Illinois Issues: No Place To Call Home - Pt. 2

Despite the bucolic appearance, rural areas are also settings for homelessness. David Wilson

The second installment of a three-part series on homelessness looks at how the problem plagues Illinoisans in the state’s rural reaches, too.

A quieter, harder-to-detect problem than its urban counterpart, rural homelessness nonetheless leaves its mark on people and communities.

“I think the perception for many people is homelessness is primarily an urban problem that they associate with folks you might see out on the street who have literally no place to go,” says Bob Palmer, policy director for Housing Action Illinois, a statewide advocacy organization. “But we really try to make the point that there’s homelessness in all parts of the state.”

Rural homelessness is more hidden than the urban kind for various reasons. People who otherwise wouldn’t have a place to stay might go on an extended visit to a friend’s or a relative’s home, or they might “couch-surf” among the homes of multiple friends and relatives.

There are other strategies, too.

“In the summer, if you can believe it, people who are homeless are actually camping,” says Christopher Merrett, director of the Western Illinois University-based Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs.

“You wouldn’t necessarily know, if you’re at a state campground, if that person in the next slot was actually homeless,” says Merrett. “You’d think, well, maybe they’re just out for the weekend like we are, to roast wieners and make s’mores. But they’re probably not making s’mores.”

How do people in rural communities wind up homeless? Circumstances vary, but often it comes down to the stock of affordable housing, especially for people earning low incomes, Palmer says.

A rent hike, for example, might simply be too much of a strain for a household already living paycheck to paycheck. Finding a new place to live can prove challenging because affordable housing options are limited.

Rural homelessness is interwoven with other types of socio-economic issues, too, such as mental health or substance abuse problems, inadequate public transportation, lack of education or training and scarce opportunities for finding long-term and decent-paying work.

Michael Carlson has lived at the Galesburg Rescue Mission and Women’s Shelter, a shelter for homeless people located in west central Illinois, on and off for about a year. Originally from nearby Knoxville, the 62-year-old has held jobs as a laborer, a factory worker and a truck driver.

For a time, he lived with and cared for his father, who eventually moved to a nursing home and died. He says he found himself homeless after losing a couple of jobs, so he turned to the Rescue Mission for food and shelter.

His most recent job, just a few months ago, was with a traveling petting zoo in Missouri. Carlson fed the animals, cleaned their pens and helped set up as the zoo moved from town to town. But once the warm-weather season was over in Missouri, the zoo headed to Texas. Unemployed again, Carlson returned to the Rescue Mission.

He plans to find another job soon, preferably close to home. “I was born and raised here. I kind of like it here,” he says. “There’s got to be something out there.”

The Galesburg Rescue Mission

Homelessness can happen to anyone, including doctors, attorneys and other people with professional occupations, says David Scholl, director of the Galesburg Rescue Mission. In his 27 years of working with the homeless, he has found the most frequent underlying cause of their situation is addiction — to alcohol and illegal drugs. The Rescue Mission aims to meet people’s physical needs for food and shelter, as well as their spiritual needs. “We believe only Christ can transform hearts and lives. It takes some time,” Scholl says.

At Good Samaritan House in Carbondale, where Mike Heath is executive director, a mix of federal funding, state dollars and donations pays for a range of services. Good Samaritan offers a 30-day emergency shelter, longer-term transitional housing that primarily serves veterans and people with substance-abuse problems and helps them find work, a food pantry, a soup kitchen that serves three meals a day and emergency financial assistance.

Heath says one of the most important services Good Samaritan House offers is giving people a phone number and an address to put on job applications and a place to receive calls. “You won’t get a job if you don’t have that.”

He has seen demand for services rise dramatically during the past year or so. For example, the soup kitchen served 33,900 meals last year — an increase of more than 25 percent when compared with the soup kitchen’s six-year average of 27,000 meals a year

“Basically, I would say it’s the economy doing it. We are in a poverty area in Illinois, probably the worst, southern Illinois,” Heath said. “There’s a lot of layoffs going, coal mines shutting down, a few manufacturing facilities shutting down, universities having problems because they aren’t getting their state monies.”

He says existing shelters and programs just can’t keep up. “We always struggle to meet the need.”

The public funding that goes toward reducing homelessness comes largely from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development through its Continuum of Care Program. Among the goals of the program, HUD says, is to promote community-wide commitment to the goal of ending homelessness and to provide funding for efforts by nonprofit providers, and state and local governments to quickly rehouse homeless individuals and families while minimizing their trauma and dislocation.

Illinois is divided into 21 continuums of care. Chicago has its own, as does Cook County. Several other Illinois continuums of care consist of single counties, including DuPage, DeKalb, McHenry, and Champaign. About a half-dozen continuums of care in the state consist of multiple counties.

HUD’s help is crucial to the continuums of care and their ability to assist people, says Lori Sutton, assistant director for financial and human resources at the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs. Sometimes, though, HUD’s priorities don’t match up well with the needs in a particular continuum of care, especially one located in a more rural area.

“In our particular continuum, we have a lot of problems with family homelessness,” she says, referring to the West Central Illinois Continuum of Care that consists of McDonough, Henderson, Warren, Hancock, Adams, Schuyler, Brown, Cass, Morgan, Scott and Pike counties. The federal government has placed an emphasis on eliminating veterans’ homelessness — something that hasn’t been much of an issue in the West Central Illinois Continuum. There were eight homeless veterans in the region in 2014 and just five in 2015, Sutton says.

Sutton says the federal government also has emphasized ending chronic homelessness — a reference to people who have been homeless for a year or more, or who have experienced at least four episodes of homelessness in three years. That sort of homelessness is hard to track in rural areas, she says.

“That’s more (of what) you find in the urban areas. It’s easier to document,” she says. “A lot of our people do the couch-surfing and stuff, and we kind of take care of each other, so it’s hard to get it documented that they are chronically homeless.”

The current scope of the problem of rural homelessness isn’t entirely clear, experts say.

On November 19, HUD released a report saying that national homelessness was continuing to decline, especially among veterans, families, and people who experience chronic homelessness. In making the announcement, HUD also acknowledged that some communities continue to face challenges brought on by tight budgets, inadequate affordable housing supplies or other problems.

According to the HUD report, Illinois saw an increase of 0.5 percent in total homelessness during the one-year span between 2014 and 2015. The report also shows that between 2007 and 2015, homelessness in Illinois decreased by nearly 15 percent. The results are based on what HUD calls “‘point-in-time” estimates that attempt to count the number of homeless people on a single night in January every year.

While the federal government provides the bulk of public funding for fighting homelessness, the current lack of an official state spending plan doesn’t make the fight any easier. Merrett, of the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs, points out that rural homelessness has existed for many years, but this year, “the state budget crisis is making an ongoing chronic situation even worse.”

In September, the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless, CSH, Housing Action Illinois, and Supportive Housing Providers Association jointly released a report titled “The State Budget Impasse Is Causing Homelessness in Illinois: A Responsible Budget with Adequate Revenue is Urgently Needed.”

The survey of homeless service providers found that 90 percent of them said they already had taken, or soon would be taking, at least one of the following actions that would result in less assistance for homeless people:

• Limiting intake of new clients

• Reducing or eliminating services for current clients

• Laying off staff or reducing their work hours

• Eliminating programs

• Closing sites

At the same time, the survey found, 59 percent of providers were experiencing an increased demand for services because other providers were curtailing services.

The report noted, for example, how the forced closure of Delta Center Inc., a mental health agency in Cairo, has led more people to seek those same services through Family Counseling Center in Vienna, about 40 miles away. At the same time, Family Counseling Center, which is also affected by the lack of a state budget, has cut employees’ hours and made layoffs. Some employees are continuing to work without receiving paychecks.

Despite financial constraints, advocates for homeless people are coming up with creative ways to tackle the problem.

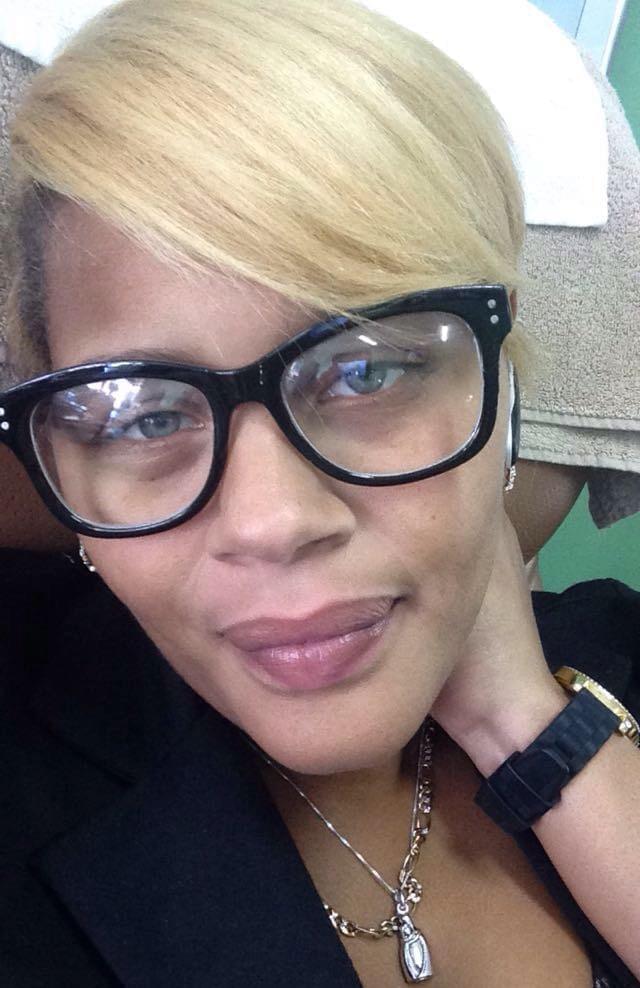

Now a community organizer and graduate student at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, Shannon Butler experienced homelessness as a child.

Shannon Butler, a community organizer in southern Illinois who has a bachelor’s degree in social work and is pursuing her master’s in social work at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, is completing an internship that puts her on the front lines of helping people who are homeless.

Based at the Carbondale Public Library, she works closely with the Sparrow Coalition, a community partnership addressing southern Illinois’ homelessness and poverty, and connects people to helpful resources, such as rental assistance, behavioral services, and job placement.

“That is my main target: people who don’t know that the resources are there, people that don’t have the tools to effectively look for these resources, people that don’t know how to communicate well in order to gain these resources,” Butler says.

The idea to create the internship developed after Butler conducted a research project on homelessness. Butler’s professor was taken aback by her findings and asked what could be done to help solve the problem.

Homelessness is an issue with which Butler has first-hand knowledge.

“As a child, I experienced chronic homelessness. We stayed in the women’s shelter when we got here, and we stayed in other missions before,” she says. “I felt like I had a home, and it was safe, and it was enjoyable. It was better than being on the street."

"But looking back, I would definitely say I felt like I was homeless, even though I had someplace to go. I didn’t have my own room, I didn’t have my own kitchen, I didn’t have my own bathroom, I didn’t have my own bed. Those are things that children long for.”

Adriana Colindres is a Galesburg-based freelance writer and is on staff at Knox College.

Illinois Issues is in-depth reporting and analysis that takes you beyond the headlines to provide a deeper understanding of our state. Illinois Issues is produced by NPR Illinois in Springfield.

This story is part of a series on homelessness. Click here to read the first installment, which focuses on homeless families and education.