Rebuilding Foundations, Part Two

“Rebuilding Foundations: Housing and Hope in the Mississippi Delta,” the first part of the Uni students' documentary, traces the history of the need for decent housing in the region due to racial inequities created through sharecropping, the mechanization of farming, inadequate public education and residential segregation. The documentary explores the creation of Habitat for Humanity, the founding of the first Habitat affiliate in the Mississippi Delta in the mid-1980s, and the beginnings of the "Collegiate Challenge" initiative in the 1990s.

By hearing the perspectives of homeowners, Habitat staff and community leaders, we get a sense for how important Habitat has been to the well-being of families and children and the vitality of many communities. By listening also to stories of volunteers from Illinois who found new meaning and direction for their own lives, we come to understand the mutual benefits of community development initiatives that bridge racial, socioeconomic, religious, generational and regional divides.

Uni High alumnae Maggie Tweksbury (L) and Mallika Luther (R) working with former Uni teacher Bill Sutton on the installation of a roof on a house that, for several months, had been without one. The project was finished in record time. (photo by Janet Morford)

Under the guidance of teachers Janet Morford and Bill Sutton, Uni High students began this project in July 2015. Conducting oral history interviews for the first time “in the field” (outside of the WILL recording studios), Uni students recorded 20 in-depth interviews with long-time residents of Coahoma and Tallahatchie Counties in Mississippi, as well as 16 interviews with people who live in central Illinois but have worked with community development organizations in the Delta. They gathered testimonies from Habitat homeowners, construction specialists, affiliate coordinators, volunteers, leaders of churches and other local organizations.

Uni alumna Kathyrn Dullerud listens to Mississippi resident Dorothy Jenkins explain how the need for affordable housing in the Delta stems from the history of economic exploitation in the region.

Some interviewees explained how the practices of sharecropping contributed to the dire need for decent housing in the Delta. Historically, landowners had provided simple shacks for workers to live in close to the fields. When agriculture was mechanized, wages increased slightly but landowners employed fewer field hands and felt no need to invest in their housing. As Dorothy Jenkins of Sherard, Mississippi recalls, "After wages had gone up and machinery was taking over, farmers were not providing decent houses for people to stay in. You could stay wherever you want to, at your own risk. If the house had a top on it, all well and good. They were not going to put out any money to fix it." Faced with an inadequate local stock of housing, community leaders such as Dorothy Jenkins came to see Habitat for Humanity as a way to "bring dignity" to the lives of people around them.

Other interviewees underscored the fact that Habitat for Humanity enabled blacks and whites to get to know each other by working side by side. Pastor James Jackson, who grew up in Mississippi and works with youth at risk in Clarksdale, put it this way: "Every time Habitat came or you guys came down from Urbana (...) I thought it was really neat that I see a group of whites (...) coming down in a black neighborhood -- and it kept reaffirming to me that the past is the past. We got whites that really care. (...) We had so many whites that got involved, that kinda motivated [me]: 'I like this. I can work with this.' ”

Bill Sutton (Uni teacher), Keisha Patel, Rima Rebei, Katie Tender, Maggie Tewksbury Middle row: Ha-il Son, Zina Dolan, Iulianna Taritsa, Carissa Hwu Back row: Even Dankowicz, Andrew Stelzer, Janet Morford (Uni teacher) and Ellen Rispoli

Bill Sutton, who retired from Uni High in May 2017, also stressed the mutually beneficial nature of the connections forged over time with people in Mississippi: "Working with the people connected to the Habitat affiliates in the Delta has been THE most enriching aspect of my life (...) Much of that enrichment has come from being exposed to the incredible graciousness of the communities being served. But another major aspect has come from watching my students — over 400 in the 21 years Uni has partnered with Delta affiliates -- also come alive in this process. What excites the students is that they can come to see their own potential through a non-academic, non-privileged lens. In this work, they gain exposure to experiential realities of trust and reconciliation otherwise closed to them, and they respond enthusiastically (even joyfully) to these opportunities to participate in positive change."

Uni alumna Ellen Rispoli is one such student. After participating in the interview teams in both Illinois and Mississippi, she observed: "Before going to the Delta, to serve, to listen, and to love all had three different meanings. But the people I met showed me that they're all the same."

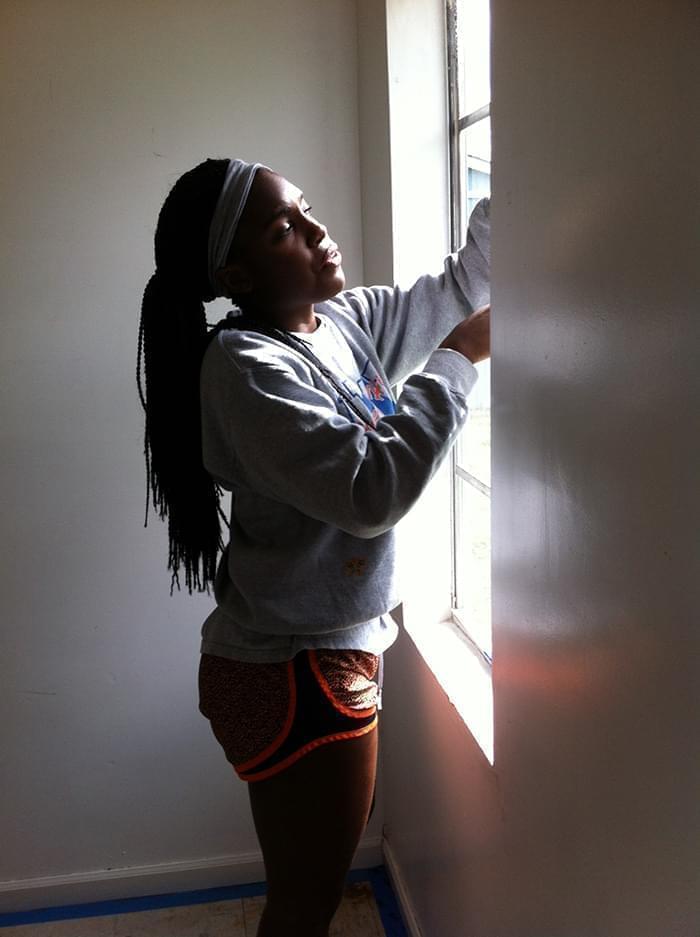

Aja Trask, who first went to Clarksdale with Habitat work trips organized by Uni teachers, works on a Habitat renovation project. Like other Uni alumni before her, Trask chose to delay her entry to college in order to work as an intern with Spring Initiative. (photo by Janet Morford)

The second part of the documentary, “Rebuilding Foundations: Community and Change in the Mississippi Delta,” explores what led a stream of well educated young people from east-central Illinois to return to the Delta, starting in the late 1990s, in order to work on a longer term basis. It features the perspectives of long-time Mississippi residents and of outsiders who have chosen to settle there, expanding the focus from the issue of affordable housing to concerns over educational opportunities and generational poverty. This part of the story also shows how the programs first implemented at Uni High have spread to other central Illinois public high schools, including Urbana High School and Paxton-Buckley-Loda High School, reinforcing, deepening and diversifying the connections between people and organizations in Illinois and in Mississippi.

According to Mark Foley, history teacher at Urbana High School, “One of the things we’ve really taken from the trip, I think, is that a lot of the way that we do school probably needs to change. It’s really not okay that we have to drag kids 8 hours away and put them in a dorm together for a week to get more authentic learning.” His colleague Laura Koritz adds, “When I talk to my students, I feel like… they don’t have the opportunities to connect with each other as much as would be meaningful for them. (...) What we do in Mississippi would be good for all students.”

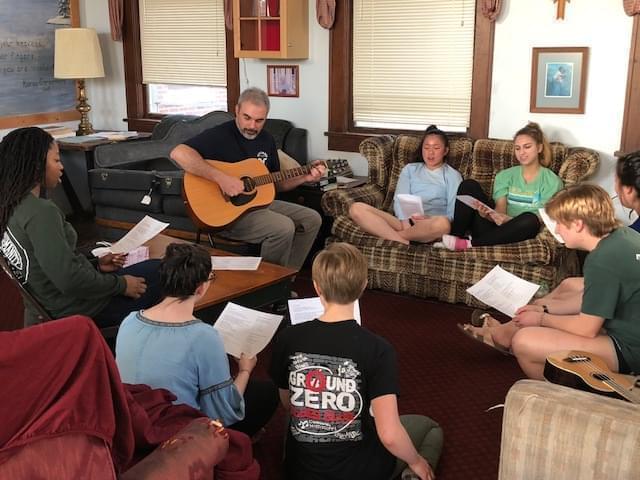

Uni High and Urbana High students sing civil rights songs with Urbana High history teacher Mark Foley. Habitat groups from both schools were working in the Delta in February 2018. (photo by Janet Morford)

For Jason Peterson, teacher at PBL High School, taking students to the Mississippi Delta is valuable in part because it leads them to question the assumptions surrounding their own lives. As Peterson explains, “Even if the sharecropping system isn’t around anymore, the privilege and the legacy of a racialized hierarchy is still being passed down…. That is the thing that is hardest for the students to understand. It’s easy to say like, slavery’s bad, (...) to say, “Well, why don’t these people just choose to get a better job or make money?” (...) I think it’s important for students to learn through this trip that none of those people are choosing to be poor. Generational poverty -- it’s an incredibly difficult thing to work your way out of.”

Simply meeting people involved in community development and listening to their stories was an eye-opening experience for many students. Maggie Tewksbury is a recent Uni graduate who conducted multiple interviews in the Delta, while also serving as a volunteer for Habitat and other community organizations. Listening to people's stories helped her grasp what she called "the unfair, and yet ingrained, inequalities in our society that affect all of us in ways that I had not previously understood."

Clarksdale resident Byron Bays talks with Uni alumna Stella Faux about the music classes offered at Griot Arts, one of the local non-profits working to enhance opportunities for youth at risk. (photo by Janet Morford)

Uni alumna Stella Faux has also made multiple trips to the Delta, both to conduct interviews and to volunteer with Habitat and with Griot, a local arts enrichment organization. Participating in this project made it necessary, as Stella put it, "to stare things like white supremacy and enduring racism and inequality in the face, as well as to acknowledge that systems of oppression are rooted in the history of this country. However, the story of Habitat in Clarksdale also sends a message of solidarity and hope in the face of obstacles.”

Veronica Kahaleua is a native of Clarksdale who attests to the difference made by Habitat and other non-profit organizations that have taken root in the Delta. As a Habitat homeowner, a staff member of the non-profit Spring Initiative, and a friend to many of the outsiders who have come to work in the Delta, Kahaleua observes, “Had I not been with Habitat in all this, I would not know about … all of these positive things that are going on, all of these people that are being helped from them coming back and forth [from Illinois to Mississippi], from all these years bringing kids, bringing family, bringing people down here to do what they do: connecting them and just showing them love. (...) I’m proud to be a part of something that I know works.”

Taken together, the stories that the Uni students collected enabled them to tell a larger story: one that is rooted in the historical legacy of slavery, sharecropping and Jim Crow, but that begins a new chapter in the 1980s, leading to racial reconciliation, stronger communities, and greater opportunities for many. It is a story about significant change in people’s lives -- the renewed faith and sense of purpose that volunteers from Illinois gained by working in the Delta as well as the hope and dignity that people burdened by generational poverty experienced through the work of Habitat for Humanity and other community development organizations.

Uni Students reviewing their work at the end of a long day.

Yet conducting and transcribing over 35 interviews was only the beginning of the process. Led by senior student producers Carissa Hwu, Annemarie Michael, Andrew Stelzer, Stella Faux and teacher Janet Morford, a team of Uni students then devoted countless hours to selecting and editing interview segments and background music, writing, revising and voicing the script, and bringing these pieces together in an audio documentary. Learning to produce a coherent documentary using this material was in itself a valuable experience. As Andrew Stelzer recalls, the students had to "learn how to adapt quickly and improvise on this project, picking up new skills as needed to get the job done. We also learned a lot about teamwork and the amount of effort and organization it takes to complete a project of this scale." At the end of the three-year process, Andrew observed, “This documentary isn’t perfect. But I’m so proud of all the time and effort everyone put into making it the best we could, and I think that the end product is truly compelling. This project has certainly changed my life, and I hope that it has had and will have a positive impact on many other people as well.”

Jason Croft, Production Manager at Illinois Public Media, coached the novice producers as they neared the end of the two-year process. “The level of seriousness and professionalism these students brought to the project was amazing,” said Croft. “They were willing to put in the extra time—nights and weekends—to make sure this documentary sounded right. They should be proud of what they accomplished.”