Henry VIII: The Musician King

King Henry VIII depicted as King David, seated with harp, illustrating Psalm 52; Psalter of Henry VIII British Library, Royal 2 A. XVI, f.63v

MASTERPIECE series Wolf Hall returns to WILL-TV this fall, airing Sundays at 9 p.m. beginning October 27. Adapted from Hilary Mantel’s historical novels Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, the award-winning miniseries charts Thomas Cromwell’s rise to political power within the court of King Henry VIII. From humble beginnings as the son of an abusive blacksmith, Cromwell (played by Mark Rylance) works his way up to the role of chief minister to Henry VIII (played by Damian Lewis) during the tumultuous Protestant Reformation.

Music plays an integral role in setting the mood of the show, be it through composer Debbie Wiseman’s contemporary score featuring Tudor instruments or the integration of authentic music from the era played by the Musicians of Shakespeare’s Globe, some of which was written by Henry VIII himself. While today Henry VIII is most remembered for his six wives and founding the Church of England, he was an accomplished musician and composer and prominent patron of the arts. In this article, we’ll examine Henry VIII’s musical contributions and attempt to separate fact from fiction.

Although the legend that Henry VIII composed “Greensleeves” for Anne Boleyn has since been disproved, the Tudor king was the most prolific composer of any English monarch. (Henry V composed, as did Henry VIII’s daughter, Elizabeth I, but not to the same extent.) As the second son of Henry VII, he was not groomed for the throne but received a comprehensive education to prepare him for a career in the church. A true Renaissance man, he excelled in languages, literature, theology, sport, music, and even dance. When his older brother, Arthur, died in 1502, Henry’s path was forever altered. He was crowned king just shy of his 18th birthday in 1509.

A love of music remained a constant throughout Henry VIII’s long and tumultuous reign (1509–1547). His court flourished with cultural activity. Music played an integral role in daily life, accompanying meetings, processions, banquets, tournaments, religious services, and more. He enjoyed music of all kinds, from sacred polyphony and plainchant to secular ballads, dances, and bawdy drinking songs. The number of full-time musicians in his court totaled 58 by the end of his reign, up from just five during the rule of Edward IV. In addition to secular musicians—such as viol consorts, trumpeters, and lutenists—he employed a private household chapel choir and the Chapel Royal, which traveled with the court and included some of the finest musicians in the land.

Musicians didn’t just provide entertainment; they demonstrated Henry VIII's wealth and power to his rivals, both foreign and domestic. In fact, music became a point of contention within his own court. In 1517, Henry learned of a choir that was even better than his own Chapel Royal—that of Cardinal Wolsey, his chief advisor. In retribution, the king took for his own choir Wolsey’s star treble, a boy named Robin praised for his pure tone and ability to improvise descants. (This would not be the last thing of Wolsey’s the king would take. In 1529, he would confiscate Wolsey’s palace and all his possessions and strip him of his office for failing to secure an annulment from the Pope for Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon.)

Henry VIII wasn’t just an admirer of others’ musical talents but a competent musician himself. As one contemporary put it, he “much delighted to sing,” while another said he “plays well on the lute and harpsicord [and] sings from books at sight.” In addition to these instruments, he is said to have played the cornet, regal (a small portable organ), flute, virginals, recorder, and organ and amassed an impressive collection of musical instruments.

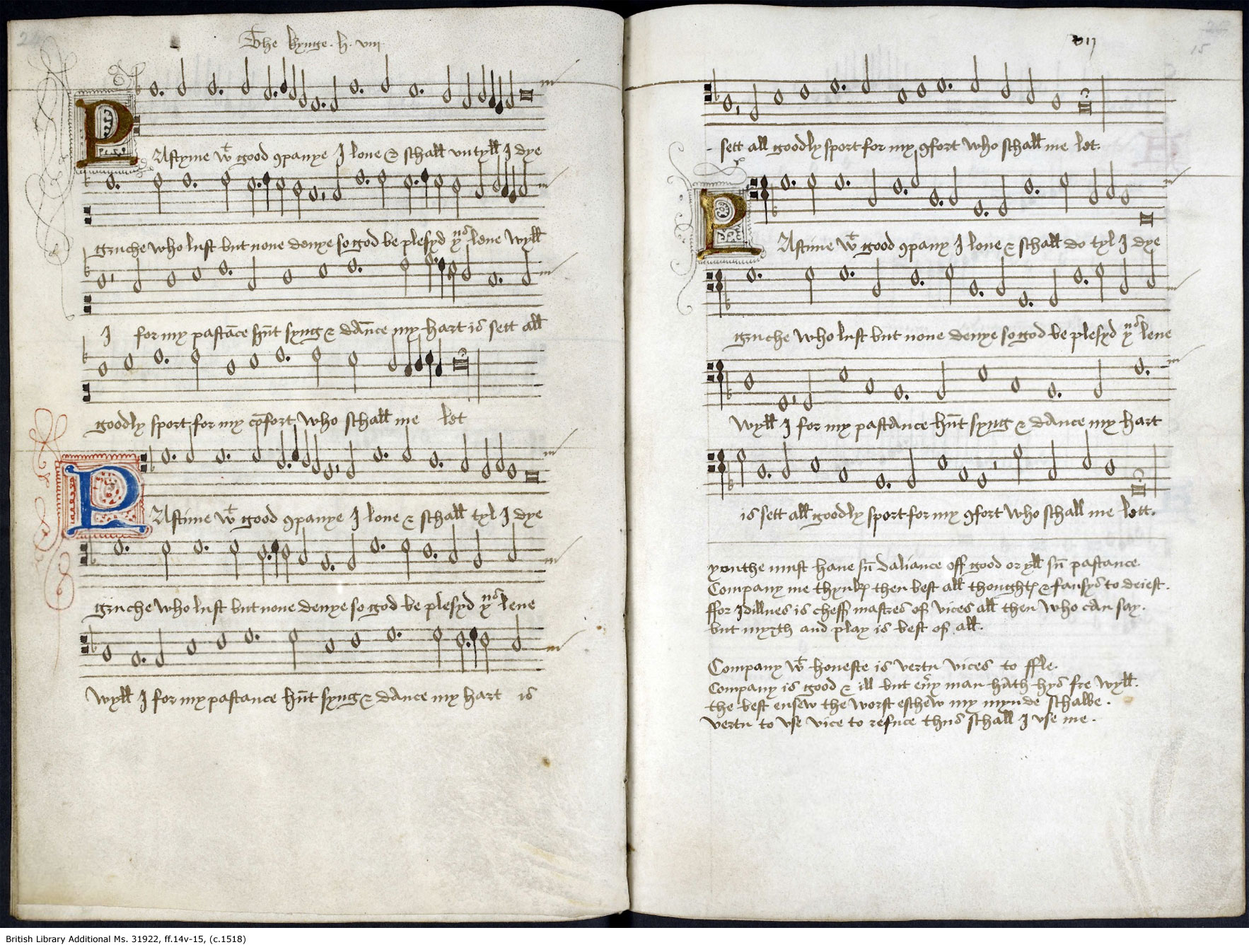

The king’s compositional legacy is preserved in a volume known as the Henry VIII Manuscript, now held in the British Library (Lbl Add.31922). Compiled around 1518, it was likely never owned by the king himself but intended for use by members of his court for amateur music-making or to educate royal children. The volume includes 109 secular songs and instrumental works by numerous English and continental European composers. But the manuscript gets its name because of the most represented composer in the collection, Henry VIII. Around a third of the pieces were allegedly penned by the king, bearing the inscription “the kynge h. viii.” Over half of these are songs for three or four voices, while the others are short instrumental numbers.

The quality of Henry VIII’s compositions is mixed. The four-part songs with French texts likely date from his early teens, only surviving due to the fame of the composer rather than any musical merit. Some of the compositions borrow musical material from other composers, which, to be fair, was a common practice at the time. Some also contain schoolboy errors such as parallel fifths and doubled thirds or clumsily written inner parts, adding creditability to the claim that they were written by the king and not works by a professional composer that he slapped his name on. However, the songs in English are more accomplished, particularly the hugely popular song “Pastyme with good companye” (shown above), as is the instrumental piece “Tandernaken,” which features on the Wolf Hall soundtrack.

Henry VIII likely composed many of these works around 1510. Upon ascending the throne, he wished to relaunch Henry V’s war against France to reclaim French lands for England. When the council denied his request (a plot point in the first episode of Wolf Hall), he secluded himself from court throughout the summer of 1510, immersing himself in amusements like shooting, singing, dancing, wrestling, playing instruments, “casting of the barre” (i.e., weightlifting), and composing. He may have penned these songs during this time of self-imposed exile.

Outside of the Henry VIII Manuscript, we know little else of the king’s compositional output. According to chronicler Edward Hall, Henry wrote two Latin mass settings for five voices in 1510, “which were sung oftentimes in his chapel, and afterwards in diverse other places.” However, no scores survive, so this cannot be verified. Only one other piece of his survives outside the Henry VIII Manuscript—a three-part sacred motet for male voices called “Quam pulchra es,” found in the Baldwin Manuscript (Lbl Roy.24.d.2).

Regardless of the musical quality of any of Henry VIII’s compositions, they help to paint a more nuanced picture of the complex figure, particularly during his younger, less despotic years. They also illustrate what courtly life was like and the musical tastes of the time. The historical importance of the author also helped preserve what little does survive, including the works of the other composers contained in the Henry VIII Manuscript, which otherwise may have been lost.

In advance of the rebroadcast of Wolf Hall later this fall, check out the show's Tudor soundtrack, Wolf Hall: The Tudor Music, available wherever you stream your music. Can’t wait until October 27 to watch the series? Friends of WILL have access to all six episodes of Wolf Hall with WILL Passport.