So You Think You Know The Magna Carta…?

John's seal on the cover of Magna Carta: The Birth Of Liberty Viking Press

This year, the Magna Carta will turn 800 years old. The document, literally “Great Charter” when translated from Latin, is revered as the founding document of western democracy. Its language is found in many later key political documents including the US constitution and the Bill of Rights.

But when historian Dan Jones dug into its history he found a very different story than we assume.

The Magna Carta ought to be dead, defunct, and of interest only to serious scholars of the thirteenth century.Dan Jones

“Eight hundred years after it was first granted beneath the trees of Runnymede … the Magna Carta is more famous than ever. This is strange … The Magna Carta ought to be dead, defunct, and of interest only to serious scholars of the thirteenth century.”

So writes Jones in the introduction of his newest book, Magna Carta: The Birth of Liberty. Jones is a historian and author specializing in the United Kingdom’s Medieval History.

Dan Jones

“It was a peace treaty. Very simply it was a peace treaty between King John on the one side and his barons who had rebelled against him on the other side,” said Jones.

He further writes in his book's introduction that “for the most part the Magna Carta is dry, technical, difficult to decipher, and constitutionally obsolete. Those parts that are still frequently quoted … did not mean in 1215 what we often wish they would mean today. They are part of a document drawn up not to defend in perpetuity the interest of national citizens but rather to pin down a king who had been greatly vexing a small number of his wealthy and violent subjects.”

To understand how the Magna Carta went from the peace treaty granted at Runnymede that Summer day in 1215 (but never enforced) to a symbol of western democracy, we need to spend more time, as Jones does in his book, in the Medieval United Kingdom that produced it.

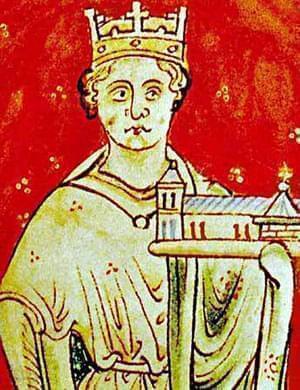

Portrait of King John of England (John Lackland) by Matthew Paris from his Historia Anglorum 1250-59. British Library Royal MS 14 C.VII, f.9

The United Kingdom of feudal times, was, on one level, run by barons, who were essentially "mini-kings." They had great power and great wealth and generally had the freedom to run their estates as they pleased. King John, however, a member of the Plantagenet dynasty, was the ultimate power in the land.

In addition, he was an incredibly brutal king who continued a tradition set by his father and brother (Richard the Lionheart) of high taxes to fund vastly expensive foreign wars, and an incredibly firm hand when dispensing justice. John's barons found these, among other practices, increasingly vexing. Several banded together, and around Easter 1215, revoked their oaths of loyalty and rebelled against their king.

“If you crossed King John, at this time, the consequences were absolutely dreadful for you so … the people who stood up against John were showing quite a bit of bravery,” said Jones.

They also had luck.

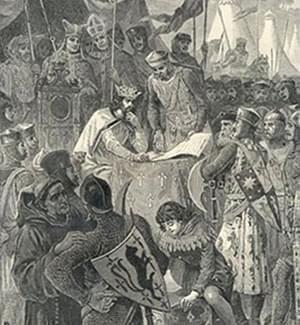

King John grants the Magna Carta in a scan from Cassell's History of England - Century Edition. The book was published circa 1902.

As their uprising began to look bleak they, with the help of the London merchant class were able to seize London – cutting off John’s access to his garrison and, more importantly, his treasury. John had no choice but to negotiate.

In mid-June 1215, the Magna Carta was granted at Runnymede and “well, almost the first thing John did was to write to the pope, who in feudal terms was his overlord. He wrote to Pope Innocent III and said ‘I need to get out of this charter.’ The pope wrote back, dutifully said, anyone who obeys the Magna Carta will be excommunicated, they will rot in hell for all eternity,” said Jones. “So the Magna Carta collapsed and a civil war broke out.”

That should have been the end of the Magna Carta.

But then King John died.

Foul as it is, Hell itself is defiled by the presence of John.Matthew Paris, Chronicler, 13th Century

When John died he left behind a son, Henry III, as well as a Kingdom in chaos and a second contender for the throne.

Henry III and his men were able to win the throne “because of a really quite extraordinarily prescient and intelligent decision … which was to re-issue Magna Carta. Not as a peace treaty foisted on an unwilling king, but as something that was put out there by the new government as a show of commitment to reform, a show of commitment to government according to the principles of the rule of law,” said Jones.

It worked.

“Little by little the Plantagenet crown began to recover,” said Jones. “And they did so by re-issuing Magna Carta: 1216, 1217, 1225, and then thereafter at every moment in political crisis in the thirteenth century people would look to Magna Carta, demand Magna Carta.”

With each re-issue the myth of the Magna Carta began to grow. “By the end of the 1300th century, Magna Carta was kind of a symbol a myth, a legend,” said Jones.

The legend of the Magna Carta is perhaps well illustrated by its current loan to China. A 1217 copy of the Magna Carta was loaned to China recently to be put on display for students at the University of Beijing, but instead the document is being kept inside the ambassador's house.

“There’s clearly some feeling among the Chinese authority that this truncated, Latin, Medieval charter, which I’m sure very, very few people would be able read, in China or indeed anywhere else, might somehow be dangerous and that the ideas in Magna Carta might not be the sort of thing they want in young Chinese students minds. Well, that tells us quite a lot about the enduring worldwide symbolism of the Magna Carta,” said Jones.

When you look at some of the issues that surrounded and led to the Magna Carta, Jones says, they feel familiar. “They weren’t new in 1215 and they aren’t new today.”

“One of the purposes of reading history is to illuminate the context of our own times and give us examples, give us context, give us wisdom that will help us navigate the waters that we sail through today.”