Culture Shock: Teachers Call Noble Charters ‘Dehumanizing’

Ann Baltzer (far left) posed for a yearbook picture with her advisory students at Noble's Hansberry College Prep. The dress code didn't require certain sock colors, so Baltzer says students chose bright colors to express themselves. As a teacher, she had earned the right to wear blue jeans for one day because she had perfect attendance for the quarter. Courtesy of Ann Baltzer

The trend toward school choice has educators across the country looking at Chicago’s Noble Charter Schools — an award-winning network of mostly high schools that specializes in helping inner-city kids achieve the kind of SAT scores that propel them into four-year universities. But despite its prestigious reputation, Noble has a peculiarly high teacher turnover rate. And some of those teachers are speaking up about policies they describe as “dehumanizing.”

Noble’s handbook lists more than 20 behaviors that can elicit demerits. The dress code, for example, requires students to wear light khakis, plain black leather belts, black leather dress shoes, and school-branded polo-style shirts that must be tucked in. Hair must be only a “natural” color, and students can't have any designs in their hair.

Kerease Epps, who taught at Noble’s Hansberry College Prep, made sure to arrive by seven o’clock every day to help students with curved lines in their hair avoid punishment.

“Every morning, I would color in two of my boys’ parts,” she says. ”I had a hefty amount of eyeliner at my desk, so I’d just color in with black or brown eyeliner.”

Ann Baltzer taught chemistry at Hansberry. When one of her female students showed up with braids that included strands of maroon — the school color — the girl was told she couldn’t attend class. So she asked Baltzer to use a black marker to obliterate the maroon in each braid. The teacher looks back on that as not only unnecessary, but racist.

“To have a system that results in a white woman having to color on a black woman’s hair, and if I don’t, she’s excluded from education, there’s something wrong with that,” Baltzer says.

But some teachers embrace Noble’s policies. Annie Bell was fresh out of college when she became the chemistry teacher at Noble’s Johnson College Prep.

”If one of my students came to school with red hair, I would say, ‘You knew. You totally knew that you shouldn’t have red hair,’” she says.

With no prior teaching experience, Bell didn’t question Noble’s policies.

“I really trusted the system and I really trusted my principal,” she says. “And so I just enforced it all.”

Bell, however, believes the rules are necessary to mold low-income students into college material.

“I will say it’s easy to question one piece, but when I look at the system as a whole, I really think it needs all the pieces to accomplish what we accomplished,” she says.

Bell and Baltzer both left Noble after four years. That’s not unusual. Five Noble campuses lost at least half of their teachers over the past four years. Part of that is due to burnout: The charter network requires teachers to work longer hours, and often on weekends.

But some, like Baltzer, cite Noble’s “culture” as the main reason they left.

The network uses the word “culture” as a synonym for discipline. For example, each campus has staff members tasked with enforcing rules in common spaces (hallways, the lunch room, etc.). On some campuses, they’re called “disciplinarians,” but network administrators call them “culture teams.” Noble has two full-time auditors who drop in to observe classrooms on every campus to ensure teachers are upholding the culture. Baltzer and other teachers say they received professional demerits (sometimes called “mulligans” or YBTTs, short for “you’re better than this”) if an auditor found they weren’t issuing demerits for each infraction of Noble’s rules.

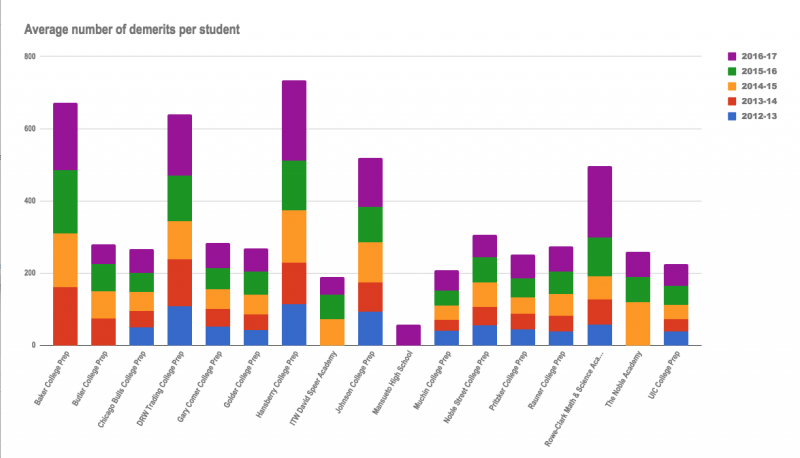

For students, demerits can be costly. Any four demerits (such as failure to wear a black belt) within a two-week period triggers an automatic 2-3 hour detention. Students who rack up 13 or more detentions during a school year have to attend “character development” class at a cost, until this year, of $140. Students who get 26 detentions have to attend two character development classes. Students who receive more than 36 detentions in a year are automatically ineligible for promotion to the next grade. Consequently, a significant percentage of students opt to transfer out of Noble rather than repeat a grade. Data obtained from Noble Network through the Freedom of Information Act shows that, over the past five years, the general arc bends up, toward increasing numbers of demerits.

Last year, the average number of demerits per student at Hansberry College Prep was more than 222, the highest of any Noble campus.

“It’s a completely dehumanizing system, both for teachers and students,” Baltzer says.

One of the policies that made her most uncomfortable was demanding “level zero,” or complete silence, in the hallways during passing period, which she says teachers could activate by yelling “hands up.”

“Teachers were applauded if you had the ability to shut down the hallway,” Baltzer says. “We had no awareness that it would be inappropriate to shout ‘hands up’ at a hallway full of black children. And so we had white teachers shouting ‘Hands up’ and kids putting their hands up and going silent. That is insane.”

Deshawn Armstrong, who graduated from Hansberry in 2017, says level zero sometimes extended from passing period to the lunch period.

“I do remember there was a period, my sophomore year, I want to say, when we were on level zero lunch and level zero hallways for approximately a month and a half,” he says. “So in essence, during the school day, there was no conversation taking place between students in the halls or at lunch, which is really the only time that we have the opportunity to speak to one another.”

Deshawn Armstrong at Brown University Black Appreciation Dinner

Armstrong excelled academically at Hansberry. He scored a 35 on his ACT, and is now at Brown University, having turned down admission to Harvard because it felt “too snobby.” But he has discouraged friends and relatives from attending Hansberry. Several times, beginning on his first day at Hansberry, students were physically searched by staff for unknown reasons, Armstrong says. “It felt like a prison.”

Ellen Metz, principal of Noble’s flagship campus, Noble Street College Prep, says the network’s guiding concept is that rules are grounded in purpose, rather than power.

“Some of the stuff that you’re talking about like the level zero for days and weeks, like, you know, we serve 12,000 families in Chicago. This would be headlines if this were happening on a regular basis,” she says. “Families would be up in arms, all 12,000 of them. And they’re just not.”

Myisha Shields is happy with Noble. She even traveled to the state capitol with Noble’s lobbyist to tell lawmakers how much her daughter Astazia enjoys being a sophomore at Noble’s newest campus, Mansueto College Prep.

“She says, ‘Mom, it’s a whole other environment! We can’t get away with the little things. The little things matter! Like when you sit with your head on your hand, you get a demerit,’” Shields says. “And I was like ‘Ok that’s good! It’s just teaching you how to sit up and stop being slouchy.’”

Astazia has a disability that qualifies her for an Individualized Education Program, or IEP, that includes a social worker on her support team at school. Shields says Astazia has never received a demerit, and is on the honor roll.

“She’s being challenged more at this school,” Shields says.

Ellen Metz is principal of Noble Street College Prep, the school that launched the Noble Network of Charter Schools.

Jane Sundius, a social psychologist who focuses on poverty, children and education, says low-income families tend not to question systems like those at Noble. She points to a study by sociologist Melvin Kohn, exploring how parenting styles vary by social class.

“What he found was that working-class parents focus very much on obedience. Off little Johnny went to school and his mom said, ‘Listen to the teacher! Be good! Be quiet!’ And upper-class parents focused on learning and creativity and having fun,” she says. “The working-class parents trained their children to be workers on an assembly line, not empowered, while the upper-class families taught their children to believe that they had a legitimate right to their opinion and their views.”

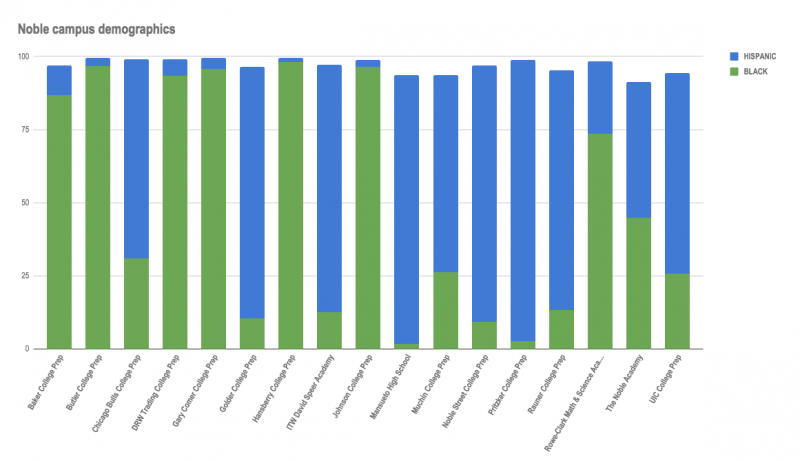

Discipline varies widely among Noble’s 17 schools, but data provided by the network shows students at five predominantly black Noble campuses (Hansberry, Johnson, Rowe-Clark Math & Science Academy, Baker College Prep and DRW Trading College Prep) last year got about twice the number of demerits as students at Noble’s 10 predominantly Hispanic schools. Two additional predominantly-Black campuses had lower demerit numbers, but they are different by design. One of them, Gary Comer College Prep, is housed in a newly-constructed building where every classroom has glass walls, to promote “transparency and accountability.” The other, Butler College Prep, is Noble’s “social justice” school, and most teachers and staff members are Black.

A look at campus demographics of Noble Charter Schools.

Like many other charter networks, Noble hires many teachers through Teach For America. It’s a somewhat controversial Peace Corps-like organization that takes high-achieving university students, gives them an intensive, five-week course in education, and then dispatches them to teach in inner-city schools. Some turn this character-building experience into an eye-catching item on their resume as they transition into a wholly different career. However, whether they plan to stay in the field of education or not, TFA teachers tend to be young and inexperienced, but committed and compassionate toward their students.

These attributes may contribute to Noble’s 40 percent turnover rate at the four-year mark. At Noble, each new teacher is assigned a 9th grade “advisory” — basically a homeroom of students they’ll see daily until graduation. They give these students their cell phone numbers, and answer calls or texts at all hours of the day and night. They become surrogate family members, and some get dubbed “Auntie” or “Uncle” by the students. Several teachers told me the reason they stayed at Noble was because they couldn’t imagine abandoning their advisees.

Kerease Epps is still in touch with her advisees, but these days, mainly by phone. She came to Noble after teaching in Detroit schools, and never made peace with Noble’s discipline system. Like roughly one in five Noble teachers at Hansberry, and many Noble schools, she left after just one year. For her, it wasn't just the hairstyle code (in 2016, Noble actually relaxed the one-straight-line rule, even though it's still in the dress code for teachers); it was the bigger stuff. She saw the first red flag during Noble’s summer training session for new teachers.

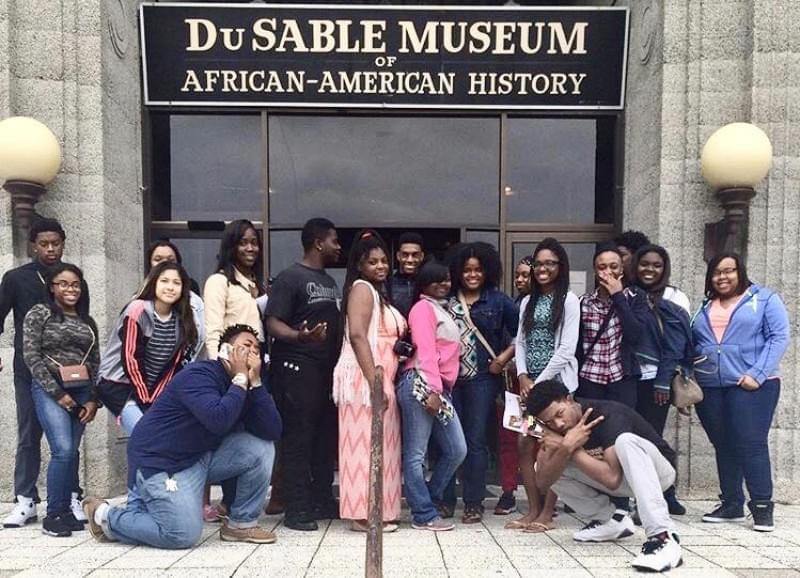

Kerease Epps (wearing glasses, a blue dress and gray sweater) took her African American History students on weekend field trips to museums. She left Noble after only one year, saying she felt "disaligned."

“They were going over the demerit system, and they said, ‘Light the students up.’ This was also the summer following the Sandra Bland incident,” Epps says. “The phrase the police officer used was ‘I’m going to light you up.’ So the fact that there was no sensitivity around how we’re using that phrase in regards to discipline broke my heart the second week of new-teacher training.”

She relished getting to teach African-American History using a rigorous curriculum she designed herself, and spending weekends taking her students on field trips that got them special access to museums. But by the end of one year, she says, she felt so “disaligned” with Noble that she realized she had to leave.

“That moment came when I sat and reflected on the fact that I trained my students to close the door if a student was being perp-walked out of our building, which happened often,” she says. “Because for discipline issues, like a fight, our children were arrested and walked out of the school. And I was useless. I could not help that child.”

Epps now works as a public policy fellow for the Illinois State Board of Education. Baltzer is taking a year off teaching, but hopes to find a job with Chicago Public Schools. Bell is busy raising her two young children and taking graduate school classes to be a school counselor.

Noble officials privately suggest that Baltzer and other former teachers are speaking out about discipline purely because charter school teachers are trying to unionize. And it’s true that Baltzer fully supports unionization efforts. She contributed an essay to “Why I Left Noble” — a blog founded by former Noble teacher Amethyst Phillips. The blog’s cover photo is a union logo. But Baltzer points out that she has nothing to gain from unionization efforts, having already resigned from Noble.

“The reason I'm speaking out is simple: I cannot sit by silently as students I love and care about are treated this way by the public educational system,” she says.

She recently applied for a job in another urban school district, and was alarmed that its administrators aspire to emulate Noble.

“That was terrifying to me, that Noble is being used as a model for urban education not just in Chicago but across the country,” Baltzer says, “because only one side of the story has been told — that of the networks.”

In Illinois, Noble Network gets support from across the political spectrum. Both Gov. Bruce Rauner and the family of his Democratic rival, J.B. Pritzker, have donated enough money to Noble that they have schools named after them.

Illinois Newsroom is a regional journalism collaborative (RJC) focused on expanding coverage of education, state politics, health, and the environment. The collaborative includes Illinois Public Media in Urbana, NPR Illinois in Springfield, WSIU in Carbondale, WVIK in the Quad Cities, Tri States Public Radio in Macomb, and Harvest Public Media. Funding comes from the stations and a grant from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB).