Remembering Quincy Jones

Legendary music producer, composer, and arranger Quincy Jones passed away on Sunday, November 3 at the age of 91. His prodigious musical talent, indefatigable work ethic, and ability to build relationships with top musicians across genres propelled his long and varied career. Most people will be familiar with his work as producer of Michael Jackson’s Thriller, the best-selling album of all time, and as the composer of “Soul Bossa Nova,” which later became the theme song of Austin Powers. But did you know Quincy Jones had extensive classical training with Nadia Boulanger, one of the most renowned composition teachers of the twentieth century? Read on to learn more about Jones’s classical training and how it influenced his career.

Born on March 14, 1933, Quincy Jones had a difficult childhood growing up on the south side of Chicago during the Great Depression. His father moved him and his brother to Seattle shortly after his mother was institutionalized for schizophrenia when he was seven. It was in Seattle that his path of musical discovery began. One night, he and some friends broke into a recreation center called the Armory, where he found an old upright piano. Tinkling away on the keys, Jones recalled, “I was in heaven.”

Jones became heavily involved in the music program at his high school, trying any instrument he could get his hands on. He eventually settled on the trumpet as his main instrument. He also sang in the school choir and a gospel quartet and formed his own jazz band. Music offered him solace amid a turbulent upbringing. “Music was one thing I could control. It was the only thing that offered my freedom,” he said.

Jones would frequent the jazz clubs at night and hounded the players for lessons. He and another precocious teenage musician, Ray Charles, began playing the clubs themselves. His musical education was eclectic and his appetite insatiable: “It was jazz that I loved, but anything musical would do: choirs, orchestras, school bands, blues bands, anything,” he wrote in his autobiography. He even attended an open rehearsal with Arturo Toscanini leading the New York Philharmonic, which showed him “the potential for the divine focus and collective action that forms a symphony.”

At 15, he approached bandleader Lionel Hampton with his first composition, The Four Winds Suite, an intricate instrumental piece. Hampton was duly impressed and invited him to join his band, but Hampton’s wife insisted Jones finish his education first. Jones earned several music scholarships from Seattle University and undertook advanced study in contemporary music at what is now the Berklee College of Music in Boston at age 18. Now an adult, he joined Lionel Hampton’s band as a trumpeter and later toured the world as music director, trumpeter, and arranger for Dizzy Gillespie’s band as part of the US State Department’s “goodwill” tours in the 1950s.

In Buenos Aires, Jones met Lalo Schifrin, a classically trained jazz musician who had just returned from studying with Olivier Messiaen at the Paris Conservatory. He suggested Jones also go to Paris to study with a woman named Nadia Boulanger. Jones was excited about the prospect, hoping that in Paris he would finally be allowed to fulfill his dream of writing for strings—something that was seen as “too sophisticated” for Black music arrangers at the time.

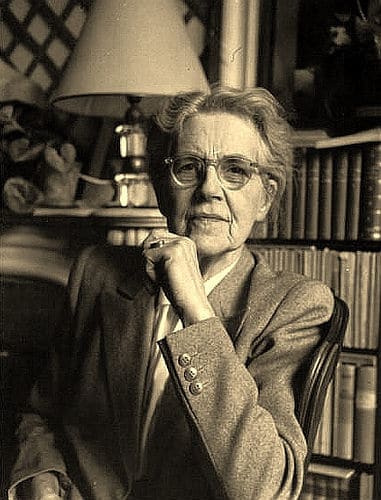

In 1957, Jones accepted a job as music director, arranger, and conductor for Barclay Records in Paris, writing arrangements for the label’s 55-piece orchestra. He was also accepted into Nadia Boulanger’s studio. Nadia Boulanger (1887–1979) was one of the most influential music teachers in history. As one of the founding members of the American Conservatory in Fontainebleau, she taught many of the greatest American composers of the twentieth century, including Aaron Copland, Virgil Thompson, Walter Piston, Philip Glass, and Elliott Carter. She was also a trailblazing composer and conductor, credited as the first woman to conduct numerous symphony orchestras, including the BBC Symphony, Boston Symphony, and Philadelphia Orchestra.

Nadia Boulanger / The American Library in Paris

Boulanger was picky about whom she taught and put prospective students through a rigorous audition process. Students had to not only demonstrate advanced analytical and compositional skills but also articulate what they hoped to gain from studying with her. Calling her “the most astounding woman” he had ever met, Jones got along very well with Boulanger despite their vastly different backgrounds, connecting over their strong work ethic, musical curiosity, and determination in the face of gender/racial barriers.

Boulanger taught Jones counterpoint, theory, harmony, music history, analysis, and orchestration, giving him a grounding in the fundamentals of Western classical music and expanding his musical horizons (including introducing him to Igor Stravinsky). As Clarence Bernard Henry writes in his biography of Jones, studying with Boulanger “gave Jones artistic validation of being a serious composer and arranger.” In addition to formal classes, they would sit in her living room and chat about music for hours. “No pencil. No paper. No lesson. Just knowledge,” Jones recalled.

Boulanger’s greatest strength as a teacher was developing her students’ talents while encouraging them to find their own paths in music and retain their unique compositional voices. When Jones wanted to try his hand at writing symphonies, she said, “Learn your skills but forget about great American symphonies. You already have something unique and important. Go mine the ore you already have.”

Boulanger’s influence on Jones, both as a musician and a person, was immeasurable. His autobiography is peppered with pearls of wisdom from his Parisian mentor. She instilled in him five essential qualities that every artist must strive for, no matter the musical genre: “Sensation, feeling, belief, attachment, and knowledge.” She also stressed the importance of having rich life experiences, saying, “Your music will never be more or less than you are a human being.”

Jones took these lessons with him throughout all the stages of his long and varied career, whether he was scoring films, arranging songs for Frank Sinatra, or producing pop albums. In particular, her advice that one can only find artistic freedom by setting boundaries and parameters helped him when he was composing film scores at a frenetic pace in the 1960s and 70s. “When you have total freedom, you automatically create chaos,” he wrote. “As a jazz artist, this was hard to swallow until I had to score films on deadline.”

Jones was an innovative film composer, among the first to integrate jazz, classical, big band, funk, Latin, techno, and other styles into his scores. His film scores reveal his training with Boulanger and the influences of Ravel and Stravinsky, his two favorite composers. This is nowhere more apparent than in the score to the 1969 Western MacKenna’s Gold, which is rich in diverse instrumental textures and timbres, dissonant harmonies, and vibrant string and horn writing.

Fellow composer and arranger Benny Carter is quoted as saying, “Quincy’s a guy whose success actually overshadows his talent.” With 28 Grammy Awards and over 2,900 songs, 300 albums, 1,000 compositions, and 51 film/television scores to his name, it is perhaps easy to take Jones’s musical talent, adaptability, and hard work for granted. Hopefully, this look into one aspect of his eclectic training gives us better insight into this musician who accomplished so much across so many different genres.

Tune into WILL-TV on Tuesday, December 31 at 10:30 pm for Quincy Jones: A Musical Celebration in Paris. Filmed in front of a capacity crowd at AccorHotels Arena, the special brings together nearly 100 world-class musicians, including a symphony orchestra conducted by Jules Buckley and a line-up of special guests.