Who Was Louise Farrenc?

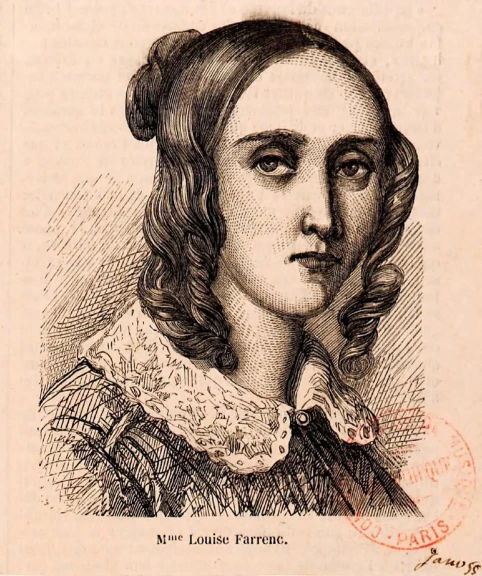

French composer Louise Farrenc (1804–1875) The History Collection/Alamy

Born into a family of renowned artists, French composer Louise Farrenc (1804–1875) demonstrated musical talent from an early age. By her early teens, she was already a professional-caliber pianist, and she began composition lessons with Anton Reicha at the Paris Conservatoire at 15. Because women were still barred from studying composition comprehensively at the institution, these lessons were private. When she married flautist Aristide Farrenc at 17, she took a brief hiatus from her studies while they toured France giving concerts. When they returned, the couple established a successful publishing house, Éditions Farrenc, and she resumed her studies.

Naturally, her earliest published works were piano pieces, including an influential collection of 30 Études that later became required study for piano students at the Conservatoire. She made her first foray into orchestral composition in 1834 with two orchestral overtures. She followed these with three symphonies in the 1840s, including Symphony No. 1 in C minor. Her turn to orchestral music was surprising, not least because women composers at the time often stuck to smaller-scale works such as songs and salon pieces for piano, but also because the forms in which she composed were of German extraction. In Germany, Beethoven’s symphonies had elevated instrumental music above all else, whereas in France, opera still reigned supreme. In addition, Farrenc’s compositional style naturally gravitated toward a more Germanic sound as a student of Reicha—a Bohemian composer trained in Bonn and Vienna and an expert on Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven—which further alienated her from the French market.

Nonetheless, Farrenc achieved success and broke barriers as a composer, teacher, and scholar. In 1842, she was appointed professor of piano at the Conservatoire—the only woman to hold a permanent chair of this rank at the Conservatoire in the 19th century. Though her orchestral works were never published during her lifetime, they saw performances across Europe. Her most notable compositions were chamber works. Her Nonet op. 83 even gained her sufficient recognition that she was able to demand pay equal to that of her male colleagues at the Conservatoire. Her largest scholarly contribution was compiling and editing a 23-volume anthology of keyboard music spanning the 16th to 19th centuries. Working alongside her husband on this project until his death in 1865, Farrenc finished the final 15 volumes as sole editor a year before her death and published a manual on historical performance practice.

Unlike Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn, Farrenc was not connected to a famous male composer by birth or marriage, which is partly why she fell into relative obscurity until recently. However, she made a unique mark on music history as a pioneer of early music scholarship and by keeping French instrumental music alive.

You can hear the University of Illinois Symphony Orchestra play Farrenc's Symphony No. 1 in concert on Thursday, November 16 at 7:30 p.m. in the Foellinger Great Hall at the Krannert Center for the Performing Arts. Other works on the program include Samuel Coleridge-Taylor's Ballade for Orchestra, Carl Nielsen's Flute Concerto, and Nokuthula Ngwenyama's Primal Message for String Orchestra.