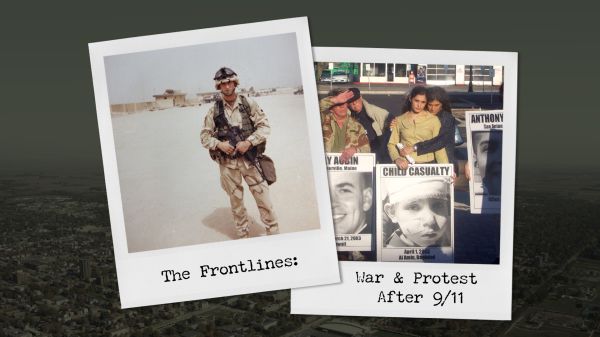

The Frontlines: War and Protest After 9/11

Aditi Adve, Narrator

A warning: this program contains graphic descriptions of the attacks of 9/11 and events following, and may not be appropriate for all listeners.

This September marks the 22nd anniversary of the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001. To understand how an event that happened over 800 miles from Champaign-Urbana continues to impact our community, the Uni High Oral History project collected perspectives from community members who lived in Champaign-Urbana, New York, and Washington, DC on 9/11/2001, members of the local Muslim community, veterans who fought in Iraq and Afghanistan, and university experts. Through the podcast series, “800 Miles from Ground Zero: 9/11's Impact on Central Illinois,” we hope to better understand how 9/11 both divided and brought a nation together. This is “The Frontlines: War and Protest After 9/11,” the second in our series. From 2003 to 2011, the United States spent almost 1 trillion dollars fighting an 8-year-long war in Iraq after invading the country. And until very recently, U.S. soldiers from across two generations had been fighting in Afghanistan for more than 20 years. In this episode, listeners will consider the U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq post-9/11 through the voices of veterans, anti-war activists, and academic experts.

From Uni High, I’m Aditi Adve, a member of the Class of 2023.

The attacks of September 11th, 2001, shocked the nation, leading to broad support for military action against the groups or nations responsible for the attacks. A Washington Post/ABC poll conducted two days after 9/11 found that 93% of Americans supported such military action. In October 2001, less than a month after 9/11, the United States launched Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan. In the months and years after September 11th, the United States went to war, first in Afghanistan, whose Taliban-led government allowed for Osama bin Laden’s Al Qaeda to operate within the country, and then in 2003, in Iraq, after the United States government declared a link between Iraqi dictator Sadaam Hussein and the 9/11 terrorists — a link that would later be proven false. The war in Iraq would last eight years, officially ending in 2011. And, on August 30, 2021, the last U.S. troops pulled out of Afghanistan, marking an end to almost twenty years of American soldiers serving in the country, a time frame spanning two generations.

Angela and Daniel Urban, who now live in Urbana, are both veterans of the War on Terror. They met in the U.S. army while stationed in Hawaii. Both Angela and Daniel joined the military right out of high school. Angela grew up in Alabama and Daniel in Pennsylvania.

Angela Urban

I wanted to see the world and I wanted to be able to experience other cultures. And so I just ended up going to the recruiter, kind of on a whim, and saying, “Hey, I'm interested in doing this. How do you do it?” I just decided. So I told my parents, I said, “I want to join the army.” And my parents actually were artists. They did not have the mindset of military at all. So they kind of just laughed it off. But when I actually brought the paperwork to them with the recruiter and said, “Please help, sign on the dotted line.” And they realized it was a little bit more serious, but still, they did not think I was actually gonna go.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Daniel’s family also didn’t have any expectations that he’d join the military.

Daniel Urban

But in my mind, it was the only way I could see a future where I might go to college. So you signed up and they had the GI Bill, which would pay for me to get my education at a later point in time. Other than that, I guess the perfectly honest answer is to get as far away from home as possible.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

When September 11th happened, both Urbans were stationed in Hawaii. At the time, Daniel was participating in an intense leadership development course at an isolated compound in the Hawaiian woods.

Daniel Urban

Everyone got put on alert. They pulled all of us out in formation in the pitch black, and basically told us that the United States was under attack. And it was most definitely a game-changing moment for anyone in the military at that time.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

While it was 3am in Hawaii when the planes hit the Twin Towers, unlike Daniel, Angela was awake, working a night shift as an intelligence analyst. She recalls the moment another officer shared the news of the attack.

Angela Urban

One of my coworkers was coming back from his lunch and he says, “Guys, you gotta stop and you gotta come, you gotta see this. A plane just hit one of the World Trade Towers.” And so we were like, is he joking? What's going on? It went from even the newscasters didn't know what was going on to, this is a terrorist attack. This is not April Fools. It's not a joke or some kind of weird stunt. This is real and we're under attack. So there was this very brief time of going from confusion- being stunned, confusion, and then reality sinking in.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

After 9/11, Angela was sent to Saudi Arabia to join a military intelligence operation. Daniel prepared to deploy to Afghanistan only to be reassigned to focus on the initial ground invasion of Iraq. Daniel describes some of the region-specific training he had in the military.

Daniel Urban

The language training, admittedly, was minimal because you're not going to learn Arabic in that short a period of time. I recall being given, like, a small pamphlet with some common phrases to help with a few things. But for the most part, as far as language is concerned, we were very reliant on interpreters, and there was a great shortage of Arab interpreters. So I remember the military having a recruitment push for anybody that was willing to sign up to take on that type of job. There was cultural training as well about Islam and the practices and Middle Eastern culture in general.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Daniel describes his first tour to the frontlines in Iraq with the 82nd Airborne.

Daniel Urban

One of the biggest things that stands out in my mind is our reception between my first and my second tour in Iraq, in that, I remember a lot of talk beforehand. Politicians saying, “we will be greeted as liberators!” And funny enough, a lot of people actually did greet you that way during that first tour. Saddam Hussein's regime was an incredibly repressive regime. We may not have gone in for the right reasons. Everything that was said was basically proven very quickly thereafter to not be true. But, as far as the oppression on a lot of the people, that was very much accurate. So there were actually a lot of people that were happy to see us that first-time around.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

President George W. Bush declared “Mission Accomplished” on May 1st, 2003 — six weeks after the U.S. invaded Iraq. At the time, nobody knew that the war would actually continue for eight more years. For the Urbans, Bush’s May announcement meant that they would be reunited — Angela would soon come home from Saudi Arabia, and Daniel would return from Iraq. This reunion would set in motion a new chapter in the Urbans’ lives as military spouses.

Daniel Urban

Historically, whenever there are troops deployed to a war zone and then they come home, there is a massive spike in births nine months after that. Fort Bragg was no different than that. I had a very quick turnaround. I was only back for two months. And there was quite a number of people that I know who were already prospective parents. What I distinctly recall is that most of those people were taken off of that second deployment roster and allowed to stay home with their partners and help with the pregnancy. I was specifically told that my role was too important, there was nobody that could replace me and I did not have that option. I had to be deployed. Everyone swore up and down that they would make sure I was back in time. I distinctly recall receiving the phone call. It was actually, a friend of mine happened to call back to talk to his wife one evening. And there was a whole network of a lot of the people that I work closely with, that the spouses were all a pretty tight-knit group as well. And her telling him, “Where is Urban? Find him. His wife is in labor right now!” I remember jumping on that phone call and by the time I got there, she had just had the baby. And he was premature. He's about six weeks premature at the time. So they took him and brought him directly to a neonatal intensive care unit. There were a lot of emotions that night. I remember walking out of that opp center and just going to sit by myself in one of the vehicles. So there is obviously the joy that you had a child born. But a supreme sense of just sorrow that I wasn't there for that. And I remember eventually my first-line supervisor came out to check on me and see how I was doing. And the first thing I said to him is, “I am not reenlisting.” I told him that night. I still had about a year and a half left on my enlistment at that point in time. “I'll definitely finish out my time. I will continue to be the superior soldier you have come to expect of me, but under no circumstances should you expect me to sign that dotted line again.” That was my breaking point.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Angela shares what it was like for her to give birth to their son, not knowing if Daniel would make it back from his tour.

Angela Urban

The whole time he was gone, I didn't know that I would ever see him again. And yeah, here I was, having his son, and I just immediately wanted to talk to him. And when someone is at war and deployed like that, you can't just pick up the phone. There weren't cell phones, just readily usable and stuff like that. So I couldn't even convey to him that all of this was happening. And on my side, everything was just moving so rapidly. And I just wanted to talk to him. And he ended up finally getting through to me after I had already had Demetrius, my son. And I was still in labor, just the after part, when I was finally able to talk with him. But I still didn't know if he would actually get home to see our child.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Angela was right to worry about Daniel. As he describes, this second tour was very different from the first.

Daniel Urban

What was amazing is how quickly that goodwill can be burned. And I came back in either August or September. And it was a complete 180. It was like entering a different country in how people felt about us at that time. Because I think the general idea is that, from the general populace of Iraq, is that we would come in, overthrow Saddam Hussein's regime, and then immediately leave and turn it over to them. And of course, as history shows, that is not what we did. So we had worn out our welcome very, very quickly and there was a lot more hostility in that second trip.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Daniel’s second tour in Iraq began late summer 2003. By this time, the Iraqi army had been disbanded by U.S. diplomat Paul Bremer acting in his new role as head of the Coalition Provisional Authority in Iraq, tasked with governing the country until elections could take place. During this time, an Iraqi insurgency organized against the coalition forces. Daniel explains the challenge of this insurgency.

Daniel Urban

The longer you stay somewhere, you start losing friends and gaining enemies very quickly. And some of that is just in the fact that you are there and some of that is in the way you treat people while you are there. And so that at some point, I don't remember if anyone declared an actual date of when we switched from fighting Iraq's army to fighting an insurgency, but that's what we were doing. It is a completely different type of war to go against the conventional army than it is to go against an insurgency. Being in people's home turf and their own towns, they know where everything is. They have the will of the people on their side. So, you think of a conventional war as being between people that are all in uniforms and on very distinct sides of a very distinct battlefield. And that is not what you had very shortly after we went in there. You have people that blend in with the rest of the population because that's what they are. They're part of that population. That's their town, they’re dressing the same way, they look the same way, only they may or may not be armed.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

During this second tour, Daniel worked out of a U.S. military base in Ramadi, Iraq. At this time, the base experienced near daily attacks, including an attack that killed someone in his unit.

Daniel Urban

One of those attacks was — here's one of those military acronyms for you again — a VBIED. A vehicle borne improvised explosive device. Which was basically a truck that somebody had rigged up and wrapped the engine block with a bunch of artillery rounds. And they put a switch in the car to trigger it. That vehicle got on our base and was triggered and exploded. There was a soldier who was standing right next to that vehicle at the time who was killed instantly. It actually exploded right in front of the building that everyone in my unit was using as a place to sleep. The building that I was working out of at the time was less than a 100 yards away from it. And for context of the size of this explosion, it blew out every window within about a mile or two radius. It was not a small explosion. So there were a number of people injured that day, some from shrapnel from the explosion, some from flying glass, some from facades of the buildings that crumbled from the impact of that. Yeah it was not a good day.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Fortunately, Daniel did make it back safely to the United States. However, as is true for many soldiers returning from war, the transition was not easy.

Angela Urban

It was incredibly emotional. Yeah. On the one hand, we're just so happy to have him with us. On the other hand, he was not the same when he came back. He had lived through an experience that was totally separate from what I was living through. And so even the garage door opening would send him down. And they call it PTSD, but that's just something that happens when you're in this kind of environment where bullets are coming at you. So it was very hard in those beginning times for him to even understand what it meant to be a father, because he was still trying to defend himself, in a sense, or trying to get himself out of that mindset, even though he was safe in our home.

Daniel Urban

It is a difficult transition. Not only there's a difficult transition in coming back from a combat zone, even when you're still in the military and getting back to your regular life in garrison back in the United States. For obvious reasons, some people are a little jumpy. When you get out, loud noises in a war zone are usually indicative of something very, very bad. I have a distinct memory of pulling into my garage one night shortly after returning, and before I entered the house, my wife had pressed the button to close the automatic garage door, which was a very loud unit. And I hadn't seen her go next to the button or press it and the noise caught me off guard and I literally dove underneath of our car because I was still so close to that mindset. There are two transitions in this. I mean, there's the difficulty of getting back into an environment from a deployment and accepting that you're in a safer space and you don't need to be hyper-vigilant all the time because that is something that definitely is hard to turn off. The other transition, just getting out of the military into civilian life, is something that faces its own set of hurdles.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

According to a Rand Corporation study, nearly 20% of veterans who served in the post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan and Iraq screened positive for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

War not only took a personal toll on the lives of soldiers, but it challenged many Americans to consider the purpose and ethics of war. While military action received broad support in the immediate days and weeks after 9/11, not everyone supported this mindset. Local anti-war activist Karen Medina, and others like her, started organizing as soon as 9/11 happened.

Karen Medina

I'm going to say that people in this community immediately, like that day, immediately gathered together and said, “the United States government and other people are going to use this as an excuse to invade other countries. We need to stand up and say this is not the right way to go.” I am the most proud that people in this very, you know, it's a small community, knew immediately what was going to happen and gathered together. And that was the first thing that they wanted to do was to not lash out, but rather to come together and to do something. And knew that their strength was in coming together.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

This strong desire to come together to amplify each other's voices was widespread throughout the Champaign-Urbana community. Stuart Levy had been regularly attending anti-war protests since 2002. He believed that engaging in war was never a necessary — or even a good — choice to make. His internal hunch that 9/11 would be used to justify major injustices, domestically and internationally, led him to become an active member of the local anti-war community.

Stuart Levy

I had the same feeling, like, this is going to get used as an excuse for repression at home and making war abroad. That was clear, like, within the first hours, even though we didn't really know what was happening, it was clear that it was going to be an excuse for that.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Both Medina and Levy were active in the local group AWARE which stands for The Anti-War, Anti-Racism Effort. They recall how they first got involved.

Stuart Levy

We were already well along in the war in Afghanistan and it looked like we were heading for a war in Iraq, a much bigger one. And I thought, “This is terrible.” So I just started going to the demonstrations that I heard about. I probably heard about them on WEFT, the local radio station.

Karen Medina

I found AWARE through my sister. You can either stay at home, on your couch watching television, or you can actually get out and do something. And if you can't stop things, at least you can say it should stop.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Levy and Medina weren’t the only people in Champaign-Urbana concerned about war.

Karen Medina

A hundred people came to the first meeting. The organizing meeting happened the day of 9/11. And then they decided that they were going to go ahead and start a group called AWARE. A hundred people came to that first meeting, and then it spread. So, like, if you have your first meeting there's a hundred people at it, it means that people feel like something needs to happen. And so what some of the people, looking back on those emails, what a couple of the people were doing were just talking to other people around them and saying, “What do you think about what's going on or what's going to happen?” And, the vast majority of people's responses that they got were, “This is really scary. We’re against the U.S. going to war. But we don't know what to do about it.”

Aditi Adve, Narrator

The first AWARE meetings had strong community engagement drawing a diverse group of people concerned that the United States government would take advantage of people’s fears in negative ways. This engagement motivated the group to provide education to the community about the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as protest the wars in highly visible actions, as described by Al Kagan, a retired librarian at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and AWARE member.

Al Kagan

I think the most obvious thing for many people in the community is that we used protest every Saturday morning. No matter what the weather, what season of the year it was, in the snow, we were over on Prospect Avenue near the freeway on-ramp and off ramp. We had maybe a couple hundred people there almost every Saturday morning. So we did that, we had speakers, we had programs, we invited, for instance, antiwar veterans to speak. We had “boots on the ground,” it was called. It was a number of pairs of boots in a field that represented all the people that had died from the Iraq war. And we did things like that.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Medina describes some of AWARE’s protests that took place on the campus of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Karen Medina

People here in the United States were just going shopping. It wasn't really affecting them unless they had someone in the military. And so we had die-ins on campus in the middle of the street. When there's, like, an all-walk time, when the cars are all supposed to stop and then you can walk in any direction at certain corners. So we would have people go to the middle of the street, lie down in the street, and then, at the right time, they would stand up and get off. Just to remind people that people were dying. Because the United States had invaded other countries and was at war. We shouldn't just be going about our daily lives as long as war was happening

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Levy shares a memory of another direct action.

Stuart Levy

One project was called Postcards for Peace. We organized as many people as we could to write just postcards to our U.S. rep and to our senators asking them various things, but basically asking them to bring the troops home and end the wars. And they got something like a thousand-odd postcards. I was looking this afternoon and found pictures. They've got huge blocks of postcards that they just, sort of, handed to the post office and said, “Here.Send these.” So that was a thing. Another organized thing was, I think along with some people from the National Association for Mental Illness, or NAMI, they were talking about PTSD. This might have been 2007, 2008. There were several local people who were anti-war veterans and were very active in Iraq Veterans Against the War. Iraq Veterans Against the War kind of followed in the footsteps of the Vietnam Vets Against the War. So they did a local event called Winter Soldier, which was something that had been done in Vietnam time under that sort of name, where people just kind of talked about their experiences, and talked about the indoctrination that had led them to say that it was a legitimate thing to go and kill people on the far side of the Earth. A local medic talked about what it was like to be a medic in a war zone, treating a very seriously wounded person.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Some of AWARE’s efforts were more social and creative which provided opportunities for people in the anti-war community to connect informally about a common concern.

Karen Medina

It can be anything from, like, having a film and a speaker, or a teach-in, or they had potlucks. They had sign-making, they had art-making, zine-making. They joined with other groups. They did songs. There was the Ladies Against War, and then the Ladies and Laddies Against War. They were just updating each other on the news. Like, we had one person who was really good at reading news from a bunch of different sources and then summarizing them.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Other AWARE events provided a crucial space for difficult conversations and dialogue about this challenging moment in history.

Kare Medina

There were a lot of people that felt like there was nothing that they could do. So I think starting the conversation was really important. And I think entering into conversation by having a table, or by having a television program, or by having a movie that people can come to, or by having a speaker. Those discussions. And sometimes the discussions start off as, “How dare you be out here? My son is in the military. How dare you be against the military!” And then we would say, “We're not against the military. We’re against the U.S. using the military to accomplish — the only word I can think of is idiotic — goals, or to accomplish things that we should not be losing the life of your son or daughter. Sacrificing. That shouldn't be happening.” And so by just engaging in that, then all of a sudden, the parent that was just a second ago yelling at us realizes that they really also have these thoughts too. And so, I think it's really important not to stay in your own silo and think you have all the answers, but actually to meet the people that might slightly agree with you or might completely disagree with you. And having those conversations is essential for changing anything.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Kagan, who had lived through the Vietnam War era, saw connections between that war and these post 9/11 wars.

Al Kagan

It was shades of the Vietnam War, when the U.S. attacked Afghanistan and then Iraq and now bombing other countries going on as well. It was so traumatic to have the war in Vietnam. And then to see what commentators called a “Vietnam Syndrome,” which meant that people didn't want to go to war anymore. And then finding out that after a certain time the new generations were growing up and that other generations could be influenced to support wars again. As they say, before 9/11, there was a period when the U.S. was not engaged in very much war. And now they are again. And I think it affects everything in society. If you're focused on war, you're not focused on something else. You're not focused on better quality of life for people.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

The last U.S. troops left Iraq on December 18, 2011, and Afghanistan on August 30, 2021. Looking back on the wars, interviewees shared different perspectives. Here is University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign political scientist Nicholas Grossman.

Nicholas Grossman

The original invasion of Afghanistan was necessary and was the right decision. The invasion of Iraq was unnecessary and the wrong decision. In part because it distracted the United States from the project in Afghanistan, which now that we know has ended in failure — though it took another 17 years before it did — but was a distraction from that, and also drove a lot of sympathy to Al Qaeda, or at least to anti-American forces around the world. Things like the Abu Ghraib torture scandal, where U.S. operatives tortured pretty grotesquely a bunch of Iraqi detainees. And photographs and evidence of that going around the world are not only immoral, but also the photographs of the images of them are a more dangerous anti-American weapon than some bombs.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Jeff Brown, the current Dean of the Gies College of Business, who worked at the White House on 9/11/2001 reflects on his complicated feelings about the war in Iraq, including recalling an experience of many American citizens: initially believing the intelligence shared by President Bush’s Secretary of State Colin Powell at the United Nations in February 2003 that purportedly linked Iraq to 9/11.

Jeff Brown

I had huge confidence in Colin Powell, who I just — to this day — viewed as one of the greatest public servants we ever had. And when Colin Powell stood in front of the United Nations and made the case for why Iraq was a threat, I believed him, and therefore I was supportive of the war. Now, subsequent to that, we learned that a lot of that intelligence was wrong. Some of it may have been fabricated. So, knowing what I know now, I think it was a mistake. But with the information I had at the time, I was supportive.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

War veteran Daniel Urban’s answer when asked if the United States should have gone to war with Iraq.

Daniel Urban

I'm gonna say no. Not unless they had given us a more legitimate reason. And a second caveat onto that is, not unless they had a very clear and definite exit strategy. All of the things that were laid out for why we were there, any unseen, elusive, tenuous connection to 9/11 was clearly fictitious. Weapons of mass destruction, also another fiction there. I think the worst of it for me is being sent into that situation under these false pretenses. Is it a bad thing that Saddam Hussein was overthrown? No. If there's one good thing to come out of it, it was that. Even after that, we continued to stay there for well over a decade, as far as I'm concerned, making the situation worse the longer that we were there.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Fauzia Rahman had been a Muslim student at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign on September 11, 2001, and remains active in the local mosque today. She brings another perspective of war, which includes considering the impact on civilians living in countries impacted by the War on Terror.

Fauzia Rahman

I could not support the war in Afghanistan ever. The war in Afghanistan- and now my sister currently is working with refugees.There has been a new influx of Afghan refugees as America has pulled out, and there are more displaced persons. You know, I just never bought into this war. For me, that war itself, and what it has done to the Afghan people and continues to do to this day, the story hasn’t gotten any better. It's the drone strikes, and just families being displaced. A lot of them going into Pakistan, and other places. They don't have a home. It's very difficult being in that life circumstance, not having a home. And then having to adjust to a new place. Amidst Islamophobia. I think it's that war on terror that continues to go forth, and to every president, even Obama, he didn’t stand up. He started the drones. I mean, that's huge. That’s huge, for not just the people in Pakistan and Afghanistan, but Yemen, everywhere where it's being used, drone technology. It's upsetting to just read about it, what it does to people psychologically. To little kids, when you hear that noise overhead.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Grossman offers the following observation about why the United States struggled with the war in Afghanistan — America’s longest war.

Nicholas Grossman

Another problem was that the United States never totally defeated the Taliban insurgency, the former government. And ultimately, with insurgent warfare, as the Soviets learned when they invaded Afghanistan in the 1980s, or as the United States learned when they invaded Vietnam, that the people who are fighting for their freedom have a advantage over foreign invaders, in that the United States could leave Vietnam or leave Afghanistan and still be the United States. Whereas for the Taliban and their supporters, if they quit, then Afghanistan would not be Afghanistan anymore. It would be like some America Junior, to them, abomination. So they think they're fighting for their very freedom, their very independence. And in Afghanistan in particular, a lot of them had fought a lot before. Where they could point to things like, “My father fought the Soviets, and my great grandfather fought the British, and they outlasted them, and we’ll outlast the Americans too.” And, they did.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Brown University’s Cost of War Project estimates that these post-9/11 wars have cost the United States $8 trillion and have killed more than 900,000 people, a figure that includes members of the U.S. military and allied fighters, opposition fighters, civilians, journalists, and humanitarian aid workers killed as a direct result of war. Here, in Champaign-Urbana, people live among us who studied these wars, fought in these wars, protested these wars, have been displaced because of these wars, and have loved ones currently living in the war zone as the region remains volatile today. Jeff Brown, who worked at the White House on 9/11 and remembers the smoke rising from the Pentagon after it had been attacked, leaves us some parting words on remembering 9/11 in history.

Jeff Brown

9/11 really was a pivotal moment in U.S. history, and the implications of that day are still with us. It has affected every presidential election since that day. It has affected how we are perceived on the global stage. Almost any issue that has to do with foreign affairs, with security, even with the economy, has a history that traces back — in part — to that day And I think it's really important for people to understand that, and for the younger generation — that, in many cases, was not even alive on that day — to understand this really wasn't very long ago. And we're still living with the implications of that day.

Aditi Adve, Narrator

Thank you for listening to “The Frontlines: War and Protest After 9/11,” the second episode of “800 Miles from Ground Zero: 9/11's Impact on Central Illinois,” a student-produced podcast by Uni High’s oral history project team. Each episode in this series focuses on an aspect of American life post-9/11, including memories from the days and weeks following the attacks, military and anti-war efforts, changes to domestic policy, and rising Islamophobia. All interviews featured in this podcast were conducted in Spring 2022 by Uni’s eighth-grade class. Please tune in next week to hear about how domestic policy post-9/11 changed everyday life, from travel to the handling of library records. If you’d like to listen to previous episodes of “800 Miles from Ground Zero: 9/11's Impact on Central Illinois,” check out the WILL website at will.illinois.edu/illinoisyouthmedia.

The events of 9/11 led to America intervening in the Middle East through the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Despite having strong support when they first started, the wars resulted in intense controversies throughout the United States. This this second episode, The Frontlines: War and Protest After 9/11, we hear from multiple veterans, anti-war activists, and experts to understand the different perspectives on the post-9/11 wars.

FEATURING

Angela Urban was an intelligence analyst in the military during 9/11. She describes watching the plane hit the towers on TV while on shift, and realizing a terrorist attack was underway, as well as what it was like to have a husband deployed to Iraq while pregnant with their first child.

Daniel Urban was active military in Iraq. In this episode, he explains the mindset that veterans had during after the wars, and how coming back into society was a difficult transition.

Karen Medina, Stuart Levy, and Al Kagan were anti-war activists that actively engaged in some of the local protests against the wars. They talk about how the community came together in response to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Nicholas Grossman is a professor of political science, and an expert on terrorism. He describes the unprecedented sense of patriotism in the nation following 9/11.

Jeff Brown worked in the White House on 9/11. He provides his unique perspective as a government employee and explains why he supported important political figures such as Colin Powell during the wars.

Fauzia Rahman tells a powerful story about the destruction in Afghanistan to argue how the wars were completely unjustified.