Violin-Playing Sleuth Returns to Passport in “Sherlock”

Benedict Cumberbatch as Sherlock Holmes in MASTERPIECE series Sherlock

Award-winning MASTERPIECE series Sherlock is back on WILL Passport! Set in contemporary London, Sherlock is the modern and quirky spin on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's classic detective stories. Friends of WILL get exclusive early access to stream and binge all four seasons via the PBS app ahead of the series' rebroadcast on WILL-TV later this year. Read on to learn how the violin helps construct the character of the famous detective in the stories and contributes to the emotional storytelling in the television series.

Sherlock Holmes is perhaps the most famous violin-playing literary character of all time. Almost as distinctive as Holmes’s deerstalker hat and Calabash pipe is his Stradivari violin. Surprisingly, of this quintessential image of the perceptive sleuth, only the violin appears in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s original stories. (The hat and pipe stem from illustrations by Sidney Paget of Doyle’s stories published in The Strand Magazine between 1891 and 1904, enduring thanks to countless screen adaptations.)

In the first Sherlock Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet (1887), we learn of Holmes’s affinity for the violin as he attends a concert given by real-life violin virtuosa Wilhelmina Norman-Neruda, whose “attack and bowing are splendid,” he says. Later, in The Red-Headed League (1891), Holmes and Dr. Watson attend a concert by another historical figure, Spanish violinist Pablo de Sarasate. During the concert, Dr. Watson describes Holmes as “wrapped in the most perfect happiness, gently waving his long, thin fingers in time to the music.”

The detective’s passion for music paints him as culturally sophisticated but also eccentric as he talks at length about Niccolò Paganini and the superiority of the trees of Cremona in manufacturing violins. This enthusiasm evidently wears on Dr. Watson, who describes in The Adventure of the Cardboard Box (1892) how Holmes would “talk of nothing but violins, narrating with great exultation how he had purchased his own Stradivarius” for the unlikely low price of 55 shillings from a pawnbroker in Tottenham Court Road.

Holmes’s ability as a player is up for debate. His skills are represented in contradictory terms in the few references to his playing in the stories. In A Study in Scarlet, Dr. Watson says of Holmes, “His powers upon the violin . . . were very remarkable but as eccentric as all his other accomplishments.” He goes on to explain how Holmes could play difficult pieces at Dr. Watson’s request, but left to his own devices, the detective preferred to “close his eyes and scrape carelessly at the fiddle which was thrown across his knee.”

Dr. Watson continues, “Sometimes the chords were sonorous and melancholy. Occasionally they were fantastic and cheerful. Clearly they reflected the thoughts which possessed him, but whether the music aided those thoughts, or whether the playing was simply the result of a whim or fancy was more than I could determine. I might have rebelled against these exasperating solos had it not been that he usually terminated them by playing in quick succession a whole series of my favourite airs as a slight compensation for the trial upon my patience.”

Dr. Watson describes Holmes’s musical ability in a more flattering light in The Red-Headed League (1891), calling him “an enthusiastic musician, being himself not only a very capable performer, but a composer of no ordinary merit.” Holmes’s musical talents are one manifestation of his brilliance, whether he is composing, playing repertoire, or using improvisation to work through detective puzzles.

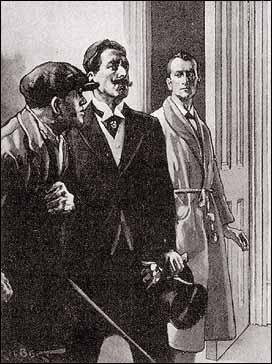

The only story in which Holmes’s violin playing is crucial to the plot is The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone (1921). In the story, Holmes pretends to go into the next room to play Offenbach’s Barcarolle while his adversaries, who have come to kill him, discuss whether they will take Holmes’s deal and give up the jewel they have stolen in exchange for their freedom. Unbeknownst to them, Holmes puts on a gramophone recording of the Barcarolle instead and hides behind a curtain so he can hear them discuss their plot to double-cross him.

Illustration for "The Adventure of the Mazarine Stone"

Credit: Alfred Gilbert, The Strand Magazine, 1921The violin does not otherwise factor into the plots of the Holmes stories. Nonetheless, it is crucial in painting the detective’s complex character. In her article “The Adventure of the Stradivarius: Violins in the Work of Arthur Conan Doyle and William Crawford Honeyman,” scholar Rachel Durkin argues, “Holmes’s conventional mastery of the violin, combined with an apparent taste for weird and even discordant sounds, expresses both his intuitive understanding of the conventional world, and his ability to move outside it.”

The late 19th century saw an increased fascination with the violin, both as a collectible object of financial and cultural value and as a popular mode of British domestic music-making, made more accessible through the advent of mass production techniques. Thus, Holmes, as an amateur player and avid consumer of classical music, is placed firmly within his culture and the middle class. At the same time, his eccentric way of playing puts him outside this sphere and in contrast with the typically masculine and staid Dr. Watson.

The violin also adds depth to the cerebral character of Holmes, whom Doyle likens to Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine, the first successful automatic calculator. While Holmes’s intense interest in the instrument’s provenance furthers the analytical and emotionally detached aspect of his character, his violin playing allows him to express his humanity in a way he otherwise cannot verbalize, giving us a glimpse into his hidden intellectual and emotional world.

Screen adaptations, particularly the Sherlock series for MASTERPIECE, have latched onto this musical storytelling device more than Doyle ever does in his writing. For instance, in the first episode of Season 2, “A Scandal in Belgravia,” we find Sherlock (Benedict Cumberbatch) playing the violin on four separate occasions—more than in any other episode. This episode marks a turning point in Sherlock’s emotional development. In Season 1, the caustic detective has no time for emotions or relationships, as they would only cloud his judgment. But in Season 2, he seems to begrudgingly open himself up to others, notably his assistant, John Watson; landlady, Mrs. Hudson; and the dominatrix, Irene Adler. (Warning: spoilers ahead.)

While Mrs. Hudson asks John, “How will we ever know what goes on in that funny old head?” Sherlock’s violin playing throughout the episode offers some clues. First, he plays “We Wish You a Merry Christmas” for Mrs. Hudson during a Christmas party at 221B Baker Street—a kind gesture with no motive other than to make her happy. Later, the extent to which Sherlock cares about Mrs. Hudson’s well-being and how much he trusts her is revealed when she is attacked by American agents.

But he hasn’t made a complete about-face. When morgue worker Molly Hooper arrives at the Christmas party in a skin-tight dress and present in hand, he thoroughly embarrasses her by deducing she must be meeting a boyfriend with whom she is wildly in love, not realizing the present is for him. He offers her a sincere apology and kiss on the cheek, indicating some growth.

Later in the episode, it appears as if Sherlock might have romantic feelings toward Irene Adler, the dominatrix who outwitted him. When he believes her to be dead, Sherlock turns to composing, which he says helps him think as he tries to crack her phone passcode. The original tune he plays is remarkably melancholy and tender. This composition becomes a recurring theme for Miss Adler in the soundtrack, resurfacing at key moments of emotional intensity.

When it eventually comes to light that Irene Adler is not, in fact, dead, John asks Sherlock if he thinks he will ever see her again. Sherlock responds by playing “Auld Lang Syne.” As well as ringing in the new year as the bells toll outside, the song can be interpreted as both a farewell to her and a tribute to his friendship with John. (“Should auld acquaintance be forgot and never brought to mind…”)

To what extent Sherlock feels, and whether such feelings would impede his brainpower, is a recurring theme in the episode. In fact, it is precisely her heart that is Irene Adler’s downfall. While other characters speculate on this question, the music gives the viewer subtle clues into Sherlock's inner life. So, be sure to watch Sherlock on WILL Passport via the PBS App or when it airs later this year on WILL-TV, and keep an ear out for the role of music in the emotional storytelling of the series.