Farming Is Headed Toward A Gene-Editing Revolution, And Hoping The Public Comes Along, Too

Professor Patrick Tranel points to male (right) and female (left) waterhemp plants in a greenhouse at the University of Illinois. To help control the species, he's trying to identify genes that determine the sex of the plant. Madelyn Beck / Harvest Public Media

Sci-fi writers have long warned about the dangers of modifying organisms. They come in forms ranging from accidentally creating a plague of killer locusts (1957) to recreating dinosaurs with added frog genes (2015). Now, with researchers looking to even more advanced gene-editing technology to protect crops, they’ll have to think about how to present that tech to a long-skeptical public.

Stephen Moose is a professor and researcher at the University of Illinois. He's generally focused on corn, biotechnology and plant genetics.

Now, with researchers looking to even more advanced gene-editing technology to protect crops, they’ll have to think about how to present that tech to a long-skeptical public.

“If you put something out where the public isn’t comfortable with it, it doesn’t matter what the science says,” said Stephen Moose, a professor of maize, breeding and genetics at the University of Illinois.

Consider the revolt against genetically modified food. Moose said the fear of genetically modified organisms, or GMOs, might have been avoided if the public had been let into decision-making processes from the beginning. He said the new technology is no different.

CRISPR, for example, is already making it easier to edit genes. There’s also testing going on with something called gene drive. Moose said the goal is to “alter the outcome of inheritance” (aka the traits, like brown hair and green eyes, that get passed on to new generations).

“There are rules, and you can, if you understand how that process works, you can make it violate the rules,” he said. For example, imagine researchers edit a mosquito gene so that it’s born with a trait that handicaps it or kills it. Usually, the lucky few mosquitoes born without that trait would survive longer and take over. That’s evolution. With gene drive, 100% of offspring could get the negative trait, eventually killing the population. “It basically creates a dead end, you know, (a) genetic dead end,” Moose said.

Driving science forward

Gene drive is likely decades away from regulatory approval, but researchers are making baby steps with things like with waterhemp and Palmer amaranth —some of the nastiest weeds plaguing Midwest farmers.

Patrick Tranel, a University of Illinois crop sciences professor, is looking into using gene drives on those weeds to help overcome herbicide-resistance, reduce the need for herbicides like Roundup and dicamba and help farmers produce more food for a growing world.

In a recently published article in Weed Science, Tranel showed how he made progress towards finding key sex genes that he’d need to edit to successfully use gene drive. However, that doesn’t mean gene-drive modified plants will be in the field tomorrow.

“First we need to find the genes. And then we have to alter the genes in order to actually make a commercial weed control strategy,” he said.

Patrick Tranel is leading research on some of the nastiest weeds Midwest farmers come up against: waterhemp and Palmer amaranth.

Plus, any approved gene drive will likely require some sort of fail-safe or kill switch to make sure it doesn’t wipe out a species. It’s something many researchers are already looking into.

“It's not our goal to eradicate water hemp from the face of the earth,” he said. “Nobody wants to do that, even though it's a weed.”

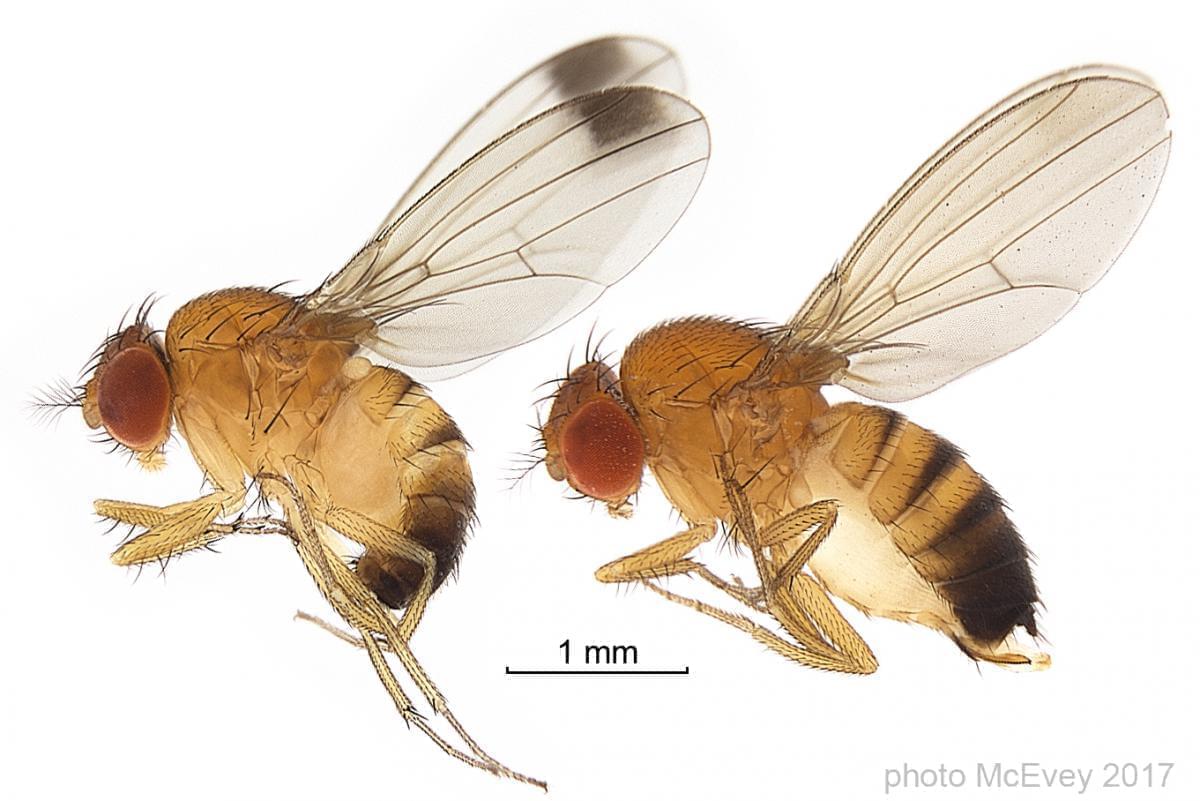

Another scientist — University of California, San Diego, assistant professor Omar Akbari — is working on controlling agriculture pests with gene drive, but isn’t focusing on weeds. He’s going after an invasive fly that sounds like (and somewhat acts like) a Star Trek villain: Drosophila suzukii.

“Females have a serrated ovipositor. Essentially, it's like a knife that is on their posterior end, and it enables them to stab the fruit with this knife and inject their eggs into the fruit,” he said.

The larvae hatch inside the fruit, eating it from the inside out. And the fruit-buffered eggs are hard to kill.

“Prior to the introduction of this invasive pest, the California Cherry Board, or (cherry) industry, was actually not using insecticides. The cherries were essentially organic. But since the introduction of this one past, now, they use up to four different kinds of insecticides multiple times during a season,” Akbari said.

Drosophila suzukii, or the spotted wing drosophila, is an invasive fly species that's wreaked havoc on fruits and berries around the U.S. The female (right) has a "serrated ovipositor" on her rear end to stab into fruit and inject her eggs.

Akbari said researchers are looking at other ways to handicap the fly beyond gene drive, though, like releasing CRISPR-sterilized males into the population in an effort to get “safe and controllable” technology into the fields sooner.

Still, Akbari, Tranel and Moose agree: The public needs to come along on these early steps if gene drive can ever be used in the field. They’re not even asking for full support. They just want the public to make knowledgeable decisions based on costs and benefits.

And of course, no one scientist wants to be personally responsible for unleashing a dystopian plague, like giant, man-eating bugs, onto the Earth. Follow Madelyn on Twitter @MadelynBeck8