Illinois Issues: In The Red

The problem with the budget approved by Democratic lawmakers in May is simple: It did not include funding to cover its spending. Even though the proposal included cuts, it was somewhere between $3 billion and $4 billion short of revenue to cover costs. Wikimedia Commons

Illinois' leaders have yet to present a plan for a balanced budget. The longer they wait, the harder the task will be.

House Speaker Michael Madigan calls it the top issue facing the state. “Legislators did not agree with the governor's unbalanced approach, so we passed a plan that included hundreds of millions of dollars in spending reductions while protecting middle-class families and others who struggle by increasing funding for schools and preventing damaging cuts to public safety and services for the elderly, children and the developmentally disabled,” he wrote in an opinion piece published in The State Journal-Register earlier this month. What he failed to mention is that the plan Democrats sent to the governor may have made cuts, but like the proposal Rauner made back in February, it was billions of dollars out of whack.

That’s right. It’s August and not only is there no budget, neither the governor nor the legislature has presented anything close to a legitimate plan.

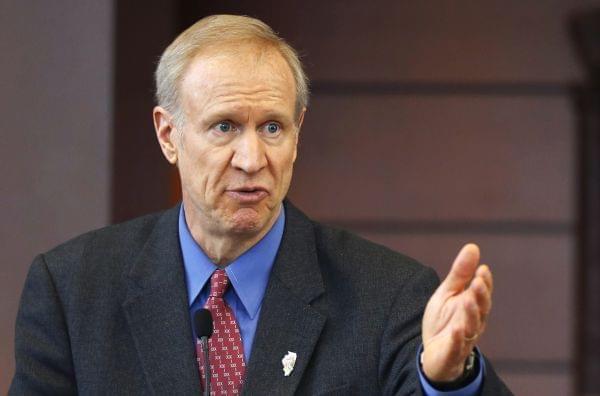

The governor laid out his vision for the budget first, so let’s start with the problems in that proposal. Rauner’s plan adds up on paper, but it relies on savings from policy changes. Some of these concepts would be difficult to realize in the current fiscal year and at least one would be impossible. The governor’s plan counted on $2.2 billion in savings that would be achieved by reducing public employee retirement benefits. It appears that the Illinois Supreme Court’s recent invalidation of a law that would have cut pension benefits precludes the governor’s plan. He maintains that his concept is constitutional. But in the context of the Fiscal Year 2016 budget, the outcome of that debate won’t matter. It is typically unwise to make predictions about Illinois politics, but it seems a safe bet to say that such a proposal will not be approved by the legislature and clear the inevitable court challenges in time to realize savings in the current fiscal year.Jamey Dunn reports on the problems with the current budget proposals and how delaying the pain of passing a spending plan is making the situation worse.

Rauner’s plan also counts on $655 million in savings from employee health care. This goal would have to be achieved through collective bargaining. So far, those negotiations do not appear to be going smoothly. Rauner has vowed not to lock out state workers, but a recent statement from the American Federation of State County and Municipal Employees Council 31 accused him of trying to force a strike.

In an analysis of Rauner’s proposal, the Civic Federation, a Chicago-based nonpartisan policy research organization, said: “It relies heavily on projected savings that do not appear to be achievable or prudent in light of the State of Illinois’ obligations and long-term policy objectives.”

The problem with the budget approved by Democratic lawmakers in May is simple: It did not include funding to cover its spending. Even though the proposal included cuts, it was somewhere between $3 billion and $4 billion short of revenue to cover costs. Democratic leaders say that Rauner had the option of using his veto pen to make line-item cuts. He opted not to do that and instead vetoed all of the budget except spending on K-12 education.

Bringing the state’s spending and revenue in line will be no easy endeavor. The January rollback of the income tax rate under the temporary tax increase means that this is the first fiscal year to fall entirely under the lower rate since the plan was enacted in 2011. Illinois will lose an estimated $4.6 billion in annual revenue in FY 16. To make matters worse, lawmakers did not address the shortfall in last fiscal year’s budget. Instead, Democrats approved a plan that underfunded many services. State agencies, however, did not reduce their spending accordingly.

The difficulty of the task for FY 16 is surely part of the reason that neither the governor nor the legislature has put forth a balanced budget.

Even without a full budget, court orders and legal agreements are keeping much of state government going. Employees are being paid. Medicaid money is going out. Pension payments have been made, and tax dollars that go to local governments are automatically distributed. More than two thirds of state funding continues to flow.

The more money that is being spent as the clock ticks on the stalemate, the fewer options Rauner and lawmakers will have to make a budget work. You can’t cut what you’ve already spent. For example, Rauner’s plan calls for a drastic reduction to the tax money the state distributes to local governments. This concept is not popular among lawmakers and previous proposals to reduce revenue sharing have been quickly stifled by vocal lobbying from mayors. But whether or not it is a good or a popular idea, it can’t be on the table once that money has gone out.

Senate President John Cullerton suggested that lawmakers and the governor hit the "reset button" on the budgeting process.

Left out of Illinois’ budget-free spending bonanza is the state’s social safety net. Illinois does not provide these services — such as addiction treatment, support for families with autistic children, daycare for low-income families and in-home care for the seniors. Instead, it contracts with providers, typically nonprofit organizations, to do the work. Several of these groups came to the Capitol last week to warn that if the lack of funding continues, they would have to cut workers and reduce their capacity to serve some of the state’s most vulnerable citizens. “What you’re going to see is this trickle become a stream, become a flood as program after program is closed or suspended or access restricted and more and more of our employees laid off or terminated,” said Jim Runyon, executive vice president of Easter Seals Central Illinois. Runyon warned that if organizations like his have to lay off employees or stop operations, those workers might move on. He says it would take at least six months to train new staff. “We can’t stop and start on a dime. This is much more like a freight train, and we all see where this freight train is headed.”

The other large area of spending that is not being funded is higher education. Students may be starting the school year without financial assistance from the Monetary Award Program, otherwise known as MAP grants. Rauner has called for cutting state funding for higher education by more than 30 percent. Again, cuts that deep are unlikely to be popular in the General Assembly, especially among lawmakers — from both parties — who have colleges and universities in their districts. But as money continues to go out the door, there will be fewer options to soften the potential hit to higher education.

Meanwhile, Democratic leaders and the governor are locked in a battle that is not directly about either of the proposed spending plans. The governor sees the crisis as an opportunity to make changes he says are key to the state’s recovery. He calls his raft of business-friendly ideas the Turnaround Agenda. “We are constantly kicking the can, not reforming, not passing true balanced budgets. We’ve just got to change and now is the time,” Rauner said during a news conference last week. He has said that Madigan and Democrats should either get on board with some of his proposals or pass a tax increase to fund their spending plan.

But many of Rauner’s ideas are viewed as existential threats to labor unions that would never make it through the Democratically controlled legislature. In addition to his economic policy proposals, Rauner backs term limits on elected officials and changes to the way the state draws its legislative districts. The governor did say last week that he is willing to back off on some of his wish list. But he would not get specific about what he would give up.

As for the lack of a budget, Rauner places the blame on Madigan and “politicians he controls,” while the House speaker accuses the governor of acting “in the extreme.”

“I expected that there would be a long protracted discussion among the governor and everybody in the legislature. I’m not surprised,” Madigan said during one of the weekly press conferences he has held as the House has been in session this summer. He may not be surprised, but he is also not publicly offering any workable path to reconciliation. When asked what his strategy is to reach an agreement and eventually produce a budget, he said: “The strategy is for everybody to be reasonable and to function in moderation and not in the extreme.”

Conflict between Gov. Bruce Rauner and House Speaker Michael Madigan has, at times, overshadowed the budget.

According to the state’s Constitution, both the governor and lawmakers have a role in getting the budget completed. First the governor must present a plan that “shall not exceed funds estimated to be available for the fiscal year as shown in the budget.” After that happens, the legislature “by law shall make appropriations for all expenditures of public funds by the State.” These expenditures are not to exceed the amount of revenue estimated to come in.

Senate President John Cullerton suggested in July that lawmakers and the governor restart the budget-making process.

“His plan is dead. Our plan is dead,” Cullerton said at a news conference. “I’d like to suggest we hit the reset button and start over.” He called upon Rauner to submit another budget proposal. Before that press conference had even ended, a spokesperson for the governor responded by bashing the Democrats’ budget and urging Cullerton to support Rauner’s agenda.

But Cullerton could be on to something with the reset concept. There seem to be few ways out of this deadlock without those involved taking a fresh perspective on the issues at play. In the past, the legislature has had some success hammering out compromises — both on policy and fiscal matters — in smaller working groups. That was already attempted during the spring session with nothing to show for it. But perhaps a do-over is in order.

As a journalist, I don’t love the idea of calling for closed-door meetings. But if some substantive conversation could take place without finger pointing or grandstanding for cameras, such groups could start fresh at the basics of negotiating: working with an attitude of mutual respect and building upon areas of common ground. Maybe some of the faces of those working in and with such groups would need to change if there are personality differences too strong to overcome. At this point, when the state is a month and a half into the fiscal year with no budget and no resolution in sight, going back-to-basics seems like a good place to begin.

Links

- Gov. Edgar to Gov. Rauner: Back Down And Compromise

- Rauner, Madigan ‘Circling Like Dogs’

- Rauner Vetoes IL Budget, Cites $4 Billion Deficit

- Gov. Rauner Couldn’t Veto The Budget If He Tried

- Rauner Sticks To ‘Turnaround Agenda’ Despite Facing Government Shutdown

- Rauner Warns Cabinet Members To Prepare For Cash Crisis

- Rauner Prepares Closures, Spending Cuts If No Budget Agreement