Musical beginnings

Music has always been an important fixture of WILL programing and mission, from the early days when WILL had its own in-house orchestra, to the 24-hour classical music service on WILL-FM and programs like Classical:BTS and Prairie Performances still providing a platform for local musicians today. Music served multiple functions during WILL’s first two decades on air. It was a way for the University to project a certain image of the institution—one that was cultured and high-minded—to those who tuned in across the country. It was also a way to draw listeners in so that they would be induced to listen to the educational content. Plus, music was simply a convenient method of filling airtime for the fledgling station.

Music and the development of radio

Inventor Lee de Forest conducts a radio broadcast with Mme. Mariette Mazarin of the Manhattan Opera Company on February 24, 1910. Public domain

Music was important in attracting the public to the technology of radio itself, even comprising what is considered the first public radio broadcast. On January 12–13, 1910, inventor Lee de Forest strung up microphones above the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City and set up a makeshift antenna on the roof to transmit Puccini’s Tosca, Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana, and Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci via telephone systems to listeners as far away as Newark, New Jersey. This was the first time any audience could hear a Met performance outside the opera house. Legendary tenor Enrico Caruso was among the voices carried over the airwaves.

In 1916, Frank Conrad, an early radio experimenter and the assistant chief engineer of the Westinghouse Electric Company, built his own radio transmitter and broadcast under the experimental license 8XF from his garage in Wilkinsburg, PA. During WWI, the government banned amateur radio broadcasting, but Conrad was relicensed with the same call letters after the war in May 1920. At the time, radio was mainly conceived as a two-way point-to-point medium; using one radio transmitter to reach a wide audience of “listeners” was a new concept. Conrad soon found his voice grew tired of making constant announcements of his call letters and location, so he began playing phonograph records on his Victrola over the air. His small audience of early radio enthusiasts began to grow, and listeners would even send in music requests, making Conrad “the first radio DJ.”

Harry Davis, Conrad’s boss at Westinghouse, saw an opportunity here. By starting its own commercial radio station, Westinghouse could capitalize on the radio craze and create a market for its new, ready-made radio sets that customers did not have to put together themselves. Westinghouse applied for a commercial radio license and replaced Conrad’s experimental station with the nation’s first commercial station, KDKA in Pittsburgh, which went on air for the first time on November 2, 1920, just in time to broadcast the results of the Harding–Cox presidential election.

Almost all of the early commercial radio stations initially relied on phonograph records as a primary source of programming. But Davis recognized that this was not going to be enough to build the industry and sustain listeners who could simply go out and buy the records themselves. Instead, Westinghouse became one of the forerunners in airing live music during the early 1920s. The company even had its own in-house band that would broadcast from a tent on KDKA’s roof, as auditorium’s acoustics were too live and created distortion. After the tent blew away during a particularly blustery rainstorm, the engineers decided to move the tent into the auditorium to dampen the resonance, creating the first workable indoor broadcasting studio.

Concerts in the lab

These live music broadcasts soon made their way to radio aficionados nationwide, including those at the University of Illinois. On November 1, 1921, The Daily Illini wrote, “Wireless concerts by famous musical artists will be held weekly in the radio laboratory of the Electrical Engineering laboratory…Using the regular University receiving equipment and the Magnavox amplifier to increase the volume of sound produced, the regular orchestra and vocal artists maintained by the Westinghouse Electric company at Pittsburg may be heard each evening and occasionally, famous musicians perform.”

By April 1922, the Electrical Engineering lab began playing these weekly concerts from KDKA and other stations to larger audiences in the Gym Annex via loud-speaking telephones. These musical broadcasts from external stations continued even after WILL—then known as WRM—came on air on April 6, 1922. Though WRM’s first half-hour show did not include music, the second broadcast on April 13 featured live singing with selections from the musical comedy Tea Time in Tibet by William Donahue. This was groundbreaking, as the Daily Illini wrote, “No other student musical production in America has been given by radio, according to L. G. Hunt, ’22, manager of the opera.”

Lanson Demming plays the E.M. Skinner organ in the Gregory Hall theatre in 1939.

Recitals by students and faculty from the School of Music were a fixture of early programming on WRM, made possible by the installation of underground cables connecting Smith Memorial Hall to the Electrical Engineering lab. The first recital broadcast from Smith Hall was given by violin professor Manoah Leide on December 7, 1922, featuring music by Swedish composer Valborg Aulin and Polish composer Henryk Wieniawski. The installation of underground cables to other campus buildings not only facilitated the broadcast of classroom lectures that were at the heart of WRM’s educational programming, but they also enabled the transmission of live concerts by university ensembles, such as the Men and Women’s Glee Clubs, the Choral Society, the Symphony Orchestra, and Illinois’ many bands.

Such musical programming proved popular to audiences far and wide. On November 21, 1923, the Daily Illini wrote that listeners from across the country had sent letters of appreciation to WRM for its broadcasting, particularly citing its coverage of Illini football games, lectures, and music recitals. The article concludes, “Some have said that the University’s music comes in stronger than that of many of the large commercial stations and that the selections played are liked by everyone.”

WILL’s main studio at Roger C. Sullivan Memorial Station.

At this point in the 1920s, WRM was only on the air for a short time each Tuesday and Thursday evening. But musical coverage continued as WRM expanded. In November 1928, when WRM changed its call letters to WILL and began broadcasting daily (5–6 pm and 7:30–8 pm), WILL’s first station director, Josef Wright, announced the daily schedule would include a series of 10-minute talks by various faculty members on a range of topics at 5:45 pm, preceded by musical programs by student and faculty musicians. The University Band would play Monday afternoons, and the Men’s Glee Club would sing Wednesdays. Other talent from the School of Music would be used to round out the programs.

And all that jazz

Not everyone was happy with WILL’s musical selections, however. Some locals complained WILL drowned out distant stations, which was irksome because WILL refused to play jazz or dance music. In the early 1920s, the commercial airwaves were dominated by jazz, blues, swing, ragtime, and dance band music. However, University of Illinois President David Kinley and other administrators felt that popular music “was not in keeping with the dignity of the institution.” After all, the University had conceived of the radio as a promotional tool for portraying the institution as a beacon of culture and higher learning.

This controversy surrounding jazz on the radio extended beyond WILL. On December 22, 1924, then-Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover commented, “The radio industry can’t live on an endless diet of jazz.” In addition to arguing for a tax on the sale of radio equipment to support radio stations without direct advertising, Hoover argued, “Right now I think the most important thing is improvement of what is put on the air.” The Chicago Tribune retaliated in an op-ed, writing, “We think that by including jazz and plenty of jazz a public service is performed. If we were out to reform the morals of our fellow countrymen by the radio, we should be more disposed to make the broadcasting of jazz compulsory than to prohibit it for the simple reason that it is the best friend of the informal dance at home.”

"What would the public think if we ‘blossomed’ out with jazz selections when we have a School of Music teaching the best there is in music?"

The Daily Illini, in keeping with the university’s notion of what an educational radio station should be, thought differently, arguing that commercials stations “care nothing about the advancement of art of music or of knowledge. They believe that the great mass of people would rather have the sort of rot they put out on the air. Doubtless, there are many, many people who demand it, but there are also many, many potential users of the radio who have never had a decent chance at anything else.”

The debate waged on while WRM/WILL continued to forgo popular fare. Throughout December 1927, the Daily Illini included letters to the editor on the subject. One student from the class of ’29 wrote, “We must realize that this is an institution of learning, and its voice is WRM. By the programs and music we are judged. What would the public think if we ‘blossomed’ out with jazz selections when we have a School of Music teaching the best there is in music? [...] No one cares enough about jazz music to send their children to school to learn it. Then why broadcast it?” Another student suggested that those who did not like WRM’s classical music offerings could buy a better radio set and tune into another station, concluding, “The station is yet in its infancy. Give it a chance, and perhaps your list for music will be satisfied.”

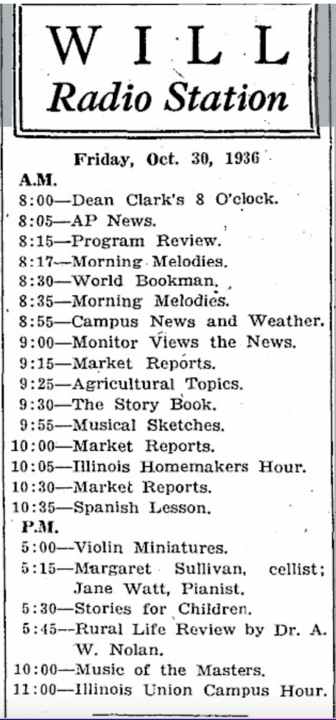

WILL’s daily scheduled printed in the Daily Illini, Oct 30, 1936.

However, another student insisted, “I wonder how many truly feel entertained when they tune in on the Glee club and organ recitals. I'm not saying there aren’t several (perhaps I'm not appreciative), but wouldn’t you bet a dime or so that the vast majority would look forward to programs by Bill Donahue, the Troubadours, and other good jazz orchestras of the campus … I say therefore what our WRM needs is not better talent but different talent.” In a rebuttal, Station Director Josef Wright wrote, “WRM cannot offer dance orchestra music, however good we may think it. That sort of thing can be had from hundreds of commercial stations, and there is certainly enough of it to fill the demands of the average fan.”

By offering something different to commercial stations, WILL managed to survive the massive hemorrhaging of educational stations squeezed out by the rise of commercial broadcasters during the ’20s and ’30s. WILL continued in its refusal to play jazz and other popular music until 1930, when Wright eventually convinced President Kinley the station should broadcast a wider variety of music while still remaining faithful to its educational mission. In a letter to Kinley dated March 6 of that year, Wright wrote, “While the purpose of Station WILL is not to entertain the public but rather to offer such educational matter as we have for the general benefit of our audiences, we have a very distinct duty, I think, in attempting to create a desire on the part of the radio fans to listen to all of our programs. And, having that desire, a listener will drink in the educational talks along with the entertaining features of the various programs.”

In response and to broaden the appeal of WILL, dance orchestras were integrated into the programming for lighter fare, along with fraternity and sorority singing groups’ renditions of popular songs. Classical music still comprised most musical selections, however, and in 1937, WILL bolstered its commitment to the genre by establishing its own chamber orchestra, the WILL Sinfonietta, which played live in the studio. As can be seen from WILL’s daily schedule for October 30, 1936, music now accounted for more than 20 percent of airtime. The prominence of music on WILL during its time as “The University of the Air” indicates those at the helm recognized music’s intrinsic value, not only as a means to bring in audiences, but also as a vital component of the station’s educational mission.