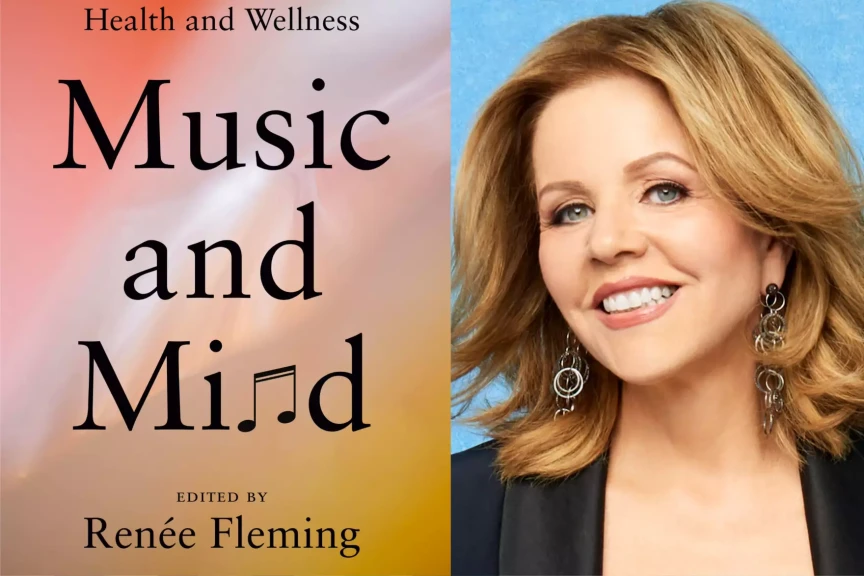

Book Review: “Music and Mind”

Soprano Renée Fleming may be best known as “The People’s Diva,” but in recent years, she has developed an interest in the connection between music and health. In her latest book, Music and Mind: Harnessing the Arts for Health and Wellness, Fleming has curated an anthology of essays from experts in the fields of science, medicine, and the performing arts. Each chapter offers unique insight into music’s power to heal, connect, and shape us and the new areas of research examining why this is.

The book opens with a foreword by Dr. Francis S. Collins, former director of the National Institutes of Health, who recounts the story of how he and Fleming first met. They were at a tony D.C. party attended by no fewer than three Supreme Court Justices shortly after Obergefell v. Hodges enshrined marriage equality into law in 2015. Tensions were high, particularly between justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia, friends and fellow opera lovers who disagreed bitterly on this issue (and much else). But when Fleming got up to sing a few American folk songs with the hired band and Collins on six-string guitar, the atmosphere in the room changed entirely. Soon, the partygoers joined in the singing, including the justices, demonstrating music’s power to heal and bridge divides.

This encounter spurred a partnership between Collins and Fleming, who had just accepted an invitation to serve as an advisor to the Kennedy Center, to advance the field of study surrounding music as a healing art. They began by assessing achievements in music therapy and neuroscientific research on music’s powerful effects on the brain, deciding now was the time to put more energy and resources into this burgeoning field. Their partnership resulted in the Sound Health Initiative, a cooperative between the Kennedy Center and the NIH, which has resulted in NIH research grants totalling $30 million as well as workshops, concerts, interdisciplinary projects, and finally, this book.

The 500-page anthology is composed of 41 chapters from 58 authors across the realms of science, literature, music, dance, visual arts, arts administration, education, and medicine. The ambitious collection casts a wide net to capture the endless ramifications of music in our lives. “With themes including the science of arts and health; creative arts therapies; artists, healing, and humanity; singing for health; and arts across the life span, Music and Mind has assembled the voices of leading figures in neuroscience and the musical and visual arts, providing an inspiring view of the emerging synthetic possibilities,” Collins writes.

In her introduction, Fleming outlines her own experiences of stage fright and performance anxiety and how turning to science helped her understand and overcome the physical manifestations that were threatening to derail her career. Her interest in the science behind music’s healing power intensified over the COVID-19 pandemic, which exacerbated existing upward trends of chronic pain, depression, anxiety, social isolation, and political division. She even offered herself up as a guinea pig to further this research, spending hours inside an MRI machine as scientists recorded her brain activity while singing, listening, and imagining singing. (Interestingly, her brain was most activated when thinking about singing.)

In addition to compiling and editing this book, Fleming has toured a series of Music and Mind presentations in collaboration with arts and community organizations, health care providers, and researchers to offer audiences the chance to learn about how the art forms they love can contribute to health care and scientific discovery. You can watch one such presentation with one of the contributors to this book, Pulitzer Prize-winning author (and Professor Emeritus at the University of Illinois) Richard Powers, televised by PBS affiliate KET.

In her introduction to Music and Mind, Fleming helpfully outlines the focus of each chapter and broader section, guiding the reader if they want to hop around to different chapters that interest them specifically. However, if you read the book from start to finish, the chapters are well-paced, alternating between scientific articles and artistic musings. The voices Fleming has assembled in this book are impressively diverse. Given the freedom to take the brief and run with it, each contributor brings their own deeply personal experiences of music and unique writing style to their chapters. These chapters run the gamut from rigorous scientific research to poetic love letters to music from writers such as Richard Powers and Ann Patchett.

If you wish to read about music’s role in the evolution of the human brain, Fleming points you to the essay by Dr. Aniruddh D. Patel, professor of psychology at Tufts University. If you are interested in the broad impacts of music education on child development, read Dr. Indre Viskontas’ chapter “Humans Are Musical Creatures: The Case for Music Education.” There are also numerous chapters about how music has helped the authors through various illnesses or how illnesses have affected the authors’ relationships with music, as in the essay by singer-songwriter Rosanne Cash, who underwent brain surgery for Chiari malformation in 2007.

Some of the authors use the opportunity to plug their own research or projects they are currently working on. For instance, cellist Yo-Yo Ma uses the prompt to contemplate larger existential questions about our connection with nature and how tapping into cultural traditions can restore healthy relationships with the world around us. Ma is currently working on a project titled Our Common Nature, where he visits sites that “epitomize nature’s potential to move the human soul, creating collaborative works of art and convening conversations that seek to strengthen our relationship to our planet and to one another.”

However much of the book you decide to read, be sure to start with the first chapter by Dr. Patel, “Musicality, Evolution, and Animal Responses to Music.” In this chapter, he poses a central question that will inform your reading of the rest of the book: “Is musical behavior, like spoken language, part of human nature? Or is music a purely cultural invention, a cherished tradition passed between generations but not engraved by evolution into our genes and minds?” In other words, is music borrowing evolved brain circuits used primarily in other functions, or did music have a hand in developing those circuits?

Patel argues that we are getting closer to being able to answer this age-old question with new tools and energy spent on the field of music neuroscience. He believes that our genes and culture evolved together (through “gene-culture coevolution”), yet strong evidence for this has been hard to pin down. “Musicality may be the first domain where this theory of mental evolution is convincingly demonstrated,” he says, supporting the broader implications and importance of studying music and the brain.

Overall, Music and Mind has something for everyone, with scientific information that is rigorous enough for those with a scientific background yet accessible enough for the layman to understand and appreciate. The book reads like a cocktail party of some of the smartest and most interesting people around whose conversations you can dip in and out of at leisure. The assemblage of all these prestigious contributors adds further proof to the book’s thesis that music has the power to connect people from all walks of life.