it has been difficult news for immigrants and immigrant advocates. The Supreme Court allowed a version of the travel ban commonly known as the Muslim Ban to stand on June 26th of 2018.

A record 35-day government shutdown began in December of 2019 because Congress refused to give Trump the funding he wanted for the Mexico border wall. In June of 2020, in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, Trump instituted visa suspensions that would go until the end of the year. The Migration Policy Institute estimates that 167,000 workers and their dependents would be blocked between July 1 and Dec. 31.

There are still some bright spots. On June 18 of 2020, the Supreme Court blocked the Trump administration’s efforts to dismantle DACA. And work has continued locally as well. For example, in 2019, the University YMCA’s New American Welcome Center was accredited by the Department of Justice to provide immigrants with legal representation. Gloria Yen, who you heard in this documentary, is one of these legal representatives. Three Spinners has dissolved, but Champaign-Urbana’s local organizations have continued to support immigrants and help them stay aware of any legal developments, even during the pandemic. One great example is the Immigration Project, which distributed $20,000 in cash assistance to immigrant families who did not receive federal COVID-19 relief payments in May.

The new Biden administration, inaugurated in January 2021, is a strong contrast to the previous administration in terms of attitudes to immigration, and activists are hopeful that policies will improve.

We bring our final update with a heavy heart. During the making of this documentary, Claire Szoke died from complications related to Covid. We send our warmest condolences to her family, and we are honored and grateful to have met her.

Though much has changed over the years, the work of immigrant advocates has persevered with the same spirit that you heard in this documentary.

I’m Abraham Han. Thank you for listening to Immigrants’ Journeys: Challenges and Opportunities in Champaign-Urbana.

The program was produced by myself, Abraham Han, Annette Lee, and Nathalie Stein, with special help from Lawrence Taritsa and Edward Kong, as well as additional help from Pomona Carrington-Hoekstra, Noel Chi, Danbi Choi, Solomia Dzhaman, Keshav Gandhi, Sarah Hashash, Zona Hrnjak, Collin Jung, Allie Kim, Anika Kimme, Emi Loucks, Betty Nguyen, Anna Ondrejckova, Elijah Song, Zhaohan Sun, Maggie Tewksbury, and Jonathan Yu.

Interviews were conducted by the Uni High class of 2022 and members of the Uni High Oral History team.

Stories were contributed by Ricardo Diaz, Mike Doyle, Anh Ha Ho, Bob Kirby, Carmen Loor, Lucia Maldonado, Ben Mueller, Susan Ogwal, Tom Royer, Claire Szoke, Alexandra Van Doren, and Gloria Yen.

The program was directed by University Laboratory High School teacher Melissa Schoeplein, with technical support from Jason Croft and Steve Morck, marketing support from Liz Murray and Samantha Shrage, and Kimberlie Kranich for editorial support.

Uni High, in collaboration with WILL, present the following special documentary:

Immigrants’ Journeys: Challenges and Opportunities in Champaign-Urbana explores individual immigrants’ journeys to central Illinois as well as the journeys of people who came to be vocal advocates for immigrants’ rights.

The project features the stories of Champaign-Urbana residents Lucia Maldonado and Ricardo Diaz from Mexico, Carmen Loor from El Salvador, Gloria Yen, whose father came from Taiwan, Susan Ogwal from Uganda, Anh Ha Ho from Vietnam, Faranak Miraftab from Iran, and Prosper Panumpabi from the Democratic Republic of Congo. Advocates' stories from Mike Doyle, Bob Kirby, Ben Mueller, Father Tom Royer, Claire Szoke, Alexandra Van Doren, Ann Abbott and Gloria Yen.

Through these stories, listeners will better understand why people immigrate, the hardships and opportunities they may encounter in the process, and the transformative power of human connection beyond borders. These experiences can help us better understand the past and present of Champaign County, as well as its connection to large changes and conflicts in the wider world.

Links:

- The Refugee Center

- The New American Welcome Center

- Project Welcome

- Immigrant Services of Champaign-Urbana

- La Colectiva

- The Immigration Law Society - UIUC

- ESL at the First Presbyterian Church of Champaign

- CU Immigration Forum

- Illinois Welcoming Center

- The Immigration Project

- Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights

- US Office of Refugee Resettlement

- UN Refugee Agency

- US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants