Watch: Earth Gets Its First Look At A Black Hole, U Of I Researchers Contribute

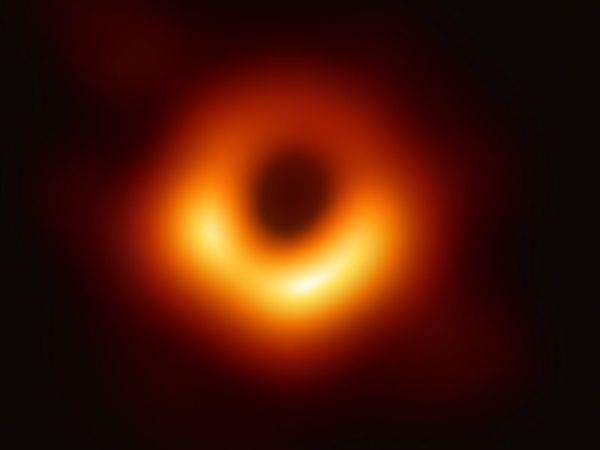

The first-ever image of a black hole was released Wednesday by a consortium of researchers, showing the "black hole at the center of galaxy M87, outlined by emission from hot gas swirling around it under the influence of strong gravity near its event horizon." Event Horizon Telescope collaboration et al

The world is seeing the first-ever image of a black hole Wednesday, as an international team of researchers from the Event Horizon Telescope project released their look at the massive black hole at the center of galaxy Messier 87 (M87). The image shows a dark disc "outlined by emission from hot gas swirling around it under the influence of strong gravity near its event horizon," the consortium said.

"As an astrophysicist, this is a thrilling day for me," said National Science Foundation Director France A. Córdova.

The enormous black hole is some 55 million light years from Earth, with a mass some 6.5 billion times that of our sun.

Córdova led a news conference in Washington, D.C., to discuss the team's finding — a process that took place simultaneously on four continents, as researchers held press conferences to share news of what they're calling "a groundbreaking result."

"You have probably seen many, many images of black holes before," said Heino Falcke, a principal investigator on BlackHoleCam. "But they were all simulations or animations. And this [image] is precious to all of us, because this one is finally real."

Pointing to the screen at the European Research Council's news conference in Brussels, Falcke said that the much-sought-after image "looks like a ring of fire. And it's actually created by the force of gravity, by the deformation of space-time, where light actually goes around the black hole, almost in a circle."

The black hole is some 100 billion kilometers across. But despite its massive size, anyone trying to find it in the night sky from the Earth's surface would face the same challenge if they stood in Brussels and wanted to see a mustard seed in Washington, Falcke said.

It's well known that a black hole's gravity is so overpowering that even light cannot escape its center. But black holes also dramatically affect their surrounding space, most obviously by creating an accretion disk — the swirl of gas and material that rapidly orbits their singularities.

"Black holes are the X-games of physics. They represent an unexplored extreme of space-time," as astrophysicist Adam Frank wrote for NPR in 2017. "While we now have good indirect evidence that they exist, getting a direct view of a black hole is the ultimate dream for a lot of physicists."

A breakthrough in black hole detection promises to answer a question that has dogged scientists since Albert Einstein proposed the existence of black holes in his general theory of relativity: how do you document the presence of something that's invisible?

Researchers at the Event Horizon Telescope project say they were able to create an image of a black hole by using a network of eight radio telescopes to create "a virtual telescope dish as large as the Earth itself," the National Science Foundation says.

University of Illinois Professor of Physics and Astronomy Charles Gammie co-led the theory working group of the EHT collaboration. He and his graduate students enabled the collaboration to determine the mass of M-87’s supermassive black hole, to constrain the black hole’s spin, and to shed new light on the physics of the black hole’s plasma jets.

A simulated illustration of a black hole shows the turbulent plasma in the extreme environment around a supermassive black hole. Researchers say they have created the first image of a black hole.

That array of telescopes is in places from Antarctica to Arizona. Before scientists can analyze data from the network, a painstaking process must take place. Each signal received by the telescopes must be synchronized wave by wave, using atomic clocks and a supercomputer to correlate and combine observations from around the world.

To find a black hole massive enough to potentially be visible from an Earth-sized telescope, the Event Horizon researchers focused on "supermassive" black holes that are found at the centers of galaxies.

The team focused on "the relatively small but 'nearby' supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy and the distant, but extremely massive, black hole at the center of the galaxy M87," Adam Frank wrote about the team's work in late 2017.