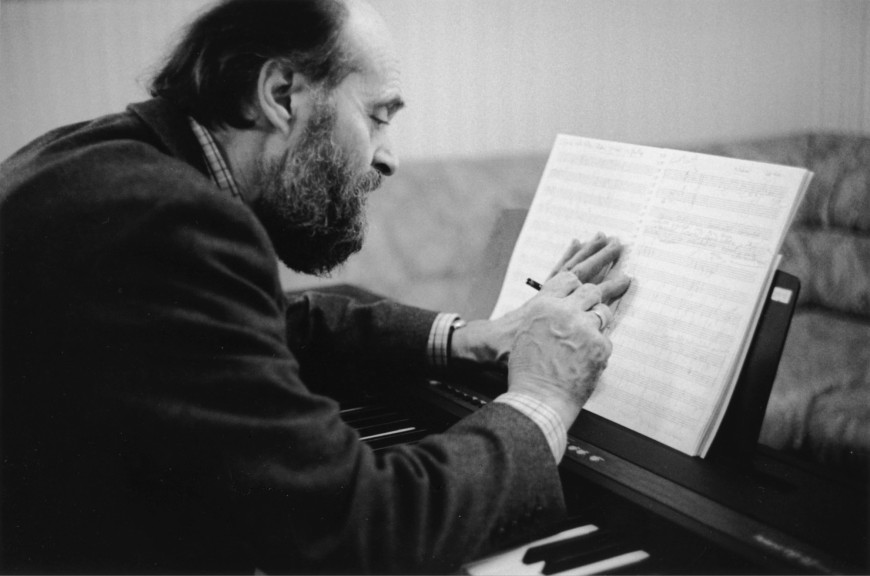

Happy 90th Birthday, Arvo Pärt

Composer Arvo Pärt, who turns 90 this month. PC: Roberto Masotti

“I could compare my music to white light which contains all colours. Only a prism can divide the colours and make them appear; this prism could be the spirit of the listener.” —Arvo Pärt

Estonian minimalist composer Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) turns 90 years old on September 11. To celebrate this major milestone, we’ve selected a few of our favorite works from his output and explain how they fit into his biography. (Click the links in the article to listen to the pieces on YouTube, or scroll down to the end of the article for a Spotify playlist.)

Pärt is one of the most prominent proponents of “holy minimalism,” an offshoot of the larger minimalist movement of the 1960s and 70s. His compositional style incorporates the traditional melodic and harmonic elements of Renaissance, Medieval, and Eastern Orthodox sacred music within the simplified framework of minimalism. However, Pärt did not always approach composition this way.

His unique compositional voice evolved out of his exploration of serialism in the late 1950s and 60s, as was fashionable at the time. During this period, his works rested firmly within the avant-garde, employing twelve-tone techniques and unusual instrumental colors and combinations. (See Symphony No. 2, which is not only based on a twelve-tone row but also incorporates several non-musical instruments, including squeaky rubber ducks and crackling sheets of cellophane.)

A turning point came in 1968 with Credo, a work for piano, choir, and full orchestra that puts Bach's Prelude in C Major (BWV 846) in a dissonant diologue with a twelve-tone row. The piece was considered an act of political defiance in its use of an overtly Christian text—something that was verboten under Communist rule in Estonia. The backlash that ensued led to nearly a decade of self-imposed creative exile. During this time, Pärt joined the Eastern Orthodox Church, discovered Gregorian chant, and immersed himself in medieval and Renaissance polyphony. In 1980, he then emigrated from Estonia to Berlin, where he could practice his religion more freely.

Pärt reemerged in 1976 with a totally new compositional style grounded in these ancient musical influences and the spareness of minimalism. However, he did not wholly abandon the strict rules that govern harmonic movement in serialism. Inspired by the Orthodox tradition of bell-ringing, Pärt created a compositional style called “tintinnabuli” (from the Latin for “little bells”), in which one voice or section arpeggiates a chord, while the other voice or section serves a more melodic function, moving in stepwise motion.

“I work with very few elements—with one voice, with two voices,” Pärt explained. “I build with the most primitive materials—with the triad, with one specific tonality. The three notes of a triad are like bells. And that is why I call it tintinnabulation.” The resulting mystical sound world is one that is both wholly modern yet timeless, as if it has existed forever.

From this stylistic breakthrough, Pärt quickly produced a series of works that would become some of his most popular. One of these is Fratres (1977). French for “brothers,” Fratres is a set of variations on a six-bar theme. It is not scored for any particular instruments but is most often heard in a version for piano and violin. It exemplifies Pärt’s tintinnabuli technique, with the piano acting as the static tolling bells and the frenetic violin taking on the role of the melody. This dichotomy captures the “instant and eternity [that] are struggling within us,” per the composer.

The following year, Pärt wrote another one of his most famous pieces, Spiegel im Spiegel, which has been used in countless films and television shows. Meaning “mirrors in the mirror” in German, Spiegel im Spiegel captures the sense of endless reflections when mirrors face each other. In this simple yet poignant piece, the piano’s ascending arpeggios toll out the slow harmonic movement, while the violin spins an achingly drawn-out melody on top.

Pärt’s “holy minimalist” style has lent itself particularly well to sacred choral music, giving him an outlet to express his religious beliefs. One notable example is Magnificat (1989). As Pärt’s biographer Paul Hillier explains, this piece “displays the tintinnabuli technique at its most supple and refined.” Here, the use of drones reinforces the sense of timelessness that Pärt establishes through lengthening and repetition.

His later works take a more flexible approach to tintinnabulism, though they are usually still governed by a strict formal design, as evidenced in In Principio (2003). Here, the first and last movements are ostensibly inverses of each other, providing a symmetrical framework. In the first movement, the choir sings the text syllabically on an unchanging A-minor chord (the “tintinnabular” part), while the orchestra interjects with chords that cycle through all twelve keys. In the final movement, these roles are reversed: the orchestra intones the persistent A-minor chord, while the choir and brass climb ever higher. The inner movements are less rigid in form and contain more melodic interest, particularly the Mozartian central movement.

Another gorgeous sacred choral work is The Deer’s Cry (2007). It sets part of the lorica attributed to St. Patrick, also known as St. Patrick’s Breastplate. A lorica (from the Latin for “armor”) is a prayer recited for protection. The story goes that in 433 AD, St. Patrick led his followers to safety by chanting the lorica. As the pagan King Lóegaire’s men lay in wait, ready to ambush them, they saw not Patrick and his missionaries but a doe followed by twenty fauns. Again, Pärt’s voice is unmistakable. He uses sparing musical material to poignant effect, with the repetition of “Christ with me” in the lower voices evoking the marching of St. Patrick with his followers.