The Early Years

When WILL (then WRM) first came on the air in 1922, the American public, tired of the serious issues that consumed them during the war and bolstered by their newfound economic dominance, was restless and ready to be entertained.

The technology of radio was just beginning to enter people’s homes in the early 1920s. Developed gradually over the course of the late 1800s, radio had primarily been used to contact ships out at sea and was an invaluable military tool during World War I. In 1920 the Westinghouse Electric Company started the first commercial radio station, KDKA, in Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania, in an effort to build a market for their radio sets. By the spring of 1922, the radio craze had fully taken hold, with sales of radio sets, parts, and accessories totaling $60 million that year.

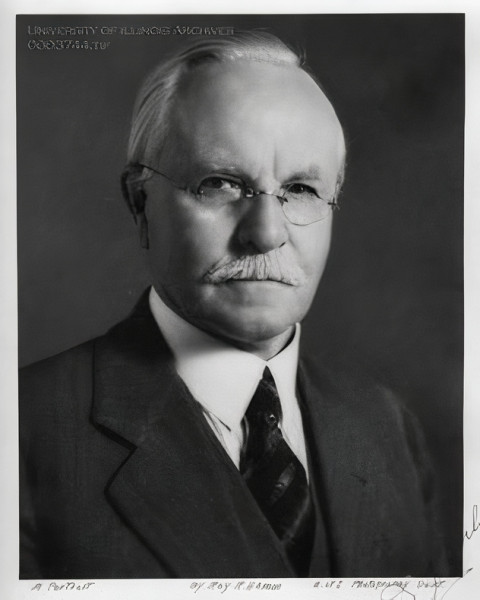

University of Illinois President David Kinley Photo Credit: Economics at Illinois

Universities were naturally at the forefront of early radio broadcasting as their physics and engineering departments experimented with transmitters and receivers. The Electrical Engineering Department at the University of Illinois was no different and had acquired an experimental radio license from the Federal Radio Commission in the summer of 1920, operating under the call signal 9XJ. Experimenting with crystal receivers and other radio apparatuses, the department began transmitting athletic scores to other radio amateurs and planned to add music. However, in December 1921 a government ruling mandated that stations making broadcasts for the general public acquire a Limited Commercial License.

Despite Kinley’s hesitancy, the University of Illinois applied for the license on March 3, 1922, which it received on March 28. On Thursday, April 6, WRM (or “We Reach Millions”) signed on the air for the first time. On that storied night, four men gathered around a 50-watt vacuum tube in the university’s electrical engineering laboratory and broadcast a thirty-minute program that covered Illini baseball and track, stories from the Daily Illini, and brief lectures on “Turning Cream into Gold” and “The Value of Parks for Towns of Illinois.” This inaugural broadcast could apparently be picked up within a 500-mile radius of the Urbana campus.Of course, this would require the approval of David Kinley, President of the University of Illinois from 1918 to 1930.

Kinley was philosophically conservative and regarded new technologies with suspicion. As a former economics professor, he understandably did not want to waste university funds on a gimmick. At this point, it was still unclear whether the novelty of the radio would wane like so many other fads of the time. However, Kinley realized radio could be a tool to publicize the university during a time in which various forms of media were vying for the public’s increasingly commodified attention.

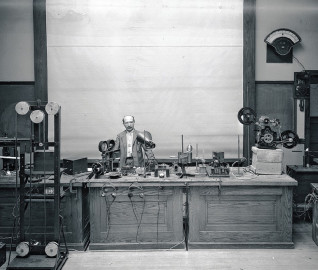

WRM studio in 1925. Photo credit: Illinois Alumni Magazine

WRM continued these weekly Thursday night bulletins while the station waited for supplementary equipment to be installed that would connect them to other campus buildings. Most of the early shows consisted of talks by prominent figures on campus and university news. With the supplemental equipment in place, they began broadcasting student plays, concerts, classroom lectures, and play-by-play reporting of football and basketball games. The Agricultural College also began using it for extension announcements.

Professor Joseph Tykociner Photo credit: University of Illinois Alumni Archives

Even as the station expanded its program offerings, it continued to serve as a working laboratory for faculty research and student instruction. Consistently on the forefront of new technology, the electrical engineering laboratory housed the only two vacuum tubes on campus, which were so fragile they had to be cooled with an electric fan and periodically shut off so they wouldn’t overheat. When the station was off the air, Professor Joseph Tykociner used them to make the world’s first talking picture. The department continued to try to improve the physical output of the station, and by the spring of 1923, WRM gained permission to broadcast with a 500-watt set, one of the largest in the country.

The radio station proved particularly useful in connecting far-flung alumni to the campus and breaking down barriers between town and gown. Especially instrumental in this effort was the broadcasting of Illini football games with superstar halfback Red Grange on the field. People who previously had no connection to the university soon became loyal followers of Illini sports and “synthetic alumni” via the radio, proving radio’s effectiveness as a PR tool as President Kinley had hoped. But when alumni suggested the university build a more powerful station outside of the laboratory, he balked at the cost.

Boetius H. Sullivan (second from right) in 1913. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Fortunately, in April 1925 a wealthy Chicago businessman named Boetius H. Sullivan promised the university a $100,000 endowment for the immediate construction, operation, and maintenance of a radio broadcasting station in memory of his late father, Roger C. Sullivan, a prominent figure in Chicago politics. Though neither he nor his father attended Illinois, the gesture was in recognition of the university’s work in making high-quality educational programming accessible to all. This was important to his father, who had to drop out of school at age 11 to support his family.

Though Sullivan ultimately reneged on his full offer one year later “owing to unforeseen circumstances,” construction still continued with the smaller sum he had already given. Completed in December 1926, the Roger C. Sullivan Memorial Station, from which WILL would operate for the next 16 years, was constructed on the south end of Illinois Field facing Wright Street. The station housed a 1000-watt Western Electric transmitter on the first floor and three studios on the second. Programs could also be broadcast from six remote studios in other campus buildings via underground telephone cables, and additional programs could be picked up from other buildings and rooms for a total of 27 remote control points.

Fight for the airwaves

WILL transmitter equipment from 1930

WRM had broadcast at 833 kilocycles until the spring of 1925, when it was moved to 1100 kilocycles. But as radio grew in popularity around the country, stations began to fight over the same frequencies, and WRM struggled to be heard. By 1928, when WRM changed its call letters to WILL, as many as 10 other stations were trying to broadcast on the same frequency. The Federal Radio Commission shifted WILL to 890 kilocycles and reduced its daytime and nighttime power to 500 and 250 watts, respectively. In addition, two powerful Chicago stations were only 20 kilocycles away and often drowned out WILL in much of the state.

WILL was not alone in this struggle to be heard. In the following years, the Federal Radio Commission’s bureaucratic licensing procedures drove many noncommercial stations off the air. By 1936, 164 of the more than 200 stations that had been established by educational institutions nationwide since 1921 were forced to shut down due to the bureaucratic red tape—a trend that was hastened by the Depression. These public stations’ spots were then sold off to commercial broadcasters.

Josef F. Wright, the university’s first Director of Broadcasting and eventually Director of WILL, continually lobbied the government to reserve radio frequencies for educational stations. WILL’s reach became so hampered that President Kinley questioned the future of the station. In the meantime, WILL broadcast during certain hours (5–6 pm and 7:30–8 pm each night) as part of a wavelength sharing agreement with stations KUSD of South Dakota and KFNF of Iowa. In 1933 the Federal Communications Commission (FCC)—formerly the Federal Radio Commission—restored WILL’s daytime power to 1,000 watts, and in 1935, due to Wright’s efforts, WILL finally received a suitable wavelength of 580 kilocycles—the same frequency WILL-AM uses today.

Kenneth Guge controlling the WILL radio studio in 1940

Despite these bureaucratic and technological setbacks, WILL stayed committed to its mission of providing high-quality educational programming and enriching cultural content to the public. As the “University of the Air,” classroom lectures were a staple of programming during the 1930s, constituting about a third of programming in 1933. Leading authorities in politics, finance, engineering, literature, social sciences, law, and agriculture lent their talents to WILL; no other station in the state had direct access to such a vast resource of knowledge.

Of course, Wright understood that WILL had to offer varied programming that would induce audiences to tune in, even though its primary focus was education, not entertainment. As such, in 1930 he convinced President Kinley to allow a broader variety of music to be played on air. Kinley had previously banned jazz and other popular music because he felt it was not in keeping with the dignified image he wished to portray of the university. Classical music had been a fixture of programming at this time, with student and faculty concerts from the School of Music broadcast live from Smith Memorial Hall, but now performances by dance orchestras were integrated for lighter fare.

Tune in next month for a deeper dive into the role music has played at WILL. Throughout this centenary year, we will be bringing you monthly articles that celebrate WILL’s 100 years of making waves for insight into its past, present, and future.