In Rare Debate Footage, Seeds Of Modern Politics

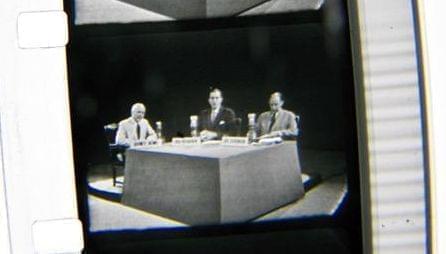

From left: ABC reporter Quincy Howe, Sen. Estes Kefauver and Gov. Adlai Stevenson in a still from the first TV debate between two presidential candidates. The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum has one of two known copies of the broadcast. Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

On Monday night, Americans sat down to watch one of the most anticipated presidential debates in the country's history. It happens to fall on the anniversary of the first and most famous presidential debate -- between Nixon and Kennedy in 1960. But that was not the first time two presidential candidates went before T-V cameras together.

That was four years earlier, when Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver and former Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson debated in the Democratic primary. Only two copies of that broadcast are known to exist. One is held by the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, which digitized and posted it online this year.

[MUSIC: "Heartbreak Hotel” by Elvis]

Beginning in the fall of 1955, Americans lived through a number of historic events.

That September, President Eisenhower had a heart attack. On December 1, Rosa Parks famously refused to take a seat at the back of a bus. And, on the morning of May 21st, the United States performed its first aereal test of a hydrogen bomb.

Democratic presidential contenders Stevenson and Kefauver met that night on ABC.

"My name is Quincy Howe. My job is to report and comment on the news for ABC radio and television," he said. "My assignment here in Miami is to discuss the campaign issues with Estes Kefauver and Adlai Stevenson, who are our chief performers this evening."

All three men were seated behind a table, with large microphones in front of them. The tone was serious and the men made points that seem substantive and deep by modern standards. Kefauver went first.

KEFAUVER: "A presidential campaign must not degenerate into a mere personal conflict, for candidates are only as important as the ideas they represent. I therefore welcome this opportunity for this discussion with Mr. Stevenson."

BOERGER: "it's well documented that the first time that two presidential candidates sat down in front of television cameras was this deabte."

This is Zak Boerger. He's responsible for the audio-visual collection at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. The film is in the collection related to Adlai Stevenson, who was governor of Illinois from 1949-53.

BOERGER: "You know when we had this film and we realized that we really needed to have it digitized and then made accessible to folks, the timing was pretty good. Because obviously this presidential cycle is anything but two polite, erudite, urbane men sitting around largely agreeing with each other but with minor differences. And of course they ended up as running mates that year anyway."

MACKEY: “And having long — "

BOERGER: “Right. Right."

MACKEY: “— minute after minute of substantive policy discussions."

BOERGER: “Right. Exactly. Policy discussions at 9 o’clock at night."

MACKEY: “I was waiting for Kefauver to say ‘Lyin’ — Lyin’ Adlai.’"

BOERGER: “‘Lyin’ Adlai.’ There’s only the one point where he calls Adlai on a speech that he gave where he pointed out that Kefauver had been missing a lot of his time in Washington. And of course Kefauver rightly pointed out that that’s because he had been traveling around doing the famous Kefauver Investigation into organized crime and so forth. So that wasn’t really a winning argument."

KEFAUVER: “I Was a little bit shocked, I must say, to find out that right afterwards (after the Minnesota primary), that you started having a whole lot to say about the fact that I’d been absent on some votes in the United States Senate."

This was a rare point of disagreement between Stevenson and Kefauver. It was also one of the few times in the debate when the candidates spoke to each other, instead of responding to questions by the moderator.

That was a point of contention among people at the time. A New York Times write-up referred to the broadcast as a “debate,” putting the word in quotation marks. And historian Jill Lepore says the same kind of thing happened four years later.

LEPORE: "When Kennedy debated Nixon in 1960, ABC News refused to call it a debate. Because they just felt like that was kind of a cheap trick on the part of the campaigns, that they were getting credit for debating when they were really not willing to debate one another. I think that’s some of a squirreliness around some of the Kefauver-Stevenson ’56 debate as well."

Lepore is a professor at Harvard. She's also a staff writer at The New Yorker, and this month wrote an essay on the history of American presidential debates.

She says back in the 1950s, formal debating was a familiar part of American life. She says it was a spectator sport; people actually would go watch local high school and college debate teams.

So they knew what a debate was — and what a debate wasn't.

And one thing a debate was, is people arguing points with each other, not just a moderator.

HOWE: “Well I’ve asked you gentlemen quite a number of questions. Aren’t there perhaps some questions you would like to ask each other, either on subjects that have come up this evening or comments you might care to make on statements that one or the other of you may have made earlier int he campaign. Would you like to ask Gov. Stevenson a question, Sen. Kefauver? And then (to Stevenson) return the compliment. I don’t want to do all the question-asking."

This has become a recurring pipe dream for debate organizers. Longtime Chicago Democrat Newton Minow has been involved in every televised presidential debate going back to 1960. Last week, after a speech at the City Club of Chicago, he was asked what he'd do to improve presidential debates.

MINOW: “If it were up to me … I would like to have them just talk with each other. That’s what I would prefer: how they differed with each other — without a moderator, without a questioner.

LEPORE: “The Commission on Presidential Debates and before them the League of Women Voters, who had sponsored the presidential general election debates, had really wanted the two candidates to pose questions to one another, to challenge one another, for the moderator to have less and less of a role."

Once again, Jill Lepore.

LEPORE: "But the campaigns prefer that the candidates speak only to the reporters who are serving either a panel of moderators or to a single moderator. And these people for a long time used to be both print reporters and television reporters. Now they’re only television celebrity anchors. And it was just easier, if you were a candidate, to imagine arguing strongly with a television personality than arguing with your political opponent."

It's well known that Stevenson was not a fan of television, particularly in the context of presidential politics.

But in the 1950s and beyond, television is where the people are. And Stevenson became a big proponent of televised presidential debates, for better and worse.

For her piece in The New Yorker, Lepore watched many of the past debates. I asked her whether they were useful for our democracy.

LEPORE: “Absolutely arguing about politics is essential for our democracy. I think the trick is doing it well is better than doing it badly, not only for the immediate outcome of the election, but for the general and broader political culture."

She says debtes are still assigned viewing in American schools, and this spring there was a lot of concern about what the raucus and at times vulgar Republican primary debates were teaching the next generation about how you make a case to an electorate.

LEPORE: “Abolsutely debates are crucial. The way they’re done isn’t great: the way they’re staged, what it means for the candidates to not actually be willing to talk to one another. But the much bigger question — which is the gridlock that we’re in as a polarized nation, where not only do we disagree with one another quite vehemently, we’re not even very good as listening to one another any longer."

[MUSIC: “Moonglow and Theme from Picnic” by Morris Stoloff]

After their relatively mild debate in May 1956, Stevenson won the Democratic nomination. And then he asked Kefauver to be his running mate.

In the general election the Eisenhower-Nixon ticket carried 41 states; Stevenson-Kefauver carried seven.