Music for Remembrance

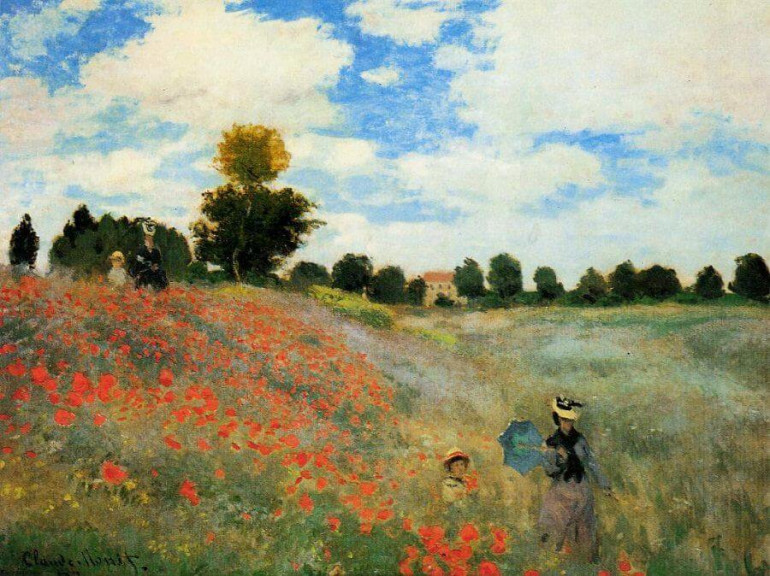

The Poppy Field near Argenteuil (1873) by Claude Monet

Composers used music in various ways to process the horrors of the First World War, then thought to be “the war to end all wars.” Some poured their grief into heartfelt elegies for lost friends, faraway homes, and shattered innocence, while others vividly captured the violence and senselessness of war through discordant music. As we honor all those who have served this Veterans Day, originally known as Armistice Day, we take a listen to some poignant responses to the First World War from composers who served or stood witness, as well as works by composers killed in action.

Gerald Finzi – Farewell to Arms

Although British composer Gerald Finzi (1901–1956) was too young and unhealthy to serve in World War I, he was deeply affected by it nonetheless. Within the span of a couple weeks, he lost his only remaining brother, Edgar, and his beloved music teacher, Ernest Farrar. Farrar died in service in France in 1918 at the Battle of Epehy Ronssoy after only being on the front for 10 days. The loss of his teacher hit Finzi especially hard, as Farrar was not only his mentor but also a close friend, Farrar being only 30 when he died. Finzi became a lifelong pacifist as a result of this crushing loss.

In the 1920s, Finzi set the first two verses of George Peele’s (1556–1596) poem “His golden locks time hath to silver turned” as an aria for tenor and small orchestra. The aria features a Bach-like ritornello in unison strings, symbolizing the inexorable march of time as the voice decries its passing. In the 1940s, Finzi found a complementary poem by Ralph Knevet (1600–1671), which made an apt introduction to Peele’s poem, as both are about soldiers laying down their arms in their old age and use the imagery of an abandoned helmet becoming a beehive. Finzi turned Knevet’s poem into a baroque-style recitative to precede the aria. Though written nearly 20 years apart, the two movements flow remarkably well together.

Frederick Septimus Kelly – Elegy for String Orchestra

Frederick Septimus Kelly (1881–1916) was a gifted athlete as well as concert pianist and composer. Australian-born Kelly came to England to study at Eton and then Oxford, where he took up rowing. He was even a member of the gold medal-winning England crew at the 1908 London Olympic Games.

As soon as war broke out in 1914, Kelly enlisted in the Royal Navy. He served with a number of close friends, including renowned wartime poet Rupert Brooke. Brooke died of sepsis from an infected mosquito bite while on a French hospital ship on its way to landings at Gallipoli in April 1915. Kelly was among the men who buried Brooke on the Greek island of Skyros. Before sending Brooke’s notebooks of poetry back to his family, Kelly copied down the contents in case they got lost in transit.

While in his tent at base camp at Gallipoli, Kelly wrote Elegy for String Orchestra in Brooke’s memory. Kelly wrote in his diary on Friday May 21, 1915: “. . . the whole of the afternoon bullets have been whistling continuously over my dug-out. I have ever since the day of Rupert Brooke’s death been composing an elegy for string orchestra . . . Today I felt my way right through to the end of it.” Kelly was wounded twice at Gallipoli, earning a Distinguished Service Cross, though he did not live to receive it. Kelly survived the slaughter at Gallipoli only to die at Beaucourt-sur-l’Ancre in the last days of the Battle of the Somme—just one of a dozen composers killed in that pivotal battle.

Ivor Gurney – "In Flanders"

Like many other musicians of his generation, British composer Ivor Gurney’s (1890–1937) musical studies were interrupted by World War I. Gurney was a student of Charles Villiers Stanford at the Royal College of Music when war broke out in 1914. He volunteered immediately but was turned down for poor eyesight. He was eventually drafted in 1915 when the army could no longer afford to be choosey. When he inhaled poisonous gas in 1917, he was sent to Edinburgh to recuperate for a month. However, the combination of the lethal gas and shell shock caused him to suffer a severe mental breakdown shortly thereafter, and he was re-hospitalized. He was eventually honorably discharged from the army in October 1918. Though he returned to his musical studies after the war under the tutelage of Ralph Vaughan Williams, his mental health continued to deteriorate. He was eventually institutionalized for the last 15 years of his life and died of tuberculosis in a mental hospital at the age of 47.

During his relatively short period of musical output, Gurney composed over 300 songs, though only about 100 of these have been published. Some of these he composed while in the trenches, though he also processed his feelings through poetry. Many of these poems and songs echo themes of longing for the beauty of his native Gloucestershire and stoically facing the possibility of death. “In Flanders” sets words by his friend from back home, poet Will Harvey. Gurney completed the song on January 11, 1917, at Crucifix Corner in Thiepval, France.

Ravel – Le tombeau de Couperin

As a young man, Maurice Ravel (1875–1937) had been exempted from conscription in the army due to his small stature at only 5'3" and 108 pounds. Nevertheless, when war broke out in 1914, the 40-year-old Ravel was determined to serve. He applied numerous times to the Air Force but was rejected for his age and a previously undiagnosed heart condition. His friend and colleague Igor Stravinsky said, “At his age and with his name he could have had an easier place, or done nothing.” But Ravel persisted. He eventually became a medical assistant and headed to the front lines in March 1916 as a truck driver in the Army Motor Transport Corps. This was a dangerous job, as he was forced to transport munitions and fuel under heavy German bombardment. He wrote, “Day and night without lights on unbelievable roads with a load double what my truck should carry. And even so I had to hurry because all this was within range of the guns.”

In September 1916, he was sent to a hospital in Paris to recover from dysentery. Ravel's mother died in January 1917 while he was still recoupoerating, sending him into a downward spiral. He was eventually discharged from the army. Soon after, he returned to a work he had begun before the war, a piano suite based on traditional baroque dance forms used by composers like François Couperin. Though titled Le tombeau de Couperin (or “Memorial for Couperin”), the piece just takes Couperin as a stylistic touchstone and instead memorializes friends Ravel lost in the war. Le tombeau de Couperin is a surprisingly upbeat work for a memorial, which Ravel justified by saying, “the dead are sad enough, in their eternal silence.” The work premiered in 1919, performed by Marguerite Long, the widow of the dedicatee of the final movement. Ravel later turned the work into an orchestral suite in four movements.

Charles Ives – Orchestral Set No. 2, “III. From Hanover Square North, at the End of a Tragic Day, the Voice of the People Again Arose”

On May 7, 1915, the British ocean liner Lusitania was torpedoed by a German submarine off the south coast of Ireland. The tragedy claimed the lives of nearly 1,200 crew and passengers, including 128 Americans, precipitating the United States’ entry into World War I. The next day, American composer Charles Ives (1874–1954) was waiting to board a train at Hanover Square in lower Manhattan when talk of the disaster spread. Workmen and fellow passengers spontaneously broke out into one of Ives’s favorite gospel hymns, “In the Sweet By and By.” This profound moment of human connection through the unifying power of music inspired Ives to compose what would become the last movement of his Orchestral Set No. 2, “From Hanover Square North, at the End of a Tragic Day, the Voice of the People Again Arose.”

The movement begins with strains of the traditional Latin “Te deum” chant in unison voices. The cinematic scene then unfolds, and we hear the chugging of the train, the cacophony of the bustling crowd, and snatches of the aforementioned gospel hymn. As writer and composer Jan Swafford puts it, Ives “paints the spontaneous musical effusion of a grieving crowd of strangers in all its raw grandeur and shared fervor. Here was a moment in Ives’s life that reaffirmed his lifelong faith in the universal human spirit beneath all music, which his father had called ‘the music of the ages.’ Hanover Square is one of his greatest and last revelations of that spirit.”

George Butterworth – Six Songs from A Shropshire Lad

George Butterworth’s (1885–1916) death is possibly one of the most tragic losses to the landscape of British music during World War I. A promising composer, he was friends with Ralph Vaughan Williams, and even travelled the countryside with him collecting folksongs. Butterworth joined up at the start of the war, sadly destroying many of his works that he deemed not yet ready for public viewing should he not return. He was wounded in action in July 1916 and awarded the Military Cross, though he did not live to receive the honor. He died shortly afterwards at the Battle of the Somme on August 5, 1916, at the hands of a German sniper. His brigade commander, Page Croft, later wrote that Butterworth was “A brilliant musician in times of peace, and an equally brilliant soldier in times of stress.”

Butterworth is most often remembered for a set of Six Songs from A Shropshire Lad, particularly as they eerily foreshadow the composer’s own sad fate. Composed between 1909 and 1911, the songs set the poems of A. E. Housman, which were written in the shadow of the Second Boer War. The set generally reflects on the themes of the fleeting nature of youth and loss. In the first song, “The Loveliest of Trees,” the narrator reflects on the transient beauty of a cherry tree and resolves not to let his youth go to waste. Next, “When I Was One-and-Twenty” bemoans the folly of youth, while “Look Not in My Eyes” laments lost love, and “Think No More, Lad” ponders how young men put themselves in harms way unnecessarily. “The Lads in Their Hundreds” evokes the scene of a jolly crowd of young men gathering at Ludlow Fair to enlist in the army, some drawn by the ladies, others by the liquor. Ultimately, however, the song anticipates their fate as they are sent off to a war from which they may not return, captured by the chilling line, “the lads that will die in their glory and never be old.” But the masterpiece of the set comes in the final number, “Is My Team Ploughing?” which presents a dialogue between the ghost of a fallen soldier and his surviving friend, who assures the soldier he has comforted his grieving sweetheart (“Is my girl happy, / That I thought hard to leave, / And has she tired of weeping / As she lies down at eve?” “Ay, she lies down lightly, / She lies not down to weep: / Your girl is well contented. / Be still, my lad, and sleep.”).