Edmond Dédé: An American in Paris

In honor of Independence Day, we’d like to introduce you to an American composer you probably haven’t heard of before. Edmond Dédé (1827–1901) was a violinist, composer, and conductor. Born in New Orleans, Dédé eventually saved enough money working in a cigar factory to book passage to France, where he studied with professors at the Paris Conservatoire. His first published piece, a song from 1852 called “Mon pauvre coeur” (“My poor heart”), is the oldest surviving piece of music by a Creole composer of color. For various reasons, Dédé’s biography has been clouded by misinformation and half-truths. Fortunately, historian Sally McKee cleared up some of the biographical inaccuracies in her 2017 book The Exile’s Song, giving us better insight into Dédé’s life and achievements. Read on to learn more about the fascinating story behind this little-known composer whose works are just now being rediscovered.

Previous scholars erroneously claimed that Dédé’s parents were refugees from the West Indies. But McKee recently discovered that Dédé’s great-grandparents had bought their freedom in 1785, and both of Dédé’s parents had grown up in the relatively large and prosperous community of free Creoles of color in New Orleans. Dédé’s father may have played clarinet in a militia band, spurring his son’s interest in music. After taking music lessons from both Black and white instructors, Edmond Dédé soon became a highly accomplished violinist.

New Orleans was an anomaly in the early 19th century in that the size and prosperity of the free community of color meant that segregation was largely impractical and difficult. Consequently, people of color were able to participate more fully in the musical life of New Orleans than in other US cities at the time. Even so, Black musicians still were disallowed from playing in the city’s major theaters and opera houses, which were the only full-time musical jobs available.

However, in the 1840s and 50s, more restrictions were being placed on the movements of free people of color, and they were pushed more into the margins of society. In search of more opportunities and fewer constraints, Dédé, along with hundreds of other free Louisianans, moved to Mexico after the end of the US–Mexican War in 1848. McKee explains, “a talented young musician like Dédé, trained by New Orleans’s finest teachers, was unlikely to have had difficulty finding employment in a war-ravaged Mexico City seeking to reignite its cultural life.”

Dédé returned to New Orleans in 1851. He worked in a cigar factory by day and played in music hall bands by night to save up enough money to travel to Europe. He eventually booked passage to France in 1856, entering on a falsified Mexican passport. Because Louisiana had barred free people of color from entering Louisiana if they had established domicile abroad, he had needed to obtain a falsified passport that stated he was born in Veracruz to return from Mexico. This workaround is just one example of how, as McKee explains, “The punitive legal restrictions placed on free people of color in the antebellum period compelled them to adopt evasive strategies.”

Once Dédé arrived in Paris after a brief detour in Antwerp and London, he sought out further musical training. Dédé had hoped to enroll at the famed Paris Conservatoire, but the conservatory only accepted students up to age 22, and Dédé was already 29 (though his Mexican passport listed his age as 24). The school allowed him to audit classes, and he took private lessons in composition, violin, and conducting with Fromental Halévy and Jean-Delphin Alard. He learned what he could as an auditor and through private lessons, likely supporting himself by playing in an orchestra at night.

Alcazar Theater, Bordeaux

Dédé eventually moved to Bordeaux in 1860 to work as a repetiteur for the ballet orchestra at the Grand Théâtre, the most prestigious theater in the city. In 1865, he was appointed music director of the Alcazar Theater, the first café-concert in Bordeaux. Cafés-concerts were music halls that presented popular music such as light songs, polkas, and waltzes. For over 30 years, Dédé catered to popular tastes at the various cafés-concerts he served, even though he aspired to be a composer of more serious “art” music, such as ballets, symphonies, and grand operas. Consequently, much of his music straddled the line between popular and art music. He produced 150 dances and 95 songs alongside six string quartets and several ballets, operettas, and overtures. However, he did not receive the same recognition for his art music as he did for his popular fare.

When popular tastes shifted in the 1880s from operetta to vaudeville, Dédé fell into obscurity, and his reputation suffered from his attempt to compose for both sides of the street. As McKee puts it, “On one side lay the elegant but highly competitive world of art music and on the other the brassy, lurid colors of the crowd. Dédé’s attempt to cross back and forth could not, in the long run, succeed, for reasons that had less to do with him and more to do with the changing market for popular music.” He moved to an even less wholesome venue, Les Folies-Bordelaises, around 1880. Though it was one of the hottest clubs in town, the omnipresence of policemen and raucous crowds clouded its reputation.

Even so, he continued composing the kinds of music he was passionate about. He wrote a grand opera in 1887 called Morgiane ou, Le Sultan d’Ispahan, considered the earliest complete opera score by an African American composer. He couldn’t find a theater to mount it in Bordeaux, so he and his wife moved in with their son, Eugène, who lived in Paris, around 1890. Still, he had no luck finding a theater in the City of Lights that would stage his opera.

Though Dédé never quite found the success he desired and faced racial prejudice in France, he still had many more opportunities and greater freedom of movement as a Black musician in France than he would have had in the United States. McKee explains, “With the exception of a few years in the 1870s, he had steady employment as an orchestra leader throughout the 1860s, late 1870s, and 1880s, perhaps not in the milieu he would have preferred, but he competed against French musicians for jobs and won them.”

After emigrating to France in his twenties, Dédé only returned to the United States once in 1893, where he was confronted with the grim realities of Jim Crow. Understandably, he stretched the truth about his achievements during his homecoming, wishing to present himself to his former community as the esteemed conductor, performer, and composer he longed to be recognized as in France—a success story of what a talented, hard-working person could achieve in a less racist society. Dédé even printed business cards that listed him as the chef d'orhdestre at the Grand Théâtre in Bordeaux, when he had only been a repetiteur.

Nevertheless, McKee writes, “He may not have prospered to the extent or in the way that he would have preferred to, but in the end the people who use him as an index of their hopes were right to do so.” Had Dédé never moved to France, he would have likely spent his life rolling cigars by day and pursuing his music by night, performing for mostly Black audiences.

Another layer of intrigue around this composer is that Dédé was involved in a shipwreck on his journey back to the States. He spoke to a reporter in Galveston, Texas, where he was recovering with family after the steamer he was on sank in the Gulf of Mexico. The reporter said that though Dédé, one of France’s “leading musicians,” had lost all his baggage and sheet music in the wreck, “Mons. Dede succeeded fortunately in saving his valuable violin, which is an Amati, purchased in France for 2000 francs.” However, when the news reached Dédé’s hometown of New Orleans, the story had morphed, with reports stating he had lost the 250-year-old violin to the watery depths.

Whether he even owned such a violin in the first place is unclear. It would have cost two to three times his annual salary at the peak of his career. But its existence helped to paint a happier picture for Dédé and was a symbol that marked him as a successful composer. McKee explains, “More than anything, there is a palpable wish in his self-presentations on this voyage to America to have a happy ending for himself. It was bad enough that he missed the chance of striding off a steamer to collect his trunks of clothing and sheet music and greet family and friends. The loss of everything, encapsulated by the violin, would have rendered the return of this native son a tragedy from which little dignity could have been salvaged.”

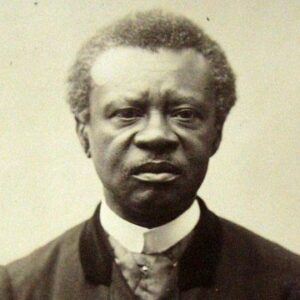

The composer later in life

The African American community in Galveston fêted their distinguished visitor from France and organized concerts in his honor. A month later, Dédé returned to his hometown. Unfortunately, not a lot had changed for the better in the 39 years since he last set foot in Louisiana. Newspapers in France could not have prepared him for the failures of Reconstruction he would have witnessed. “Dédé was returning to a city in the throes of an economic downturn and an upsurge in racist and anti-immigrant sentiment and violence,” McKee writes. “The African American community, now almost 27 percent of the population, was just beginning to feel the effects of new laws whose intent was to push them as far away from the white population as possible.”

In New Orleans, Dédé gave several concerts to great acclaim. One reviewer wrote, “Those who hold him to be merely a simple violinist are mistaken at least by half. He is at once a musician in the broadest sense of the term, a distinguished harmonist, an able composer; we have read of him that his compositions prove that he possesses a great feeling for melody.” Dédé is even reported to have played the guitar and banjo in his farewell concert, likely as a lighthearted encore since many concerts in New Orleans turned into balls with dancing at the end. He may have even toured to other cities in the United States, including Chicago, as later biographical accounts claim, though no documents substantiate this assertion. Regardless, realizing just how little improvement there had been in the circumstances of African Americans since the end of slavery, Dédé returned to France a disillusioned man. He moved back in with Eugène and his family in a small apartment in Paris. He died on January 5, 1901, at the age of 73.

Thanks to McKee’s scholarship, some of the misinformation surrounding Dédé’s life has been cleared up. What she has revealed is a more complex and interesting picture of the composer. The misinformation itself is largely a consequence of the racist world Dédé was operating in, as evidenced by the falsified documents he needed to travel, the posturing he did to live up to the example he wished to be for his fellow African Americans, and scholars’ posthumous assumptions and lack of access to factual information. This context is especially important as more of Dédé’s music is being rediscovered and published for modern performance.

You can hear a piece by Edmond Dédé performed as part of the Grant Park Music Festival’s American Salute concert on July 5. Sally McKee's book, The Exile's Song, is a fascinating read and contains much more information about the political and cultural history of New Orleans. FInd it at your local library or read it online here.