Illinois Fossil Hunt

I loved camping when I was a kid, and every year, we took a camping trip to Shades State Park in Indiana with our friends the Parkers. On these trips, Alan Parker (who played the role of a resurrected Charles Dickens in season one of “Prairie Fire”) would teach us how to hunt for fossils along the river. He taught us the basics of what to look for and how to hunt. And one year, I hit the jackpot. I found a perfectly preserved trilobite (an ancient sea creature) curled up onto itself sitting in the rocks next to the shore. I’ve treasured it ever since. But I haven’t had many opportunities since then to do much more fossil hunting. Life got in the way.

When I met geologists Joe Devera and Jeremy Breden, who are both geologists at the Illinois State Geological Survey, I jumped at the chance to go on a fossil hunt with professionals – and learn about the geology of Southern Illinois too. Fortunately, “Prairie Fire” producers Taylor Plantan and DJ Roach agreed.

If you don’t know much about the ancient geology of Illinois, there’s one major idea to keep in mind when you go fossil hunting: Illinois spent millions of years underwater. From about 500 million years ago to about 350 million years ago, the state was mostly a shallow tropical sea. During that time span, a lot of fossil-rich limestone and sandstone was deposited. So that means, nearly all the fossils you’ll find will be small ancient sea creatures and plants.

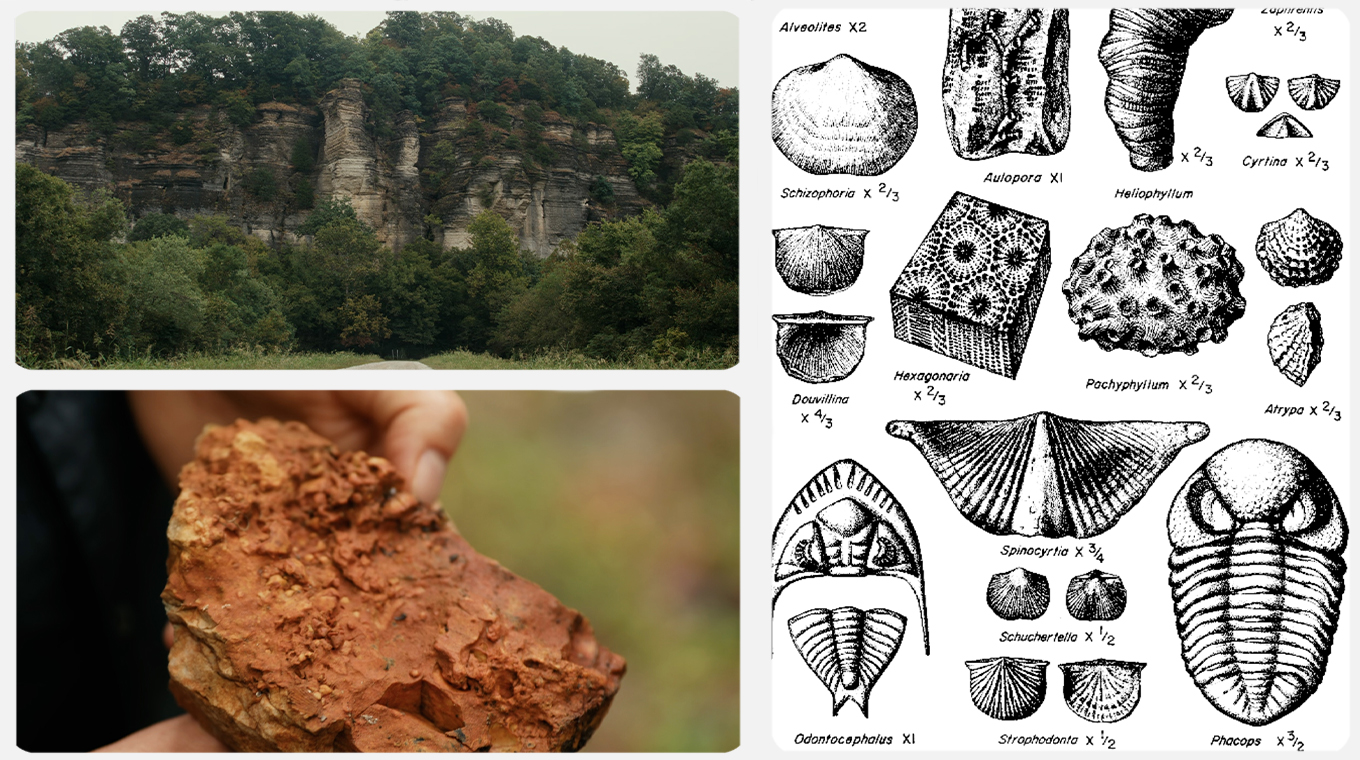

We started our hunt in the LaRue-Pine Hills cliffs area very close to the Illinois/Missouri border. These cliffs are made of Devonian Bailey limestone and Grassy Knob chert. Chert is made of silica (quartz). It’s hard, but it breaks easily. Joe and Jeremy pulled out a large stratigraphical map, which shows the age, type and layering of the kinds of rock in the area. Although the cliffs are spectacular to look at (and about 350 million years old!), they contain no fossils.

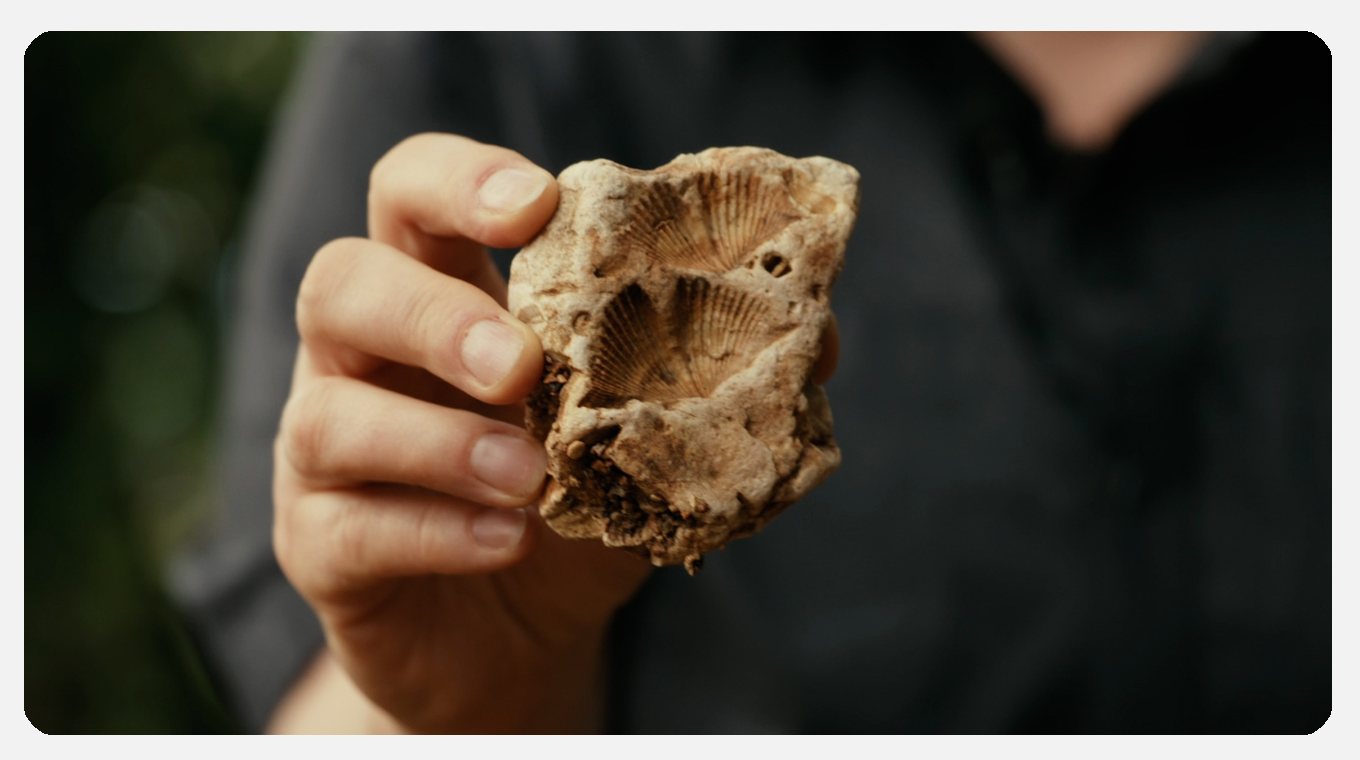

Next, we traveled to the Trail of Tears State Forest and hunted in a dry creek bed next to a hill. This proved more lucrative. The rock here – a lot of limestone and chert -- was younger, relatively speaking, and contained lots of fossils. I immediately found a large rock with a beautiful impression of brachiopods. Joe and Jeremy found fossils of small plants.

Our third stop was the noisiest. We drove to a roadcut along route 146, where Joe explained that ancient hot silica had created a divide in types of rock. Half the area was limestone, and the other half was chert. Here, we found small ancient plants called Archimedes, which look like spirals. Jeremy found ancient remnants of corals.

After lunch at Dairy Queen, we arrived at the last stop of the day at Milllstone Lake. We waited out a downpour, and then Jeremy and Joe showed us the dramatic “mass wasting” that happened near the lake when it overflowed (several different times) and washed over the land, revealing a huge rock formation made of chert. Near the chert cliff was an old cave system. And in abundance all around us were the most impressive (size-wise) fossil specimens of the day: large, long Archimedes plants. Some of these embedded plants were six inches long or more.

The day was a real education in how to fossil hunt properly. Joe and Jeremy emphasized that rocks are, in fact, ancient environments. Every rock tells a story, whether it contains fossils or not. Knowing where to go to find the right fossil-containing “strata” is a key to success. Patience and a good pair of boots help too.

Joe suggested we come back in the spring and hike deep into the woods to find some really spectacular fossils. Challenge accepted!

Online Fossil Hunting Resources:

Illinois State Geological Survey

Guide for Beginning Fossil Hunters