Erik Satie 100 Years After His Death: More Than Just “Gymnopedies”

Portrait of Erik Satie by Pablo Picasso (1920)

July 2, 2025, marks 100 years since the death of French avant-garde composer Erik Satie. Largely dismissed as an eccentric in his lifetime, Satie is now regarded as a pioneer of modern music, paving the way for 20th-century harmonies and musical movements such as minimalism and ambient music. Most will know his piano piece Gymnopédie No. 1, but Satie is so much more. Read on to learn more about this one-of-a-kind artist and listen to a survey of his works.

Erik (né Eric) Satie was born in the Norman coastal town of Honfleur on May 17, 1866, to a Scottish mother and a French father. His mother and baby sister died when he was only six, so he and his brother, Conrad, were sent to live with their grandparents. They enrolled him in school, and he began music lessons with a local organist. But tragedy soon struck the Satie family yet again. When Satie was 12, his grandmother mysteriously drowned during her regular swim at the local beach. After her death, he and Conrad were sent to live with their father in Paris.

The boys’ education that first year in Paris was unorthodox. Instead of enrolling in school, they audited lectures at the Collège de France and the Sorbonne and attended the theater with their father. Much to the young Satie’s chagrin, his father married a piano teacher and amateur salon composer named Eugénie Barnetche in 1879. Barnetche sought to mold Erik in her image, enrolling him in a preparatory course at the Paris Conservatoire. Thus began what Satie called “the worst seven years” of his life.

Deemed “gifted but indolent” by his tutors, Satie was not a star pupil by any means. He did not practice, and his personality was not well-suited to the sterile academic environment, which promoted technical excellence over creativity. Instead, entranced by religion and medieval history, Satie spent much of his time meditating in Notre Dame and pouring over tomes in the Bibliothèque de Paris. The gothic architecture of Notre Dame inspired Satie’s first consequential composition, Ogives (1886).

Satie eventually left the conservatory without a diploma in 1886 and enrolled in mandatory military service. The military proved an even worse fit than the conservatory. He only lasted four months into his three-year stint, as he got himself invalided out by intentionally contracting bronchitis after standing bare-chested in the winter rain.

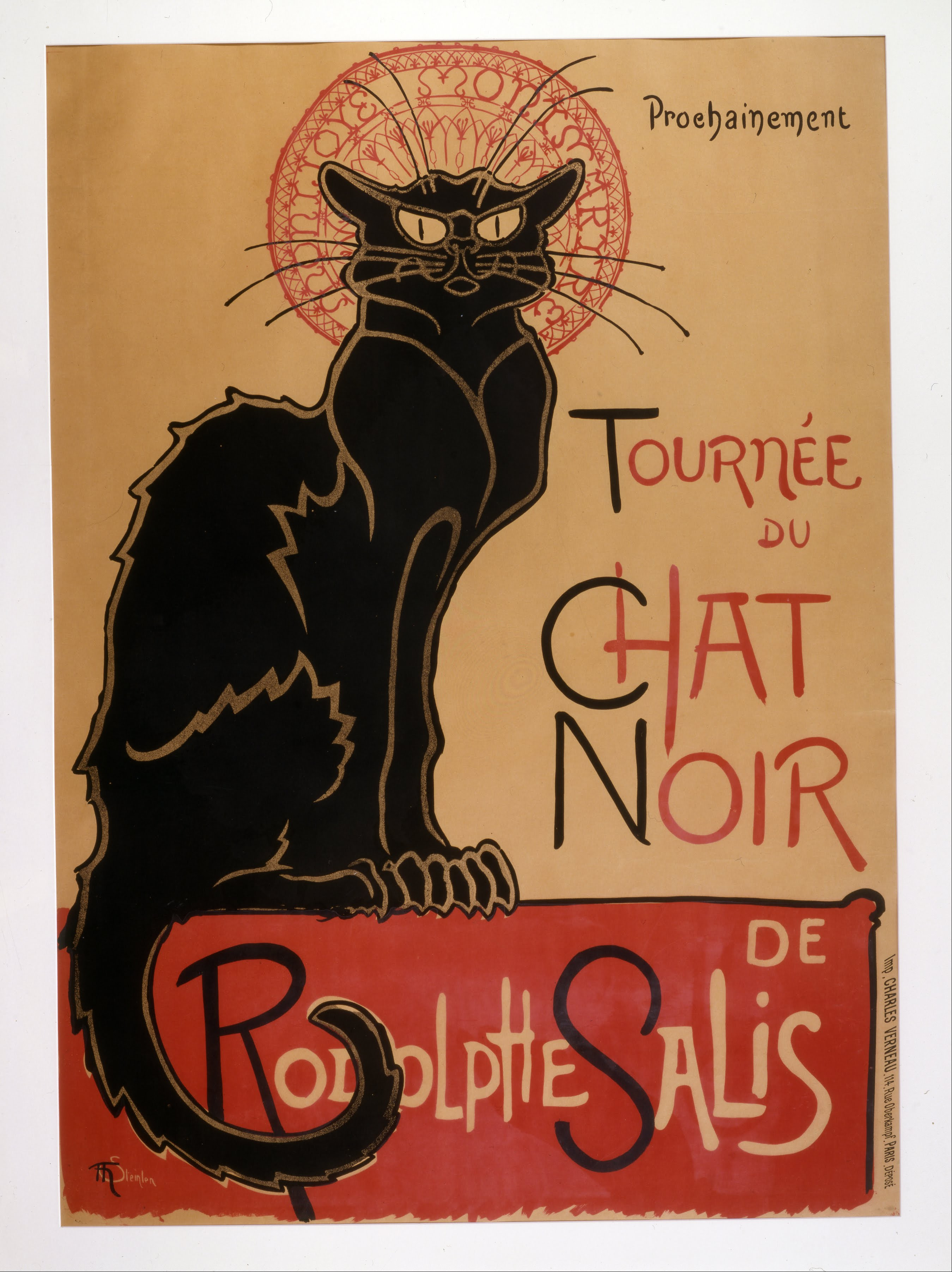

When Satie returned to Paris in 1887, he embraced la vie bohème, eking out a meager living as a café pianist in Montmartre, the city’s countercultural mecca. A new life called for a new style and public persona. So, Satie adopted the bohemian fashion of a frock coat, top hat, and long hair. One of his main haunts was the famous Chat Noir cabaret. In 1890, he became the conductor of the cabaret’s in-house orchestra, which accompanied performers and shadow puppet shows. It was during his bohemian years that he composed his most famous works, Gymnopédies (1888) and Gnossiennes (1890).

Théophile Steinlen's 1896 poster advertising a tour of Le Chat Noir's troupe of cabaret entertainers

The cafés and cabarets of Montmartre were a hotbed of creativity, frequented by intellectuals, artists, writers, musicians, and even mystics. One influential character Satie met there was the writer, critic, and Rosicrucian Joséphin Péladan. The charismatic Péladan started a Rosicrucian sect called L’Ordre de la Rose-Croix Catholique du Temple et du Graal. The artistic/religious cult attempted to marry the ideas of mysticism and Catholicism and strove for the “ideal” in both art and life to counter the “ugliness” of modernism.

To further his philosophies, Péladan mounted a series of Salons de la Rose+Croix featuring works by Symbolist artists and composers. Satie acted as in-house composer for the Rose+Croix, giving him a public venue for his music for the first time. When he fell out with Péladan in 1892 (something that would happen repeatedly with friends and colleagues throughout his life), Satie created his own sect called L’Église Métropolitaine d’Art de Jésus Conducteur. The sect boasted just one member: himself.

Satie’s so-called “Rose+Croix” period lasted from 1890 to 1895. This new period in his life again necessitated a change in style. He switched out the bohemian get-up for a quasi-religious one, complete with flowing robes and a pointy beard. Musically, Satie continued to experiment in his quest to find a perfect compositional system, playing with golden section proportions, total chromaticism, mosaic construction, and Ancient Greek modes. A major work from this period was an absurdist “Christian ballet” called uspud. When the Paris Opera declined the score, Satie challenged the impresario to a duel. This challenge forced the opera house to officially “consider” the work, which Satie took as a win, even though they declined to stage it.

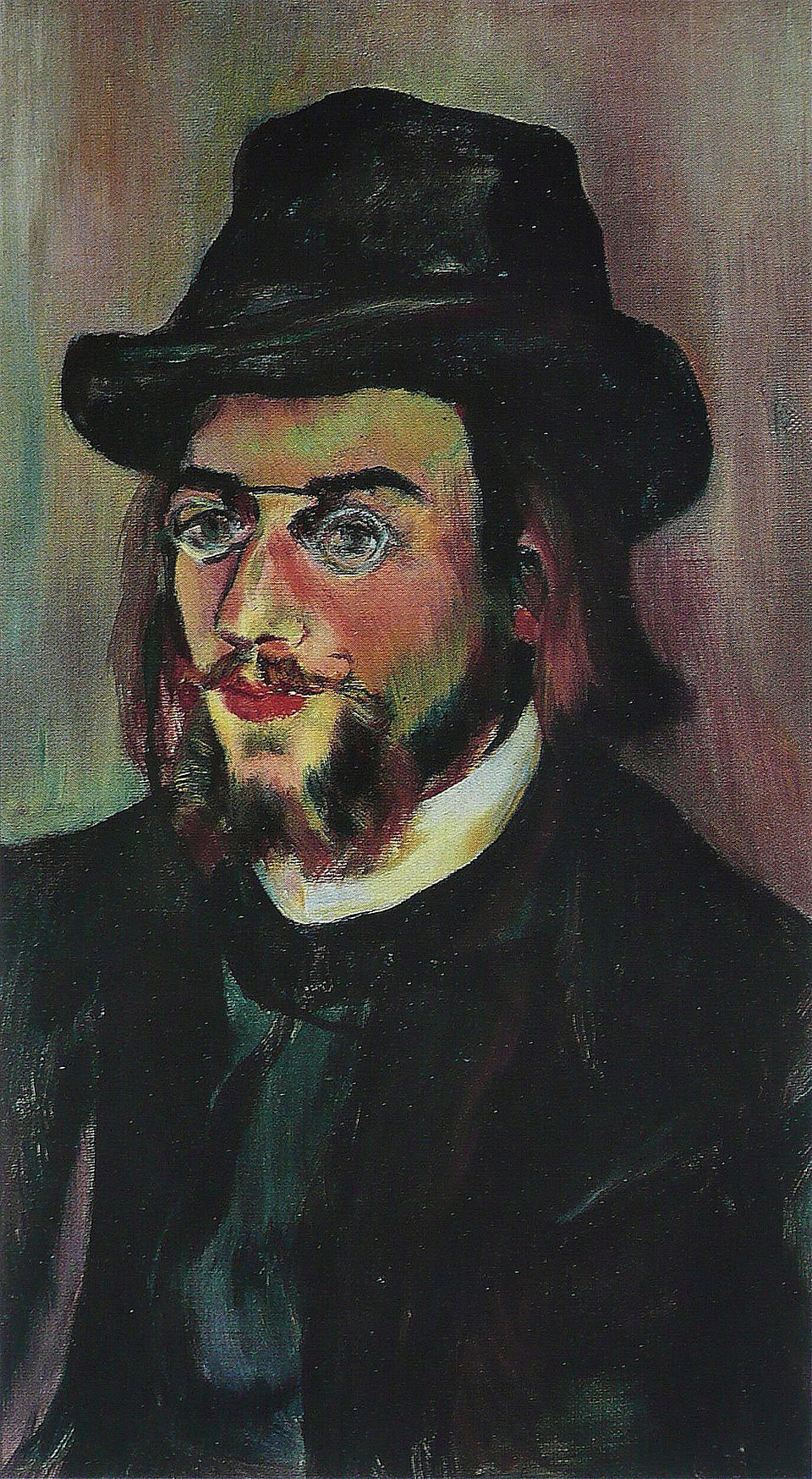

This period also saw Satie’s only known love affair—a brief but intense romance with artist Suzanne Valadon. After their dramatic breakup in 1893, Satie composed Vexations, a piece comprised of just 13 bars to be repeated 840 times. Regardless of whether Satie was serious about this instruction, the concept behind Vexations was way ahead of its time. As musicologist Robert Orledge explains, the work “is both the first organized piece of total chromaticism, on a hexachordal basis, and the first minimalist piece.”

Portrait of Erik Satie by Suzanne Valadon (1893)

In 1895, Satie bought seven identical brown velvet suits, marking the beginning of his “Velvet Gentleman” period. He hardly composed between 1895 and 1897, but Debussy’s orchestration of Gymnopédies No. 1 and No. 3 in 1897 reignited Satie’s creative energies. Even with the success of Debussy’s orchestrations, Satie was not fully accepted into the musical establishment and lived hand-to-mouth his entire adult life. In 1898, he moved to the Parisian suburb of Arcueil, where he rented a tiny one-room apartment with no running water or electricity—just a bed, a table, one chair, and a piano. He walked over three miles into the city every day to play at the cafés-concerts in Montmartre, carrying a hammer for protection and stopping off at cafés for a tipple along the way.

He formed a partnership with music-hall singer Pauline Darty in 1902, composing and arranging satirical songs for her such as “Je te veux,” “Le Diva de L’Empire,” and “Le Piccadilly.” Marking a distinct break from Satie’s usual compositional style, these straightforward diatonic songs helped popularize the syncopated American dance music that was just making its way into Paris. Even though these songs proved extremely popular with the public, Satie still considered cabaret playing to be “more stupid and dirty than anything.”

In 1903, Debussy criticized Satie for the lack of form in his works. In typical cantankerous fashion, Satie retaliated with Trois morceaux en forme de poire (“Three pieces in the form of a pear,” a “pear” being slang for a “fathead” or “fool”). The title is an obvious jab at his friend, made even more ridiculous by the fact there are seven pieces in the set instead of the indicated three. In her book on Satie, Mary E. Davis calls this work “an unorthodox anthology of Satie’s works from the 1890s,” comprising “an extraordinary compendium of Satie’s experiments and musical styles, juxtaposing lively cabaret and dance idioms with the more interiorizing and esoteric approaches” of his Rose+Croix period.

Although Satie was proud of this synthesis of “high” and “low” art, he was approaching 40 and still not where he wanted to be in his career. He finally admitted to himself, “There is a musical language and one must learn it.” Satie enrolled in composition and counterpoint classes at a music academy called the Schola Cantorum in 1905, playing in cabarets by night and composing fugal exercises by day.

He took his studies more seriously this time, feeling more at ease in the Schola’s learning environment than that of the Paris Conservatoire. Whereas the Conservatoire expected technical perfection and focused on 19th-century music, the Schola emphasized artistry and taught a broader repertoire, from medieval chant to contemporary music. Taking his musical tuition more seriously meant adopting a more serious personal style. For the rest of his life, Satie eschewed the velvet suits in favor of a more conservative costume befitting a “Bourgeois functionary,” or a civil servant.

In 1911, Satie finally got the recognition he deserved. In January, Ravel played a program of Satie’s early piano works for the newly formed Société Musicale Indépendante. After this outing, Satie came to be hailed as the “precursor” of modern French music, having anticipated the harmonic language of composers such as Debussy and Ravel a quarter century before anyone else. Satie was suddenly thrust into the public eye. High-profile performances of his works earned rave reviews, several of his older works saw print for the first time, and articles about him ran in numerous publications.

Buoyed by his recent success, Satie underwent a burst of compositional activity between 1912 and 1916. He largely focused on humoristic piano suites. Blending the esoteric and the base, these highly inventive suites toy with musical conventions. Most of the pieces, such as Embryons desséchés, lack bar lines and key signatures, and many include his own narratives and commentaries between the staves. Far beyond the traditional use of language solely for lyrics or musical directions, these texts are only there for the pianist to read and interpret as they will, whether that interpretation influences their performance or not.

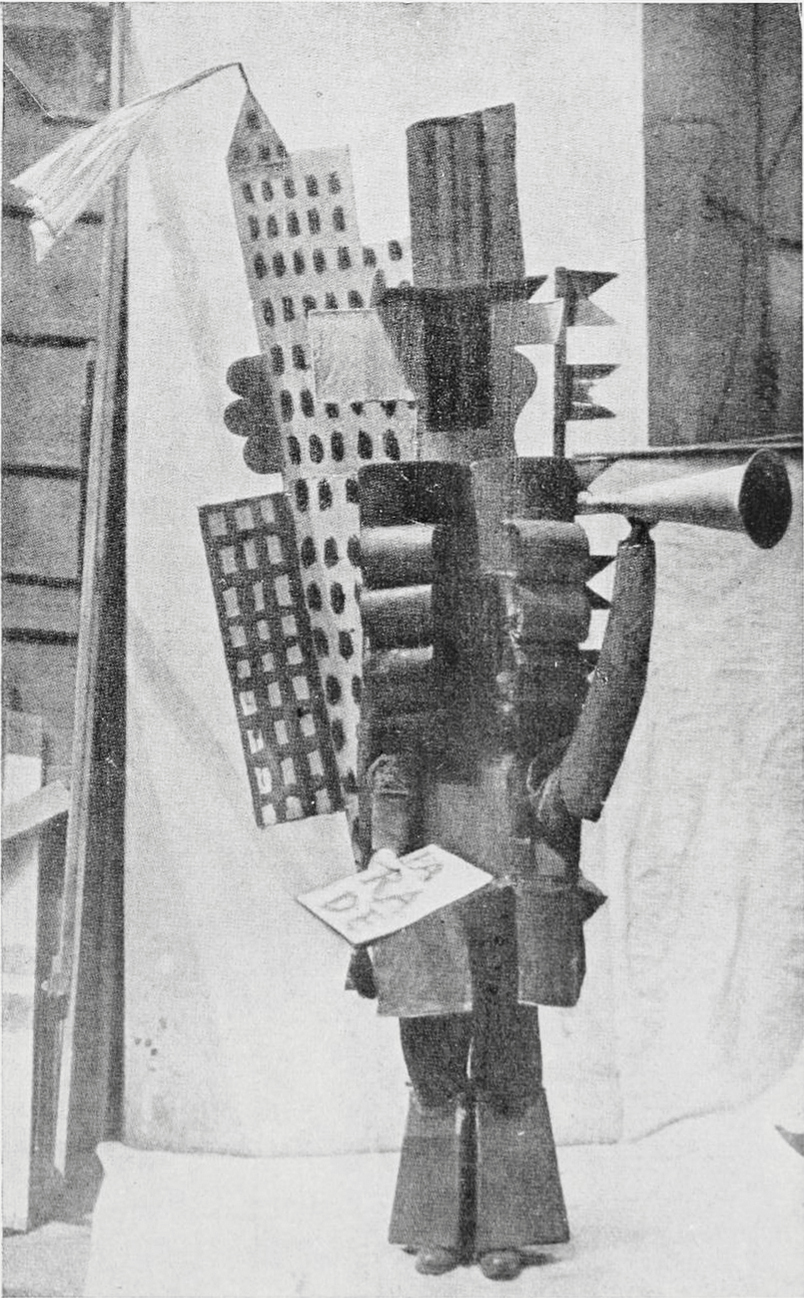

During World War I, Satie made a fruitful connection with poet and playwright Jean Cocteau. Cocteau opened up doors for Satie to high society and paved the way for his collaboration with Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes (the same company that premiered Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in 1913). The result of this collaboration was the 1917 ballet Parade, with music by Satie, scenario by Cocteau, choreography by Léonide Masssine, and cubist sets and costumes by Pablo Picasso.

Costume design by Pablo Picasso for Parade (1917)

As was the case with Rite of Spring, the premiere of Parade caused an uproar among audiences and critics alike. One of the many controversial aspects of the ballet was the score's call for unusual percussion instruments, such as sirens, a typewriter, a starter pistol, a roulette wheel, tap shoes, and a bouteillophone, or bottle xylophone. When one critic gave the ballet a bad review, Satie called him “an ass without music” (among other names that cannot be published here), leading the critic to sue Satie for libel. Satie was sentenced to eight days in prison but avoided jail time by publicly apologizing. At the trial, Cocteau, who had testified on Satie’s behalf, was beaten and dragged away by police for repeatedly shouting “ass” in the courtroom.

1920 proved to be another banner year for Satie. That year saw two festivals of his music and the first and only performance of Musique d’ameublement (“Furniture Music”) in his lifetime. Designed to be in the background, Musique d’ameublement paved the way for ambient music (and, some would say, musak) later in the 20th century. It also presented an experiment in the meaning of art. As music that is intended not to be listened to but to complement a space, like a good armchair, it questions the purpose of music as a means of expression.

Satie’s affinity for drink eventually caught up with him. In February 1925, he was taken into hospital with cirrhosis of the liver and pleurisy. He remained in the hospital until his death on July 2. Eccentric until the last, his final words purportedly were, “Ah, les vaches!” (“Ah, the cows!” or “Ah, the rascals!”). He left behind a squalid apartment full of trash for his few remaining friends to clean out. In doing so, they discovered numerous scores that had fallen behind the piano, which Satie had thought lost.

Satie’s reputation deteriorated immediately after his death, but a few composers continued to advocate on his behalf. Calling Satie “indispensable,” John Cage was among those who championed Satie’s works and ideas among the postwar American avant-garde, posing Satie as an alternative to the compositional approaches of Schoenberg, Boulez, and Stockhausen. According to Mary Davis, Satie soon came to be hailed as an “avatar of modernism” and the “progenitor of experimental art music.” In the 1960s, Satie gained popularity outside of classical spheres when the rock band Blood, Sweat & Tears adapted two of the Gymnopédies for tracks on their self-titled album in 1969. Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 1 continues to be covered and sampled in pop music to this day, especially within the lo-fi movement.