Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez Dies

Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, the populist leader of the oil-rich country, has died at age 58.

A fiery leftist, Hugo Chávez was a steadfast ally of dictators like Cuba's Fidel Castro while loudly opposing the United States. He claimed capitalism was destroying the world and tried to transform Venezuela into a socialist state. Millions of Venezuelans loved him because he showered the poor with social programs.

Yet Chávez, who ruled Venezuela from 1999 until his death Tuesday, was not able to turn the country's oil wealth into broad-based prosperity. At various times, the country experienced high inflation, food shortages and many other economic problems.

On the international stage, the countries that followed Venezuela's lead were some of Latin America's poorest and least influential. Chávez maintained fervent supporters throughout his rule. But in the end Venezuela was, in some ways, worse off than when Chávez began.

On the international stage, the countries that followed Venezuela's lead were some of Latin America's poorest and least influential. Chávez maintained fervent supporters throughout his rule. But in the end Venezuela was, in some ways, worse off than when Chávez began.

Chávez was omnipresent during his years in power. His face was plastered on billboards, his voice dominating the airwaves. His main vehicle was a Sunday TV show, Hello Mr. President, where he was both host and guest for hours at a stretch and ranted against American leaders.

Chávez had a gift for whipping the crowds into a frenzy, pledging that their country would be great. There was, of course, a more playful side that resonated with the masses, such as when he sang to his audience.

Support For The Marginalized

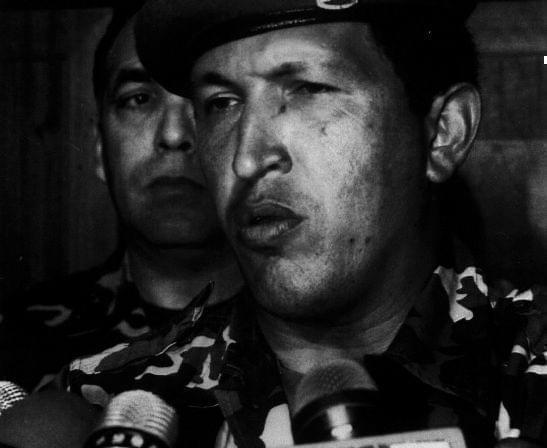

Chávez was born to a poor family in the Great Savannah in 1954. He joined the army as a youth and in 1992, he led a group of dissident officers who unsuccessfully tried to overthrow Venezuela's government.

Luis Miquilena, a prominent leader of the Venezuelan left who became Chávez's mentor, remembers convincing Chávez to give up plans for a violent overthrow after his release from jail.

Chávez began to see that he could rise to power democratically and then put his ideas into practice, Miquilena said.

Chávez won the presidency by a landslide in a 1998 election, tapping into the Venezuelan people's rising discontent with two corrupt traditional parties. He was inaugurated the following year.

Former Vice President Jose Vicente Rangel said Chávez's greatest success was making those who'd been marginalized feel that they were part of something bigger.

"Chávez took them out of the shadows," Rangel said. "That's his magic."

Opposition To The U.S.

Blessed with charisma, Chávez could be folksy and funny, and it helped him build an almost mystical connection with poor Venezuelans.

They, in turn, defended him — helping him win back power after he had been briefly overthrown in 2002.

Chávez used his political capital and a powerful base to launch what he called 21st Century Socialism — nationalizing companies, seizing farmland and forming alliances with like-minded leaders who opposed the United States.

In speech after speech, Chávez said that Latin America had liberated itself from what he called the American imperialist yoke.

Dreaming of uniting Latin America, the Venezuelan leader used his country's vast oil wealth to buy Argentine bonds and embarked on construction programs in Ecuador and Nicaragua.

He also helped poor Americans heat their homes, as touted in an ad for Citgo, the gasoline retailer owned by Venezuela. "I'm Joe Kennedy," the former Massachusetts Congressman says in the ad. "Help is on the way. Heating oil at 40 percent off from our friends at Venezuela at Citgo."

He also helped poor Americans heat their homes, as touted in an ad for Citgo, the gasoline retailer owned by Venezuela. "I'm Joe Kennedy," the former Massachusetts Congressman says in the ad. "Help is on the way. Heating oil at 40 percent off from our friends at Venezuela at Citgo."

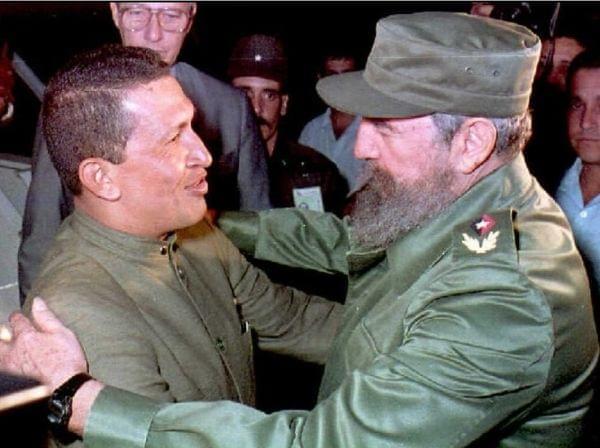

Chávez particularly irked Washington by providing 100,000 subsidized barrels of oil each day for Communist Cuba.

In exchange, Fidel Castro provided Venezuela with doctors and intelligence agents, while forming a close father-son type relationship with Chávez.

Friends And Enemies

An international left yearning for a magnetic leader was enthralled by Chávez.

Among those charmed was director Oliver Stone, who produced a glowing documentary in 2009 called South of the Border. In the film, the Venezuelan populist is thronged by adoring crowds and portrayed as an influential regional leader fighting American imperialism.

"He's a great example," Stone says. "If he succeeds it'll be the first time in Latin American history, except for Castro, where he's led the entire region away from United States' economic control."

The rosy gloss, though, often did not line up with reality.

Chávez supported a violent guerrilla movement in neighboring Colombia, according to internal Colombian government documents and interviews with former Colombian guerrillas.

Some of his closest allies included some of the world's most controversial leaders, including Iran's Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Syrian President Bashar Assad.

And at home, Chávez jailed some opponents and labeled his critics as degenerates and squealing pigs.

Michael Shifter, president of the Washington-based Inter-American Dialogue policy group, said that despite the elections Chávez won, his government was far from democratic.

"He, over time, concentrated power in his own hands. There were very few checks and constraints on his authority. He made all the decisions. No one else. Institutions like the judiciary were completely controlled by Chávez," Shifter said. "So in the end he really was an autocrat and despot."