‘Go Back Where You Came From’: The Long Rhetorical Roots Of Trump’s Racist Tweets

At a ceremony Monday at the White House, President Trump defended his racist tweets against Democratic lawmakers. The language used in that tweet has a long history connected with nativist political movements in the U.S. Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

When President Trump tweeted his racist remarks Sunday, asking why certain Democratic congresswomen don't just "go back and help fix the totally broken and crime infested places from which they came," he did not just take aim at the four young women of color — three of whom were actually born in the U.S.

He did so using a taunt that has long, deeply entrenched roots in American history: Why don't you just go back where you came from?

The question doesn't always appear in those precise words, nor does it always surface in the same situations. And it doesn't always get directed at the same groups of people — far from it, in fact. But more often than not, it conveys the same sentiment: You — and others like you — are not welcome here.

"There have been different phrases that have been used," says Michael Cornfield, a scholar of rhetoric at George Washington University, "but the idea that we don't have any more room for people, or those people don't look like us, this is a long, ugly strain in American history."

Jennifer Wingard, a University of Houston professor who has looked at rhetoric and immigrant communities, traces this sentiment at least to 1798, when the U.S. passed a series of laws — together known as the the Alien and Sedition Acts — that were aimed at making citizenship more difficult for immigrants and deportation easier for U.S. authorities to carry out.

"The legislation is actually constructed for the ability to remove immigrants who are saying things against the U.S. government," she says, explaining that these laws were passed in a tumultuous political climate.

"We were starting to see different political parties and different politicians arguing for different ways that the government should be run. And it just happened that politically, they could try to maintain and try to withhold the status quo by putting it on the backs of immigrants."

Those laws established a pattern, she says, which would resurface with new waves of immigration and new perceived threats — from the Great Famine in Ireland and the Spanish-American War, to the Great Depression and the attacks on Sept. 11.

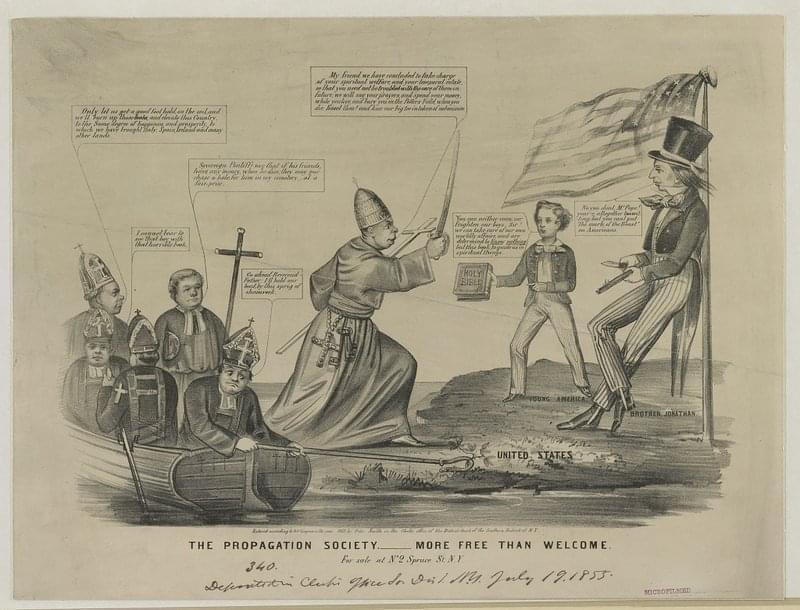

This cartoon, published around 1855, reflects the pervasive anti-Catholic sentiment of the era — perhaps best epitomized by the rise of the Know-Nothings, a nativist political party. Here, Catholics, led by the pope, are depicted as an invading force of foreigners, rebuffed by an Uncle Sam who likens them to the anti-Christ.

"Every wave of immigration that gets in sees the next wave as the threat. That is the wave that is now going to take the jobs, that is now going to take things away," Wingard says. "The latest flow in is always the one that seems the most threatening."

Alan Kraut, a scholar at American University who is writing a history of anti-immigrant feeling in the U.S., says he saw this kind of thing play out firsthand when he was a child growing up in the Bronx.

"When kids had a fight in the street and the kids were from different ethnic groups, one kid would often say to the other: 'You and your parents go back where you came from,' " Kraut recalls.

"You know, it could mean Brooklyn. But it could also mean go back where you came from — you know, Russian Jews who came to the United States, southern Italians who came to the United States, Puerto Ricans newly arrived," he continues. "So when this came out of the mouth of this president who's from Queens, it sounded almost like a child saying that in my memory on the streets of New York."

The process renews often, Wingard says, and she says the sentiment remains steady even if the names of the targeted groups change.

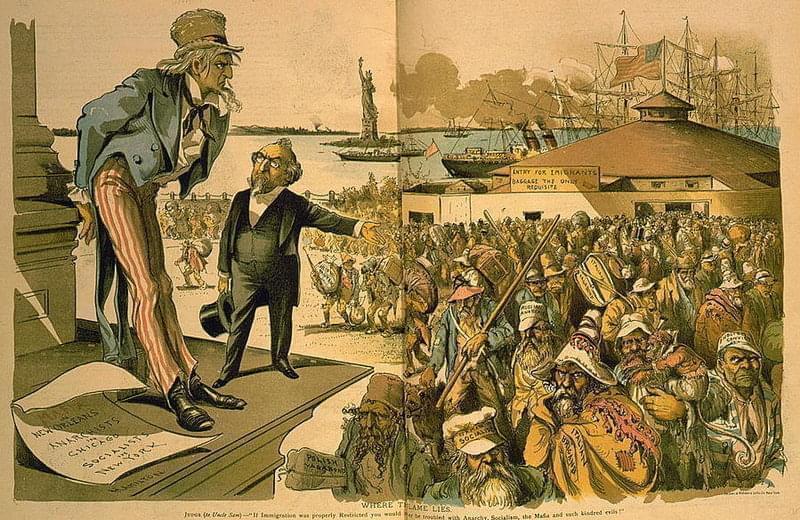

A cartoon, published in 1891, titled "Where the Blame Lies." In it, a man gestures toward a crowd of immigrants — including the "German socialist," "Italian brigand," "English convict," etc. The gesturing man tells a sagging Uncle Sam: "If Immigration was properly Restricted you would no longer be troubled with Anarchy, Socialism, the Mafia and such kindred evils!"

"There's a fancy theoretical term — it's called a palimpsest," says Jennifer Wingard, a rhetoric scholar at the University of Houston. A palimpsest, she explains, is a text that has been erased and overwritten — but that nevertheless continues to bear many of the markings and meanings largely concealed beneath the new writing.

"They carry these sentiments that we have seen over centuries, but then they get repurposed for the current moment — and a phrase like that [racist taunt] becomes almost like a shorthand for anti-immigrant sentiment," Wingard says. "You know, 'go back where you came from' is the same as 'go back to your own country' is the same as 'you are not allowed here' is the same as 'no immigrants allowed.' Yet it carries all of this historical shorthand with it."

Cornfield says it's partly the statement's variability that makes it so powerful.

"It plays to the fear that somehow America is getting too full or that the mixing of ethnicities and races would somehow aggravate issues," he says. "It's a potent phrase and part of its potency is its ambiguity."

Its simplicity, too.

"When you use a phrase like this, you're just asking people to forget about context and forget about policy choices," he adds, "and just get angry at people who don't look or sound like you do."