400th Anniversary of William Byrd

This year marks a major milestone for one of England’s greatest composers. William Byrd (c. 1540–1623) died four hundred years ago on July 4, 1623. Described in 1607 as “Brittanicae Musicae Parenti” (“Parent of British Music”), William Byrd was a composer, musician, teacher, and entrepreneur of singular stature. Though today Byrd is most remembered for his sacred choral music, he mastered and advanced nearly every genre available to him at the time, including keyboard music, instrumental ensemble music, consort songs, and secular part songs. The nearly 600 pieces of his that survive demonstrate Byrd’s unique ability to blend heady musical sophistication with emotional depth. Scroll to the bottom of this article to listen to a playlist of some of Byrd's greatest works while you learn more about this fasicnating composer.

Byrd’s Catholic faith at a time when Catholic worship was illegal adds another dimension to his music and has spurred modern fascination with his life. As a recusant Catholic serving a Protestant monarch in reformed England, Byrd was in a precarious position to say the least. So it is especially remarkable that he was unwavering in his beliefs and had the audacity to publish them in musical form at a time when many of his fellow Catholic were being attacked for their faith. But Byrd remained largely shielded from religious persecution due to his powerful patrons—Queen Elizabeth I most notable among them. Nonetheless, the anxieties of being on the “wrong” side of the religious divide deeply affected Byrd’s life and music.

Curiously, Byrd was by all accounts not born into a Catholic family, but he came to his faith on his own terms. As Byrd biographer John Harley explains, “The personality revealed by Byrd’s music suggests that, given his gift of faith, he might have been drawn to Catholicism as a comprehensive intellectual system, informed by emotion and supported by tradition—a framework within which all aspects of life found a place.”

Byrd was born to a middleclass family in London sometime in late 1539 or 1540 (no birth or baptismal records survive). His older brothers, Symond and John, were choristers at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Though not much is known about his early life and musical education, the prevailing theory is that William Byrd was a chorister in the Chapel Royal, a group of priests and musicians that traveled with the royal household to attend to their spiritual needs and show off the wealth and creative talents at the monarch’s disposal. At this time, the Chapel Royal usually consisted of twelve boy choristers and twelve “Gentlemen,” one of whom acted as Master of the Children, who was responsible for the training and care of the choristers. Boys generally entered the choir at age seven and received both academic and musical training.

Though the Chapel Royal did not list the names of the choristers on its roster, Byrd is known to have studied under Thomas Tallis, who was a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal and served as organist. (Tallis, having no children of his own, took Byrd under his wing as a sort of father figure, and the two formed a lifelong friendship, with Tallis even serving as godfather to one of Byrd’s sons.) Byrd likely stayed on with the Chapel Royal after his voice broke and became Tallis’ assistant in playing the organ and rehearsing the choir. If this theory is true, Byrd would have been a chorister during the reigns of King Edward VI (1547–53) and Queen Mary (1553–8) and may have been present for Queen Elizabeth I’s coronation. Perhaps it was during the Catholic Queen Mary’s reign and her ultimately short-lived restoration of Roman Catholicism that Byrd’s faith solidified. In any case, it would have been where he was introduced to Catholic liturgical music.

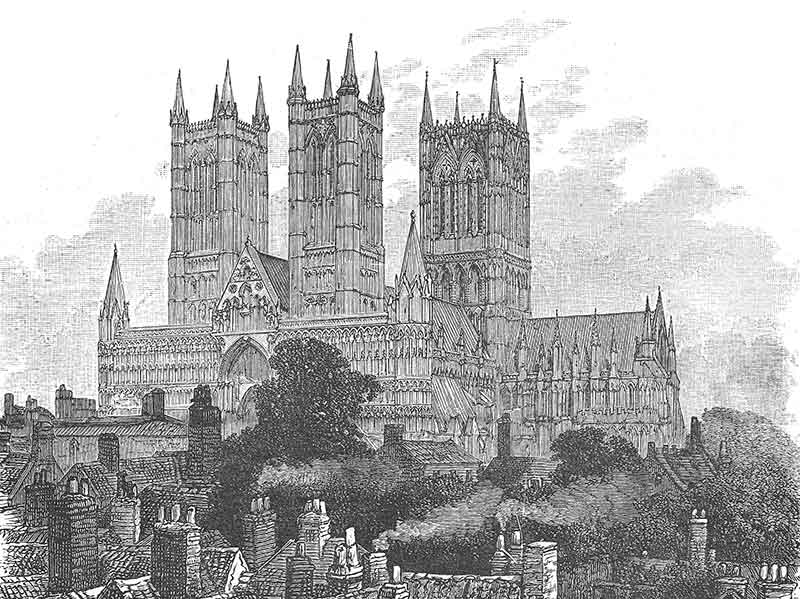

Lincoln Cathedral

What we do know for sure is that Byrd accepted the post of Organist and Master of the Choristers at Lincoln Cathedral in 1563, which came with a generous salary and residence. He began his tenure at a time when the future of church music in Britain was uncertain. Though the Queen generally encouraged music in church as long as it was not too ostentatious, Byrd ultimately came to blows with the Archdeacon and Chapter as increasingly Puritanical musical strictures were put into place. Elaborate melismatic polyphony was out in favor of simpler syllabic settings of English texts, and accompanied singing was now verboten. Many cathedrals even dismantled their pipe organs. Luckily, Lincoln’s organ remained intact, but Byrd was only allowed to give the choir their starting pitches during anthems.

Looking at Byrd’s florid keyboard fantasias that date from this period, it comes as no surprise that he broke the rules. In 1569, the Chapter suspended his salary for eight months, likely due to overly elaborate organ playing. Nevertheless, he continued to experiment privately in his keyboard compositions, and he even wrote some Latin motets, which were published later. Most of his Anglican sacred music stems from this time, and he dutifully mastered each category, from preces and psalms to simple and festal services. Around 1571, he started copying down some of his works to compile a kind of portfolio, likely with an eye to scoring a job in London where he would have more creative freedom.

That chance came in 1572 when he was sworn in as a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal as a joint organist with his old mentor, Thomas Tallis. Over the next two decades, he came into contact with powerful Catholic figures within the English aristocracy, who became his closest associates and patrons. It was also during this time that the Queen became one of his most important benefactors. In 1575, she granted Byrd and Tallis an exclusive royal patent for publishing music and lined music paper—an industry that had not yet found a foothold in England but was flourishing on the continent. The two composers published Cantiones, quae ab argumento sacrae vocantur (“Songs, which by their argument are called sacred”). The volume of 34 Latin motets—17 by each composer in honor of the Queen’s 17 years on the throne—bears a flowery dedication to the monarch, which acted as insurance against any charge of disseminating music that could be deemed too “popish."

Gentlemen of the Chapel Royal from William Camden’s sketches of Queen Elizabeth I's Funeral, 1603, British Library, Add MS 35324, f.31.v

Despite the Queen’s enthusiasm for the publication, it was a commercial failure, perhaps for its overtly Catholic flavor. In a demonstration of Byrd’s gutsiness both as a composer and as a businessman, he complained to the Queen that the patent she had granted them was a source of little profit and asked for compensation for the money he had lost in the venture. She obliged and granted him the lease for a manor in Gloucestershire—evidence of her high regard for the composer.

The next two decades saw some of Byrd’s most productive years and daring work. Undeterred by his previous publishing failure, he produced two further volumes of Cantiones sacrae in 1589 and 1591 and multiple collections of consort songs, secular part songs, and keyboard music. But this period also marked a turbulent time for him personally. Sectarian conflict heightened in the 1570s when Pope Pius V excommunicated Queen Elizabeth I and called upon English Catholics to rise up and depose her. English authorities increasingly regarded Catholics with suspicion and began to enforce recusancy laws more strictly and with steeper fines. (The Act of Uniformity, which had been passed after the Queen’s accession to the throne in 1558, required all subjects to attend Anglican church services once a week on pain of spiritual censure and fines that increased with subsequent infractions; those who refused to attend Anglican services were called “recusants.”) In addition, the Queen’s intelligence services conducted raids against suspected recusants, including many of Byrd’s closest associates. Some of those arrested were even found with Byrd’s Catholic liturgical music in their possession.

We do not know when Byrd became a Catholic or whether his wife, Julian, was already a Catholic when they married in 1568. However, their close association with known Catholics indicates they were at least sympathetic to their plight if not already Catholic while at Lincoln. Julian was first cited for recusancy in 1577, while her husband somehow managed to avoid citation until 1584, perhaps because his presence at services as part of the Chapel Royal counted as attendance. Still, his house was searched in 1585, and Julian repeatedly failed to appear in court after numerous indictments, causing her to be “outlawed” in 1586/7, which placed her outside the protection of the law.

Throughout the 1580s, Byrd is known to have attended clandestine meetings with Jesuits and supplied music for secret services in the Catholic underground. He may have even harbored Jesuits or other fugitives or offered monetary support. Byrd was likely privy to Catholic intrigues, but there is no evidence that he supported the faction that wanted to install Mary Queen of Scots on the throne. Regardless of the extent of his involvement or sympathies, he kept dangerous company in the 1580s. That said, Byrd’s loyalty to the Queen was never called into question. The Queen ultimately remitted his recusancy charges and halted his prosecution for Catholic activities in 1592 with a direct order, though this would not mark the end of the charges against him or his family.

The anxiety of this turbulent time stoked the fires of his creativity, particularly in the genre of the Latin motet. These Latin motets were more than likely intended for domestic use in Catholic residences and represented penitential meditations, outbursts, or protests on behalf of the Catholic community. There was little opportunity for these pieces to be performed in Anglican churches, particularly given the texts Byrd or his patrons chose, which could easily be read for double meaning. For instance, lamenting for Jerusalem at the time of Babylonian captivity is a recurring theme that could be a metaphor for Catholic persecution (see "Civitas sancti tui").

When recusancy laws tightened yet again in the mid-1590s, Byrd and his family moved out of London to a large property the Queen leased him in Essex. The property was near Ingatestone, which was a safe haven for Catholics, who worshiped there largely without disturbance. Although he had ostensibly retired from full participation in Chapel Royal affairs, Byrd continued to compose and publish his music, focusing his energies on music specifically for Catholic services. In a bold move, he published three Latin Mass settings for three, four, and five voices. No Mass had been composed in Britain for some thirty years, and Byrd was among the few remaining composers to remember singing them as a boy. Though these Masses were published without title pages, Byrd’s name appears on the top right-hand corner of every page, indicating that he felt secure in the protection afford him by his influential patrons. His other passion project in semi-retirement was a collection called Gradualia (1605–7), which contained music for all major feasts of the Catholic church year. Though this was not without its risks, he received permission to publish Gradualia from the Bishop of London. As evidenced by his Masses and Gradualia, his musical style became more restrained and concise by virtue of the pieces' liturgical context.

In addition to sacred music, Byrd is credited with raising the stature of English song through his extensive repertoire of consort songs. Some of Byrd's consort songs would have been written for the royal court, putting him in intimate contact with the Queen and her courtiers. Other consort songs may have been written for the same patrons who commissioned his sacred motets. The last music Byrd published was a songbook titled Psalmes, Songs, and Sonnets (1611), which contained jubilant full anthems in English, mournful verse anthems, fantasias for viol consort, and madrigal-like songs for three to five voices (see "The Eagle's Force").

Byrd died on July 4, 1623 at his home in Essex. In his will, he expressed his wish to be “honestly buryed” (meaning according to Catholic rites) next to his wife. He was likely buried in the graveyard of the local parish at Stondon Massey, though as a Catholic he was not allowed a grave marker, so his final resting place has not been located. Upon his death, the Cheque Book of the Chapel Royal listed Byrd as a “Father of Musick,” meaning he was the longest-serving member of the Chapel at that time, as he was still on the payroll until his death.

As time passed and tastes changed, much of Byrd’s music fell into obscurity, except for a few pieces that were memorialized in collections of sacred music after his death. The rehabilitation of his reputation began in 1840 when the newly founded Musical Antiquarian Society published some of his works. Editions in the early 20th century of the collected works of William Byrd laid the foundation for modern scholarship and have brought Byrd’s work back into the core of the English choral repertoire.

Though many of the details of Byrd’s life will remain a mystery given the lack of any surviving personal belongings or letters, the best window into the man’s soul is through an examination of his music. Take a listen to the playlist below for a survey of the wealth that is Byrd’s musical catalogue. Also, check out Byrd Central, a website devoted to the composer and his 400th anniversary. There you can find more information, recordings, educational resources, Byrd merch, and stories from prominent musicians whose life and work have been influenced by William Byrd.

1. Laudibus in sanctis dominum (c. 1582–91) – Magrigalian motet that opens Cantiones sacrae (1591)

2. Ave verum corpus (c. 1605) – Intimate Latin motet from Gradualia (1605) for private devotional use

3. Sing Joyfully (c. 1590s or early 1600s) – Among the last pieces Byrd wrote for the Chapel Royal that may have been a tribute to King James I (1603–1625) given the emphasis on the name “Jacob”

4. Lord Willoughby’s Welcome Home (late 1580s) – From My Ladye Nevells Booke (1591), a collection of music for the virginal, a plucked keyboard instrument

5. Mass for 4 voices: Agnus dei (1592–3) – Profoundly simple setting of the Latin Mass

6. Haec dies (c. 1582–91) – Another magrigalian motet from Cantiones sacrae (1591)

7. Ye Sacred Muses (c. 1585) – Poignant elegy for Thomas Tallis, Byrd's mentor and lifelong friend, who died November 23, 1585

8. Quomodo cantabimus (c. 1584) – Response to eight-voice motet Byrd received from Flemish composer Philippe de Monte ("Super flumina Babylonis")

9. If Women Could Be Fair (c. 1588) – Consort song from Psalmes, Sonets, and Songs of Sadnes and Pietie (1588); most consort songs were written for a single solo voice and four viols, though sometimes words were added to the viol parts to create part songs

10. Fantasia no. 46 in D minor "A Fancy" (c. 1590) – The last of Byrd's keyboard fantasias; from My Ladye Nevells Booke (1591)

11. Prevent Us, O Lord (late 1560s/early 1570s) – Anglican motet written during Byrd's late Lincoln years or soon upon his return to London

12. Fantasia in 6 parts (mid-1580s) – Fantasia for viol consort from Psalmes, Songs, and Sonnets (1611)

13. Civitas sancti tui (1580/1) – From 1589 volume of Cantiones sacrae; second half of motet "Ne irascaris"

14. O Lord, Make Thy Servant Elizabeth Our Queen (late 1560s/early 1570s) – Byrd either wrote this piece when he was vying for an appointment to the Chapel Royal or soon after he got the post as a tribute to the Queen

15. The Eagle's Force (c. 1611) – Three-part song that opens Psalmes, Songs, and Sonnets (1611)

16. My Mistress Had a Little Dog (post 1596) – Consort song that describes a humerous incident at Appleton Hall, Norfolk