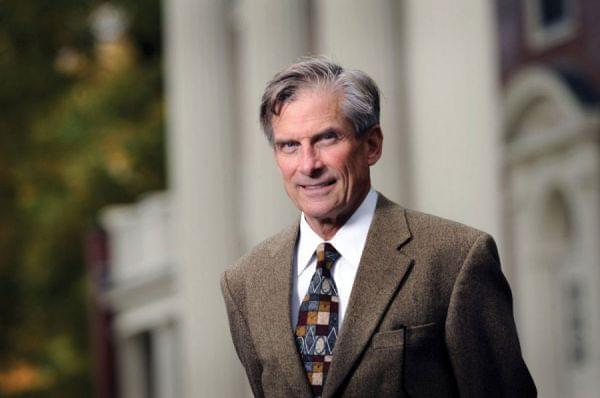

NEH Chairman William Adams On The Humanities’ Role In The US

William "Bro" Adams Fred Field/Colby College

The Chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, William Adams, does not go by his given name. He goes by Bro. It was a name given to him by his father that stuck.

"When my father came back from [service in World War II] he began to call me Bro at a very young age in memory of his dear friend." said Adams. "When I became tempted to change the name as I got older and it became odd in some ways my mother reminded me that it was my father's name for me. My father died when I was seventeen. So, I've kept it."

I think the humanities reveal how we’re part of stories bigger than ourselves and one sphere of that story is certainly the human story. William "Bro" Adams

Adams, too, served in the military. He enlisted and spent a year fighting in Vietnam with the army. "It was a big part of my life. A big part of my interest in the humanities came from that. After I got back from the Army and re-enrolled at Colorado College I had the great good fortune to come into the company of a number of philosophers," said Adams. "They helped me understand through their work a lot of what I had been through."

From his studies at Colorado College, Adams was inspired to go on and pursue a graduate degree though an interdisciplinary program in the humanities called the history of consciousness program at the University of California at Santa Cruz and "that kind of sealed the deal in terms of my own commitments and I went off and started a career in the academic world, which went on to become an administrative career but it certainly started with the humanities and how fundamentally important they are to the lives we live as individual people, but also to the lives we lead in community with other people."

President Lyndon Johnson signing the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act that created NEH and NEA in 1965.

Before becoming the Chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, Adams served as president of Colby College and Bucknell University and coordinated Great Works in Western Culture program at Stanford.

Though, Adams says, it is easy to define the humanities in the way they are organized in academia, he prefers to define them by talking about “what the humanities are, in one way or another always concerned about. And that has to do, principally with our history, with our culture, with our ideas and our values.

Adams says that the humanities “are helpful in our everyday lives as individuals and with other people in all the complex and demanding forms of interaction and engagement with other people. … But they are also about … history of communities, history of nations, and history of the world in some sense. … and in some ways we’re connected with the whole long history of human beings and that history becomes bigger and bigger all the time.”

The Common Good Initiative Logo

Last year, the NEH launched an initiative called “The Common Good.” Adams says that the initiative is designed to promote the importance of the humanities and encourage increased scholarship, work, and discussion of some of the big challenges the country is facing.

Those challenges include, he says, our relationship with the natural world, the big new questions from the advances in science and technology, questions of citizenship and how we become productive citizens, the balance between liberty and security, and more.

Adams says that he has seen the term “Common Good” become “fugitive” in public discourse. “And, there are a lot of reasons for that. There are a lot of challenges to citizenship, currently. This is a big, complicated country. The political spaces in which we all operate are becoming larger and larger and more and more complex,” said Adams. “And it becomes harder and harder for us to get out of our sectional or personal interests in order to address these larger questions."

There’s not much more important than the preservation of a vibrant, energetic, democratic, political culture in the United States. William "Bro" Adams

He said that he hopes the NEH’s Common Good Initiative helps us as a country address some of these questions and is seeing conversations currently around the anniversary of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments, “about the relevance of that extended historical moment after the civil war to the current situation in which we find ourselves in this country now with respect to race.”

“As we encourage these public questions of humanities thinking we also know that we have to continue to support the fundamental humanities infrastructure in the country. Research and also preservation of cultural material that is required for that scholarship and also is valuable in and of itself as part of our public cultural and historical heritage,” said Adams.

Adams says the NEH was Ken Burns' first funder.

Adams says that over the last 50 years, the NEH has invested $5.3 billion in the cultural economy and sector and the National Endowment for the Arts has invested about the same. “And to presume that the private sector would have done that, is a fantasy. It just would not happen.”

“The combined budgets of the NEA and NEH are,” Adams says, “a tiny fraction in the many billions of dollars federal budget. And enormously efficient in terms of the impact that those dollars produce.”

“I’ll give you a good example from NEH’s portfolio: Ken Burns. We were his first funder with his very interesting film on the Brooklyn Bridge many years ago,” said Adams. They have continued to work with Burns and fund other documentaries distributed by PBS.

During his tenure at the National Endowment of the Humanities, Adams says he has two goals. The first is to demonstrate the public relevance of the humanities to the wellbeing of the country and the second is “to raise and hopefully stimulate thinking around the country – this question of the future of liberal learning and the future of our fundamental educational commitments,” said Adams.

“Those are the two most fundamental priorities on my mind. If I can make a dent in either of those I’ll be enormously pleased.”

Adams was on the University of Illinois campus on October 30th to, among other things, deliver a speech entitled, “The Common Good and NEH at 50,” that evening at the Spurlock Museum. While on campus he stopped by WILL for this interview. Adams’ visit is co-sponsored by the Illinois Program for Research in the Humanities, the U. of I. Office of the Provost and Spurlock Museum.