Forty-Five Years Ago, We First Landed On The Moon

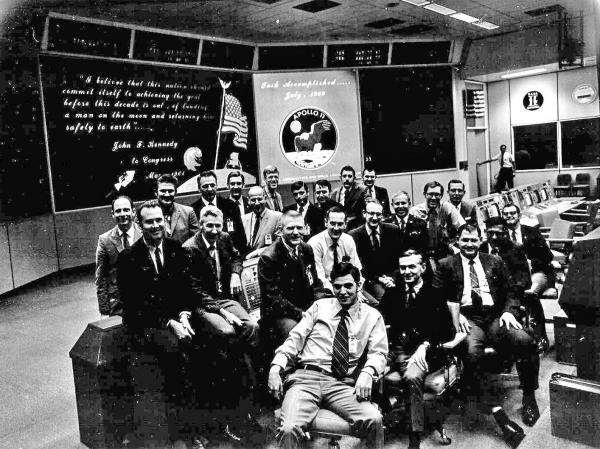

Forty-five years ago this Sunday, Apollo 11 became the first space flight to land men on the moon. At Mission Control in Houston, Gene Kranz was the man in charge.

Kranz spent more than three decades working for the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, serving as flight director for both the Gemini and Apollo space programs.

He is probably best known for his role leading the Mission Control team that brought the crew of the ill-fated Apollo 13 lunar mission safely back to earth. That mission was later depicted in the movie "Apollo 13," in which Ed Harris played the role of Kranz.

Now 80 years old, the real Gene Kranz was in town recently to speak at his alma mater, Saint Louis University's Parks College of Engineering, Aviation and Technology. He also talked to middle school students at the Saint Louis Science Center.

During Kranz’s return to St. Louis, Véronique LaCapra sat down with him to ask about his early life, his long career with NASA, and his role in that historic first lunar landing.

VL: Outside of science fiction, there was no space program when you were a child. Did you ever imagine that one day you might be involved in sending rockets with humans on board to the moon?

GK: No, actually space was not in my game plan, it didn't exist at that time. I was a pilot. That’s all I wanted to do. And I was real happy in the job.

I was flying on the station in Formosa for a while, and I landed an aircraft in October ’57. My crew chief ran up and said, 'You know, Russians have launched a Sputnik.' And I said, 'Well what’s a Sputnik?' He said, 'Well, they have a little satellite going around the Earth.' I said, 'Oh, that’s pretty neat.' And then I went back to worrying about flying.

VL: Now you’re not quite telling me the truth, because I happen to know you wrote a thesis in high school that had something to do with going to the moon.

GK: I was a reader of pulp fiction. I read virtually all of the early accounts of life outside the Earth’s atmosphere, and I looked for a senior thesis that was somewhat different, and something I felt reasonably comfortable with and familiar with. And I thought, 'Gee, that would be neat.'

My thesis title was, 'Design and Possibilities of an Interplanetary Rocket to the Moon.' The only problem I had, I got him to the moon, but I couldn’t figure out a way to get him back. So I left him there!

GK: It was really a challenge because I knew very little about my father. We lived in the south end of Toledo, Ohio. But as soon as he died, my mother wanted to get us away from the wrong side of the tracks. She wanted us to go out to West Toledo. And somewhere or another she found the money to obtain a house out there, make a down payment on a house.

And she immediately set about to turning it into a boarding house. And we moved most of the family, most of the time, into one bedroom. I had two other sisters, myself and my mother. And the other two rooms were filled with GIs because we lived very close to the USO. So, we’d have the soldiers, sailors and airmen throughout World War II living in our house.

And these were the inspiration.

I started building models, models of anything I could see and do. I could turn poker chips into wheels for a tank. And a lot of the Navy people that would stay at the house would send me boxes of balsa wood. And balsa wood was a strategic material. So, all of a sudden I had not only the materials and skill, but it was to the point where I could build things that would really fly.

VL: You were flight director for Apollo 11, the first space flight to put men on the moon, 45 years ago. Can you describe a little bit that experience?

GK: There are some events in your life that you’ll never forget. I had a team of young men — they were all men at that time — whose average age was 26. We had trained very well. I had full confidence in this team. We had some difficulties in our training process of working out the landing decision process, because there’s some point in the landing phase, where if you let the crew descend too fast, you fall into what’s called the Dead Man’s Box and you’ve lost a crew.

The real mission came along, and I have to make the 'Go/no-go' [decision]: Are we going to go down to the Moon this time or not? I have no reason to terminate the mission at this time, so basically I give the crew the 'go' for powered descent.

By this time we recognized, we’re going to be landing long. We’re not going to be landing in the place where we expected to land. We’re now starting to see, we’re moving down to what they call the toe of the footprint. And we know there are boulders down there, there’s craters down there and the crew’s going to have to take over manual attitude control and find a proper landing site.

But in the process of doing this, I’m watching the clock. And the clock indicates that very shortly we should have what we call a low-level alarm.

Now, I don’t know if you’ve ever driven in your car with the gas tank being empty, but that’s exactly the position we’re in right now because we’ve come to a point in our ability to measure the fuel in the tank where basically, we can’t measure it anymore. But we know by experience we have two minutes of fuel remaining at a 30 percent throttle setting.

Totally silent in Mission Control right now with the exception of one voice, and that’s my propulsion guy telling me the seconds of fuel remaining. And you go through '90 seconds.' And then there’s a pause and we’re listening to the crew. They’re giving me altitude, descent rate. Then it’s '60 seconds.' And then it’s '45 seconds.' '30 seconds.' And then about the time it’s 'fif-' ― all of a sudden we recognize, we’ve landed on the surface and the crew is going through shutdown.

And then it sunk in, when the people were cheering and applauding and everything else. And the crew had roughly about 10 seconds to celebrate, and then back to work.

VL: You said earlier you were a pilot, a military pilot. Did you ever want to be an astronaut yourself?

GK: I did in the very early days. In fact, it was probably in the first six to nine months. Because I really admired these guys.

But I really realized that I’m going to 'fly' more missions in my lifetime than any of these crews will ever fly. And I basically got the best job in the entire space program.

VL: Because you basically got to participate in it from the very beginning right through.

GK: Yeah, I flew over 33 missions as flight director. And in my career I was responsible for over about 120.

VL: In December 1972, NASA launched Apollo 17, the sixth and last mission to send astronauts to the Moon. How did you feel when that phase of the space program ended?

GK: I saw that phase coming. The teams in Mission Control saw that phase coming. And I was the flight director that launched Gene Cernan and his crew from Earth, and I also launched them off the surface of the Moon. So basically I saw the launch phase from both ends of it.

One of the responsibilities of the flight director, as you leave the surface of the Moon, the White House always has a message ready to relay to the crew once they’re safely in orbit. President Nixon’s words really drove this thing home, because he said this may be the last time in the century. And it just ― this is a hell of a way. And it really got us.

But that’s the job. We got the crew up in orbit and checked the spacecraft out, and had them on their way back home.

VL: Americans today seem to have more or less lost interest in the space program. There are probably people who don’t know that the Space Shuttle flights have ended or that we still have a space program. Why should we care? Why should Americans care about a space program?

GK: I believe there are many reasons.

I think the first reason is our nation is an exceptional nation. I believe that it's important for us to maintain this belief because we are representative of the best characteristics of a democracy. Basically the people of the world look to us, recognizing that we are powerful. Not because of our economic might, but because of our beliefs.

I think it’s important that as a nation, we carry that forward. And to do this, we have to demonstrate we are capable of doing very difficult and challenging things. Space is difficult and challenging. I think it can and did unite the nation at that period of time. It united the world.

Space then creates the technology ― a very difficult technology ― that we need to keep the economic engine of our country going. We need to get that engine started so we can actually provide for the people of our nation. We need to get a healthy set of industries that basically are made in America right now, where we build and create these things that cannot be replicated in any other part of the world.

We need to challenge the colleges and universities for the curriculum they need to continue to expand human knowledge. And we need some direction for our young people to look forward to, so they will be motivated to do the hard things.

GK: There are a lot of perspectives on space. [The NASA one] is currently to go rendezvous with an asteroid, etc.

I believe that’s too limited a mission. I think you need a broader mission. I think we need to really look at establishing human presence in space beyond the near-Earth environment like we have in the International Space Station. I think going back to the moon and [establishing] a long-term base in the moon would make a heck of a lot of sense.

Recently, I saw one of the former NASA administrators talk about a Mars fly-by in 2021, which is only seven years from now. Well, we have the knowledge. The books have been written. We have all of these things. All we got to do is the will to get it. And we have a spacecraft called the Orion that basically is capable of transporting people there.

So, I think Griffin’s proposal to do the Mars fly-by in seven years is absolutely within our ballpark. All we need to do is to have the dream and the will to do it.