Illinois Issues: Vicious Cycle Emerges With Opioid And Suicide Epidemics

VCU CNS/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

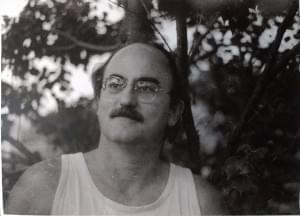

When Maria Luisa Tucker’s father died after swallowing a sizeable amount of a prescribed opioid, hydrocodone, she saw it as a personal tragedy. But recently, after investigating the opioid crisis and the connection to mental health issues, the journalist said she took a broader view of her dad’s 2006 suicide.

Last year, Tucker, a Brooklyn, New York woman, ran across an article in the New England Journal of Medicine titled “Suicide: A Silent Contributor to Opioid-Overdose Deaths.”

“And that's sort of when a light bulb went on for me. And I realized, like, Oh, well, you know, maybe the hydrocodone played a bigger part in my father's death. And I thought, and maybe this wasn't just a personal tragedy for me, maybe this was something that had been repeating itself.” (Maria Luisa Tucker’s article about her father’s opioid use and suicide for Tonic, a website and digital video channel can be found here.)

Tim Tucker Adams committed suicide in 2006 by deliberately overdosing on his prescription pain medication, hydrocodone.

Tucker’s not alone in thinking there could be a clearer link than what’s been widely reported in the medical community.

“I think we're all wondering about the connection between suicide deaths and opioid deaths. And it's likely that there are some connections for some of the deaths, and then for other deaths, not as much of a connection,” said Jill Harkavey-Friedman, vice president for research at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

“The issue is that many times people who are suicidal might be using substances like opioids or vice versa. There can be a lot of overlap, and it can be very hard to tell when somebody's died, was it an accident or did they purposely die by suicide,” she said.

The suicide prevention organization is funding a year-long online study beginning this month that that will look for connections.

The researchers will take information from about 100 relatives of those who have died by their own hand as well as people who have lost loved ones to opioid use and other drug-related causes. That will be compared against information gleaned from those who have experienced loss because of traumatic causes such as aggressive cancer or heart failure, wrote Jamison Bottomley in an e-mail. He’s a University of Memphis graduate student who is leading the study.

The importance of the research is to help survivors “as they struggle to make sense of a seemingly senseless death.” He wrote that as the suicide rates and opioid deaths climb, it's imperative that “we identify the most effective forms of support for these survivors.”

Volunteers participate in October in a Springfield Out of Darkness walk, which raised funds for suicide prevention.

At more than 1,470, suicides in Illinois are up 26 percent from 2010. Meanwhile, opioid deaths have skyrocketed to 2,202 – a number more than doubled from 2013. Nationally, opioid-related deaths are the highest they’ve ever been, and the number of suicides hasn’t been greater since the numbers were first collected 50 years ago. And the United States recorded a slight, two-year drop in the average life expectancy. “The combined number of deaths among Americans from suicide and unintentional overdose increased from 41,364 in 2000 to 110,749 in 2017 and has exceeded the number of deaths from diabetes since 2010,’’ wrote the authors of a January article in the New England Journal of Medicine, citing statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The combined suicide/opioid (along with a rise in self-inflicted gun) deaths is a perfect storm, says Joseph Troiani, a licensed clinical drug counselor and psychology professor at Adler University in Chicago.

“In addiction, you lose everything, you lose your family, you lose your dignity, you lose your job. One has to resort to things that they might never have dreamed of doing

as a result of their addiction. And as one addict said to me who survived a suicide — he said, ‘Doc, you get sick and tired of being sick and tired. And, you know, this looks like the best option out. You know, I've got to end it for myself. I've got to end it for everyone that I've hurt. I don't want to go on hurting people as result of my addiction.’”

Jeffrey Scherrer, research director at the department of Family and Community Medicine at St. Louis University, led a 2016 study to determine whether long-term chronic use of prescription opioids increased the risk of depression. Doctors, he said, had witnessed pain as a risk factor for depression.

The researchers wondered whether chronic, daily opioid use contributed to that.

“Most patients who use opioids for a short time, this is not going to be a problem for them.”

But for long-time daily opiate users, a cycle may be created in which they will more sensitive to pain, and need more medication to manage that increased pain sensitivity. That, he said, “further worsened their mood and emotional regulation. So we have a vicious cycle that is partially contributing to the persistence of chronic opioid use.’’

Tucker says of her father, who was medicated for after back surgery: “The hydrocodone might have played with his depression. I mean, I think, you know, it was a mix of things. But the hydrocodone I now realize, probably just made whatever mental health issues he had worse, and did not actually help the pain enough to make him functional on a daily level.’’

Scherrer said not all patients who die by suicide — or use opiates – have a mental illness. But for those who do, medication can mean the difference between life and death.

Liz Mitchell, a Rockdale woman who attempted suicide four years ago, said medication for depression has been key to her recovery.

Liz Mitchell is a teacher’s aide from Rockdale who attempted suicide four years ago. She had struggled with depression most of life, but it had gotten worse and she began to consider taking her own life.

“I was just having a really rough time of it. And I kept telling myself, if I could make it ’til Thursday, when my counselor appointment was, if I can make it ’til Thursday, I'll be okay. If I can make it to Thursday, I'll be okay. And then Thursday came around and my counselor had to cancel my appointment. I just couldn't handle it.”

After her attempt, a friend took her to the hospital where she was given anti-depressant medication. “Once I got on medication, it was a complete turnaround.”

Some may tell people with depression issues that they don’t need medication or counseling, she said. But that should be ignored. “I know it saved my life.”

In terms of excessive opiate users, doctors may at some point refuse to prescribe. And that can lead to unintended deadly consequences

“There’s some evidence emerging that patients who are … told by the doctor that they're not going to receive opioids anymore, some patients who are not helped with dependence, may be turning to suicide,” Scherrer said. In some cases, a physician may say: ‘Sorry, you don't have to go find somebody else to prescribe this medication,’ and that can lead to people taking their lives.’”

Troiani, the licensed clinical drug counselor and psychology professor at Adler, agrees. “Being in a situation where you look at what options you have — maybe treatment’s not available, maybe treatment’s not accessible. and you finally (say) the only option I have is to kill myself to put a stop to this misery. The other part of it is dealing with the pain. Addiction is psychologically and physically very painful.” Some individuals “might look at suicide as relief.”

Those suicides might be prevented if more opioid users were able to get professional help, he said.

Refusal to seek mental health treatment could play a role in the deaths of men like her father, Tucker said.

“I think — this is sort of my speculation — with men and men of a certain age, who are not willing or feel like therapy is helpful, and there's an additional component of feeling like, they just have to figure it out themselves. So the pills seem like the miracle answer, and I think they can be useful in some short-term capacity, but when they end up being relied on as the way to deal with not only physical pain, but some sort of mental anguish, and it

really can become a huge problem.

“I just think it's not a simple drug addiction problem. There's a lot more underneath it when you're talking about people with chronic pain, and people who have mental health struggles.”

Some of the keys to tackling the issue are education of the public and the medical community and a greater access to mental health services, Troiani says.

“Sometimes treatment capacity,” he says, is so low that “when somebody is ready for help or wanting help, desperation occurs when that help is not available. And if it's not available, the option of suicide becomes very real as a way out.”

The National Suicide Prevention Hotline number is 800-273-8255.

The Illinois Opiate Helpline is 833 234- 6343.

Illinois Issues is in-depth reporting and analysis that takes you beyond the headlines to provide a deeper understanding of our state. Illinois Issues is produced by NPR Illinois in Springfield.

Links

- Illinois Issues: The Pritzker Agenda

- Illinois Issues: New State Laws In 2019

- Illinois Issues: Piece Of The Pot - Money And Weed In Illinois

- Illinois Issues: When Walmart Leaves Town

- Illinois Issues: Ten Years Later, Has Illinois Learned The Right Lessons From Blagojevich?

- Illinois Issues: Illinois’ Birth - We Cooked The Books

- Illinois Issues: Gov. Rauner And The Folly Of Hubris

- Illinois Issues: Why Is Deerfield (Still) So White?

- Illinois Issues: Dear Governor-Elect Pritzker

- Illinois Issues: Third Parties - If Not Now, When?

- Illinois Issues: For Illinois Governors, Political Experience Optional

- Illinois Issues: The People Spoke—And We Listened