Illinois Issues: Charlie Wheeler On The Past And Future Of Statehouse News

Charlie Wheeler began covering Illinois government five decades ago at the 1970 Constitutional Convention. Clay Stalter/UIS Campus Relations

Charlie Wheeler has been covering Illinois government for 50 years. As he retires from leading the Public Affairs Reporting program at the University of Illinois Springfield, he reflects on the decline of the Statehouse press corps, the threat that poses to democracy, and the rays of hope in non-profit news.

Few people have been following Illinois state government as long as Charlie Wheeler.

From 24 years at the Chicago Sun-Times to another 26 heading the Public Affairs Reporting Program at the University of Illinois Springfield, Charlie has seen the heyday and gradual decline of Statehouse news coverage.

This week's Illinois Issues in-depth report includes excerpts from a speech Charlie gave on the subject earlier this year. He also sat down to talk about the future of state government news with Statehouse reporter Brian Mackey.

In 1969, Charlie Wheeler was just back from three years in the Peace Corps. He wanted to get into newspapers — a career he'd been pursuing since high school — and got hired at the Chicago Sun-Times. They soon dispatched him to Springfield to cover the Illinois Constitutional Convention.

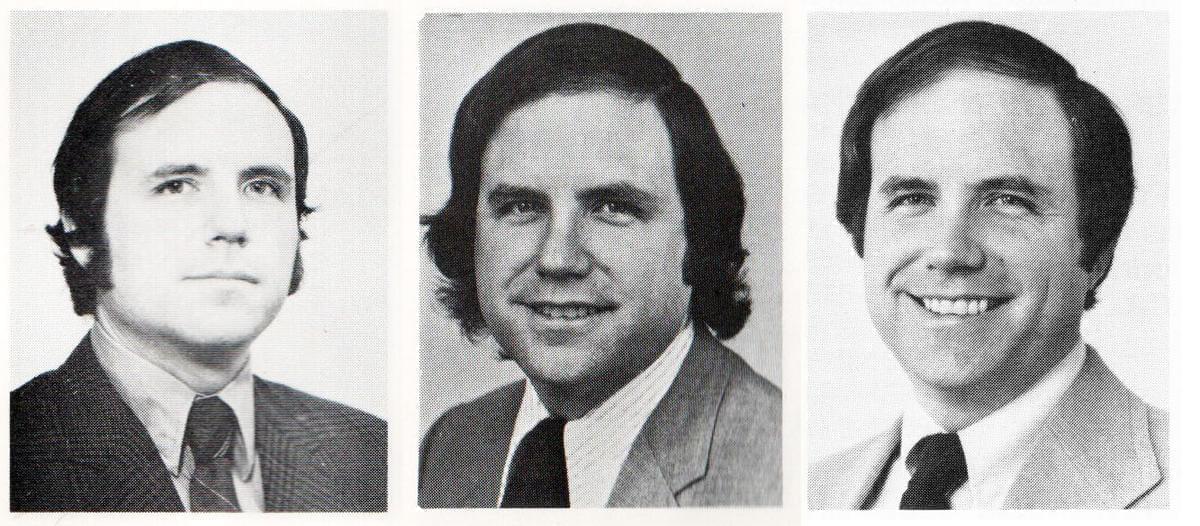

Portraits of the journalist as a young man: Charlie Wheeler's Blue Book photos from, left to right, 1971-72, 1973-74, and 1975-76.

“When I first started the Press Room was located in the state Capitol, in the west wing in what had formerly been the Illinois State Library,” Charlie said. “And there were several dozen cubicles, each of which had one or two reporters, with typewriters. So you'd walk in and hear the typewriters chattering away.”

Charlie's been covering the Illinois Statehouse ever since.

“So it was a pretty lively place,” he said. “And it was a major, major operation. There were probably 40 or more full-time reporters back then.”

In his five decades as a reporter and teacher of reporters, Charlie has seen the Statehouse press corps strangled by twin forces of technology and malevolent ownership.

He reflected on all this in a speech in April at a hall of fame reception for the University of Illinois Springfield’s Public Affairs Reporting program, which Charlie led from 1993 until his retirement at the end of August.

Here he is talking to a room full of colleagues and former students about how he landed in Springfield:

After the convention was over, they needed somebody to come down and cover the legislative session 1971 I was the only guy in his city room who'd been to Springfield before and was willing to go back.

But when I started, there were five daily newspapers in Chicago, all of whom had a bureau here in Springfield. There were two St. Louis papers. They had a bureau here in Springfield, to wire services with the bureau. The network affiliates here in central Illinois had a bureau. There were a couple of radio networks plus local radio stations had bureaus. And even WGN-TV had a bureau, a full time guy down here in the State Capitol. That is all changed.

Charlie says one of the keys to this bounty of coverage was the fact that most newspapers were private companies owned by families.

That model is pretty much gone everywhere. They've become more — well they went through a phase when they were public ownership, and now they're owned by — a lot of are owned, the big media companies, are owned by private equity investors, for whom putting out a newspaper is no more different than making dog food or soap flakes. They have no sense of community. It's all about the bottom line.

For the Wheelers, journalism was the family business. Charles N. Wheeler (second from right, Charlie's grandfather), covered the 1907 session of the Illinois General Assembly for the Chicago Inter-Ocean.

“I think there's a big distinction between a family-owned newspaper, and one that's owned by some private equity group, located maybe hundreds if not thousands of miles away from the community that the newspaper ostensibly serves,” Charlie said in an interview.

“As a matter of fact, the publisher of the Joliet Herald-News, when I was a paper boy, was on my paper route. And so they were familiar with the community,” he said. “Nowadays, you have absentee ownership.

“I liken private equity firms who come in to the people who run chap shops, with automobiles, stolen automobiles, they break them down and sell the parts,” Charlie said. “In my mind, these equity investors come in, they'll buy up some community newspaper, they'll cut costs everywhere by laying off reporters, laying off or outsourcing the printing, so you no longer have printers and pressmen, and ultimately, they declare bankruptcy and fold the paper.”

Greedy, absentee ownership is only part of the story. Evolving technology also plays a role. When Charlie was just getting started, the press room had its own Western Union operator.

“Because back in those days, people filed their stories via telegraph,” Charlie said. “And it wasn't until I'd been there for probably 15 or more years that we switched to computers.”

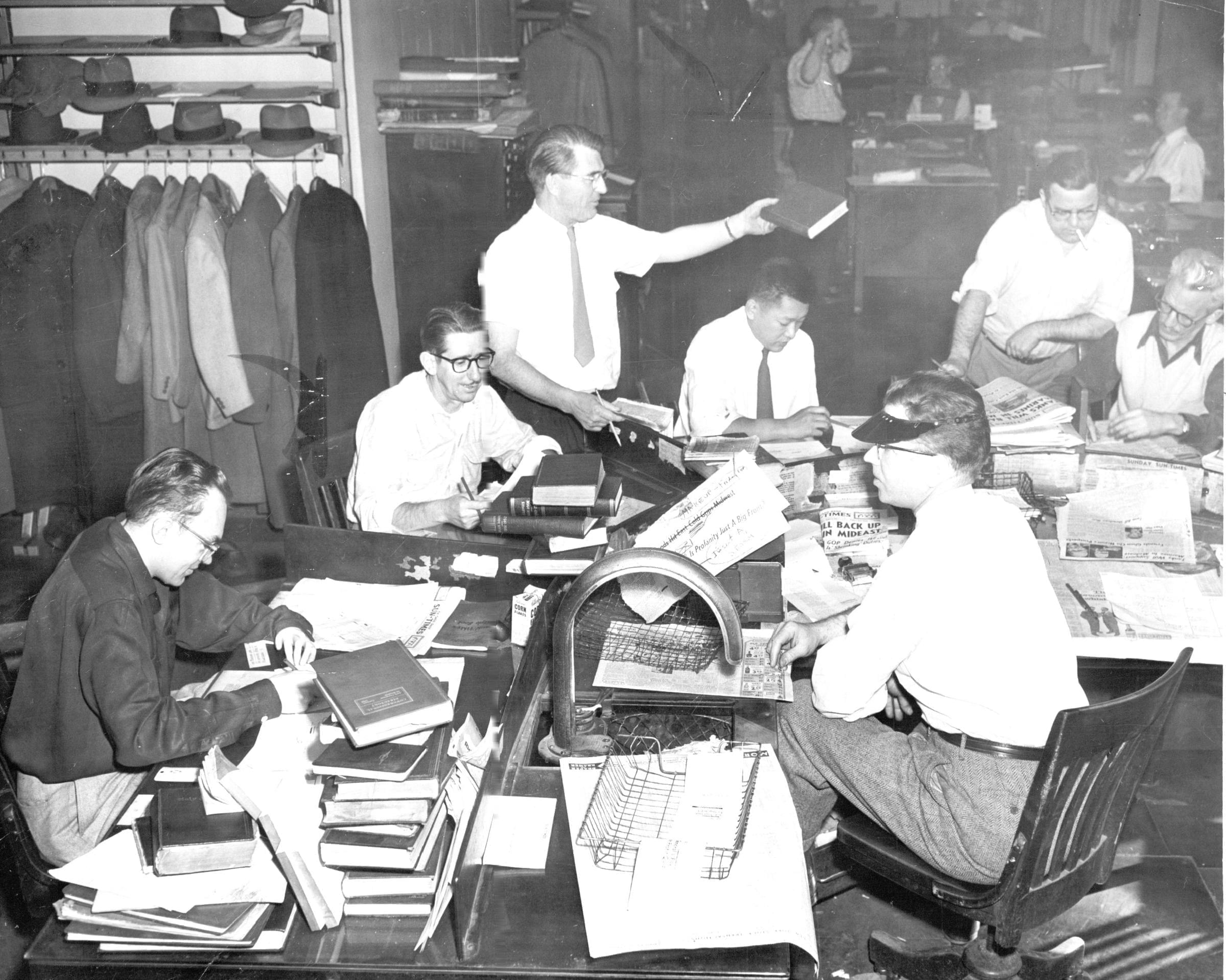

The Chicago Sun-Times newsroom in an earlier era. Charlie Wheeler's father, standing second from right, was a copy editor at the paper.

But the most consequential changes to the media brought on by technology are not in how reporters write and file stories. The more important changes are in how people consume the news. Remember that paper route?

“We delivered papers after school in the afternoon, because most newspapers were afternoon newspapers,” he said. “And then with the advent — the widespread advent and availability of television, people didn't have to rely on the newspaper to get the afternoon news, they could get it more quickly and more up-to-date just by watching TV news. And so gradually, afternoon newspapers became morning newspapers.

"And then it was accelerated, I think, with the advent of the Internet, and the ability to go online and see digitally what happened just moments ago. And that accelerated the decline, I believe, in the print media's circulation and availability,” Charlie said.

There's also CraigsList and eBay supplanting classified ads, and the shift of advertising from newspapers to the likes of Google and Facebook.

Put it all together, and according to an analysis by the Boston Globe, over the last 20 years, the newspaper industry has endured steeper job losses than coal mining.

And we all are familiar with that. We've all seen our shops been reduced. We've all seen papers that used to publish seven days a week now do six or five.

“I find it sad. And I find it troubling,” Charlie said in the interview. “Because I think the success of our system depends on an informed public, not people who get their information from somebody's Facebook post, because he heard it from his neighbor who overheard it at the barbershop three weeks ago — but from people who are there reporting, and people who are committed to reporting facts, verifying the details of what they're going to report, or to use one of my pet phrases, people who read the bill. They don't write about stuff unless they know what they're writing about.”

So is Charlie optimistic or pessimistic about the future of Statehouse coverage?

"I think it's evolving. And I think we're moving away from the, if you will, the for-profit, corporate driven, all about milking every last dime out of the operation we can to more a scenario, if you will, of public journalism,” he said.

Charlie Wheeler leans on the brass rail on the third floor of the Illinois Capitol. Located near the members' entrances to the House and Senate, it's where lobbyists congregate on session days.

“Here in Illinois, we have an operation called Capitol News Illinois. The purpose is to provide the kind of coverage that once upon a time was covered by bureaus which no longer exist. And it's been phenomenally successful. Now that, to me, is a model for the future. And in a way, it's just like public radio.”

I'm a firm believer in this — how important it is. And I still see myself as a reporter. And I look at you folks who are going to be carrying on this legacy. You're going to carry this forward. And it's going to be on your shoulders that the responsibility will fall to continue to provide the information that people need to be able to govern themselves.

Excerpts from the PAR Hall of Fame speech have been edited and condensed.