As African Swine Fever Marches Across Asia, U.S. Pork Industry Prepares

Farmers, state and federal agriculture department officials, law enforcement and others convened at Iowa's State Emergency Operations Center as part of a national simulation exercise practicing what to do if a deadly foreign animal disease arrives here. Amy Mayer/Harvest Public Media

The State Emergency Operations Center in Johnston, Iowa, has sloped auditorium-style seating and plenty of outlets to keep laptops and cell phones charged. This is where officials gather during and immediately after tornadoes and massive flooding.

It’s the center for crisis control.

That’s why in September, this space at the Iowa National Guard headquarters became the incident command center for a four day simulation exercise to test how well prepared Iowa and the other top pork-producing states are for an African swine fever outbreak.

The threat to the pork industry feels imminent – especially in this state, which raises more pigs than any other.

Iowa Secretary of Agriculture Mike Naig announces new information from the federal government during an emergency response simulation exercise.

“If we’re a leader in production, we ought to be a leader in how we respond,” said Iowa Secretary of Agriculture Mike Naig, who on the second day of the simulation took a break from the role-playing to talk to reporters. He said the simulation – which involved 14 states – poked some holes in plans his department had drawn up, which is exactly the point.

If a state identifies the African swine fever virus, it must send samples to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Foreign Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory, which is on Plum Island, off New York State. One of the challenges the simulation exercise threw at state officials was figuring out the fastest secure way to get a sample from the Midwest to that lab. A lesson learned? Charter flights are really expensive and it’s not yet clear who would pay for one.

Once the disease is confirmed in the country, the likely next step is a stop movement order preventing pigs, manure and even swine feed from crossing state lines. Individual states would have to decide how to set up and enforce such orders within their borders.

Amanda Luitjens, animal welfare auditor for Christensen Farms, came from Minnesota to participate in the exercise. She said her company, which has a network of hundreds of farms in Minnesota, Nebraska, Illinois and Iowa, tracks every person, pig and vehicle that comes and goes. If the company had to determine if a specific animal or a certain truck that’s associated with an infected site had been through one of their farms, they could.

“We are spending a lot of time and energy working on these plans that all of us hope we never have to use,” Luitjens said.

Perhaps what’s most vexing is that there’s no way to know whether the preparations they’re making will ultimately prove useful if the virus gets here. But Luitjens said even if what they need to do in the moment is different than what they’ve prepared for, the fact of writing and testing plans will help them respond appropriately.

“We also understand this is a new and evolving beast,” she said, “so it’s going to be changing.”

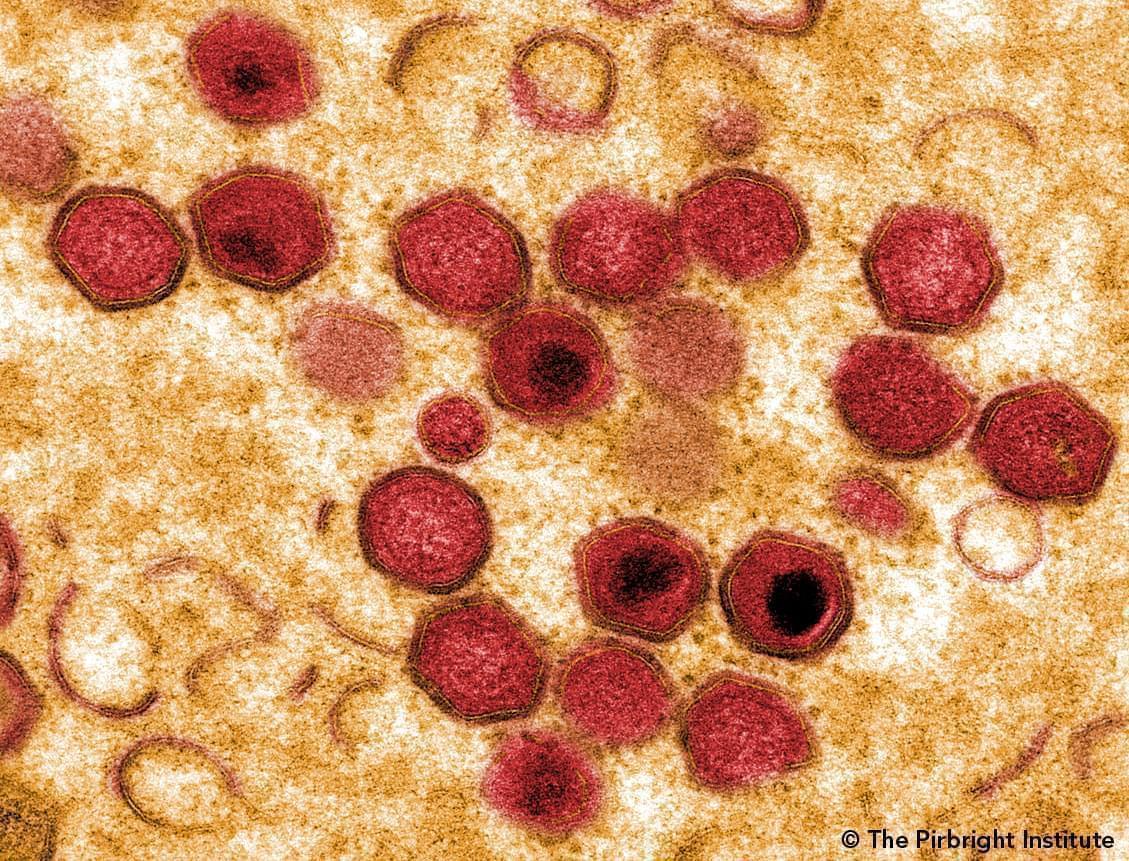

African swine fever virus as seen through a microscope.

Virus is spreading

Currently, African swine fever is nowhere in the western hemisphere, but it could arrive on any plane or ship from an infected country.

“It won't come across our land borders unless it first gets into a different country,” said Iowa State University veterinary medicine professor Jim Roth. “So the major concern is people and products from positive countries, and there are more and more positive countries all the time.”

The African swine fever virus first infected hogs in China in August 2018 and since then, it’s devastated that country’s pig population, which is the world’s biggest. The rapid spread within China and from there to neighboring countries is part of what prompted the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the 14 participating states to want to test their readiness.

Roth participated in the simulation from USDA’s incident headquarters in Maryland. He’s been involved with creating the Secure Pork Supply Plan, which outlines how pork production would resume after the stop movement order following confirmation of the disease.

While the U.S. was running its hypotheticals, Roth said, infections spreading across Asia provided a sobering reality check. From China, the virus moved into North Korea, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar and the Philippines.

“We've learned a lot from what they've done in those other countries. But what we've learned is, they haven't been able to stop it,” Roth said. “So we need to really be prepared.”

As the simulation continued in the United States, South Korea announced its first cases, its first stop-movement order and a massive disinfecting effort.

South Korea’s pig farms, in general, had biosecurity measures and other defenses in place, leaving it looking about as prepared as the United States, said Kyoung-Jin Yoon, a veterinary pathologist at Iowa State University who watched from Ames as South Korea responded.

Yoon said farmers everywhere expect to see sick pigs at times, so they’re not immediately alarmed by a pig who has a fever or stops eating. They may try to treat such an animal themselves. With the threat of African swine fever, South Korean producers were coached to monitor for specific symptoms that Yoon said didn’t always show up.

“Immediately, people recognized that the clinical signs that the textbook describes (are) not always there,” he said.

Two pigs meet in a barn during the 2018 World Pork Expo in Des Moines. The 2019 event was canceled because of fears the African swine fever virus would come along with visitors from infected countries.

Quick reaction

So now, and for U.S. producers, Roth said, “(the) message is, call a veterinarian right away.” Don’t wait for additional symptoms.

Roth and Yoon agreed that should hogs in the United States become infected with African swine fever, pork dumplings and bacon could become scarce globally.

“The world is going to have to reckon with a shortage of pork, and how do we do that?” Roth said.

On the other hand, planners recognize that if the disease is confirmed in the United States, export markets would likely shut out U.S. pork, while at the same time consumers here might lose interest in the meat. That would cause the opposite problem: a glut of cheap ham and sausage in the United States.

The virus doesn’t threaten people and all sick pigs should be diverted from the food supply.

For now, precautions remain strong. Some swine shows and events have been modified or canceled. Oklahoma recently became the 23rd state to ban garbage feeding, which is a regulated system of giving pigs cooked food waste. And the USDA has brigades of beagles sniffing for contraband salami at airports.

As with other types of emergency planning, there’s no way to know whether it’s enough unless the crisis happens. And nobody wants to put those types of plans to the ultimate test.

Follow Amy on Twitter: @AgAmyinAmes