Illinois Issues: Does The ADA Work?

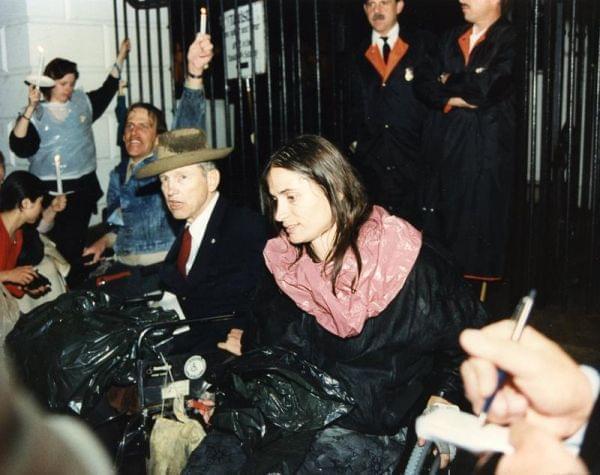

Illinois activist Marca Bristo and Justin Dart, known as the father of the ADA, at a 1989 march to the White House to call for passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act. (Photo: Yoshiko Dart/Access Living)

Twenty-five years after the landmark federal law, people with disabilities in Illinois still have trouble getting hired.

Bob Peterson wants to work in the community rather than in a sheltered workshop for people with disabilities. In that Aurora program, he spends five hours a day putting components for gutters into plastic bags. Rather than a set wage, he is paid by the piece.

Peterson has a learning disability and cerebral palsy limits his mobility. The Naperville resident says he has applied for jobs and been told the prospective employers would call. They did not.

He is not alone. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which outlawed hiring discrimination and created greater access in dozens of ways, is in its 25th year. Through the ADA, improvements including wheelchair lifts and curb cuts were created, as was technology that assists those who are deaf and blind. Efforts for inclusion in education and living arrangements have expanded.

But advocates for people with disabilities say the advancements have not been as great in employment. This is not only because of stigma or discrimination. There are national policies that work to limit pay and discourage employment for people with disabilities. But the tide may be starting to shift with a movement demanding that employment be the first choice for occupying the time of people with disabilities.

Bob Peterson wants a job integrated into the community instead of the day program where he does work for which he is paid by the piece.

“I think there’s still some real issues with respect to people with disabilities getting hired,” says Barry Taylor, a vice president at the Chicago-based advocacy group Equip for Equality. “I think that some people thought that when the ADA was passed, it would result in increased employment rates for people with disabilities, but the employment rate hasn’t really changed significantly for people with disabilities over the last 25 years.’’

Marca Bristo, a long-time disability activist who was involved with the writing of the ADA, says she knows it is hard for a younger generation to imagine a world before the act. Bristo is also president and CEO of Chicago-based Access Living, which she founded in the late 1970s. “The kids who’ve grown up, who’ve been born since 1990, haven’t really known a world other than the post-ADA era, so it’s hard for people to go back in time and remember it,’’ says Bristo, who became disabled after she broke her neck in a diving accident in 1977. After that, Bristo says she lost her job, her home and her health insurance because she could not walk.

“The ADA made a statement that to be disabled in America, we had the right to the same opportunities that other people take for granted. And so the kinds of things that have changed are, first, the policy, that’s really important. Instead of exclusion and segregation and paternalism we’re replacing those ideals with inclusion, independence and empowerment because we’ve acknowledged in federal law that disability is a normal part of the human condition.”

Bristo says that prior to the ADA, “Employment was impossible to get, employers could just look at you and say, ‘No, we don’t hire people who use wheelchairs,’ or ‘I’m not sure I want to hire a person with epilepsy for this service position because what if they had a seizure? They might frighten my customers.’” She says employers could issue such blunt rejections and there was no legal option at the federal level for people with disabilities to push back. “Many people with many disabilities —mental illness, developmental disabilities and physical disabilities — were just sort of institutionalized as the first option.’’

Though significant improvement has occurred in the workplaces of people with disabilities, Bristo says, “where you see a barrier for people with disabilities is for people getting into the workforce. People who aren’t currently there, we haven’t seen the employment rate change very much. And that still needs attention.” In Illinois, 9.2 percent of the state’s non-institutionalized population between the ages of 21 to 64 had at least one disability, according to 2013 Census numbers crunched by Cornell University. Of those people, 37 percent were employed and 27 percent earned less than the federal poverty line.

Several of the people with a disability interviewed for this story can attest to difficulties in getting hired. Ann Ford, executive director of the Springfield-based Illinois Network of Centers for Independent Living, had polio when she was a child. She clearly remembers an age when it was common for words like “cripple’’ to be used.

When she was in her early 20s, a counselor set up an interview for anentry-level clerical job. At the time, Ford had braces and used crutches. She says when she went for an interview, the potential employer looked her right in the eye and said, “‘I can’t hire you because you are crippled.’”

Amber Smock, the advocacy director at Access Living, cannot hear. Decades after Ford’s experiences with discrimination in employment, Smock ran into anti-disability bias, too. But Post-ADA, she can take action.

Amber Smock of Chicago, who is deaf, says since the ADA, she would be able to seek recourse if she was discriminated against in the workplace.

“If I were applying for a job and somebody discriminated against me, I would be able to hold them accountable,” Smock says. “That has happened in the past. Before I was working (at Access Living,) I was looking for work at a publishing company. I interviewed for a job as an assistant editor and once they found out I couldn’t hear very well they … phoned and said ‘we’ll call you back, maybe there will be some other kind of job opening for you.’ And that’s a pretty common thing. It depends on how badly you want you want the job, whether or not you’re going to pursue filing a claim and so forth. So I have ways to be able to make sure that my rights are upheld if I’m looking for work.”

Of the societal reasons that affect limited employment of people with disabilities, discrimination is hardest to prove, says Andrew Houtenville, an economics professor and research director of the Institute on Disability at the University of New Hampshire. “It’s right out of the gate. It’s before you get hired. Once a person’s hired you don’t hear so much about ‘they didn’t support me in doing this,’ unless a person’s disability increases in severity.”

Research contradicts any basis for bias, he says. “I can tell you what the literature generally says about people with disabilities, is that they have lower rates of absenteeism and higher rates of loyalty, so they’re more likely to stick to a job. Job turnover is a big deal to companies, you know it’s expensive to replace people, so if you have people who once they find a job they like they stay longer, so there’s this idea that people with disabilities are more loyal workers.”

There are many reasons, including diversifying the workforce, why it makes sense to hire people with disabilities, says Jorge Perez, executive vice president of Professional Diversity Network Inc., which works to create access to employment opportunities for varied types of professionals.

Most employers are more than interested in hiring people with disabilities, but sometimes the potential for it is thwarted by misperception and misunderstanding, he says. Among benefits of dealing with the disability community are that doing so widens the hiring pool, and, once hired, the output of people with disabilities is greater than the average worker, Perez says. “If you don’t have a … strategy to be able to, as an employer, to hire people that might have a disability, you’re missing out on 10 percent to, in the future, probably 18 percent of the population that you should be able to tap into. “

Having employers who are supportive can make all the difference, Bristo says.

Prior to her injury, Bristo had been a labor and delivery nurse at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, “but I’d only been there for just under a month, I had previously been at Rush. I had just switched jobs and my health insurance hadn’t kicked in yet, so I was without insurance [and] lost my job.”

Marca Bristo coordinated the grass-roots effort at the national level working with people who were crafting the ADA legislation. “We would review the drafts, the different sections of the bill and provide them feedback.”

But the director of nursing for Northwestern’s Prentice Women’s Hospital later asked if she wanted to return to work. “I had been out of work at the time for four or five months and you don’t know how quickly you begin to internalize all these messages that society lays on you. My answer still startles me: I told her I couldn’t work, and she said, ‘Well why don’t you come back in, and we’ll talk about it.’ She took three jobs apart and put the job descriptions back differently, taking tasks I couldn’t do and putting them in somebody else’s description and taking tasks I could do out of theirs and putting it in mine, and I went back to work.”

A federal Department of Labor rule created in 2013 sets a goal that 7 percent of the workforce hired by federal contractors and subcontractors be made up of people with disabilities. “I think [the rule] has stimulated business to step up in a new way,” Bristo says. “Many are really stepping up and seeing this not just as an obligation but as good for business and good for the bottom line.”

Meanwhile, several major businesses and nonprofits teamed up for a six-month-long initiative in Chicago to celebrate the ADA anniversary. Called ADA 25 Chicago, it includes efforts to create a leadership institute to expand access to civic engagement, such as serving on public boards, for people with disabilities. It also creates a network to broaden inclusion in business. Sponsors of the program include The Chicago Community Trust, Walgreens and Exelon.

Houtenville says another contributing factor to the low-level employment among the state’s disabled residents is that support services often have the end result of discouraging work. He says the country’s strategy for helping with a disability is spending on income support, leaving little funding for employment services.

“In order to get supported in the United States, you need to say you can’t work. People with partial disabilities that are severe but who have work capacity go on these programs and get stuck there,” Houtenville says. He notes that insurance coverage is often tied to Social Security disability benefits. “If you go back to work and lose your social security, you’ll also lose your health insurance benefits … With the rising cost of health care, that’s even more important.”

But not all policy is bad, advocates say. They hope advancements will occur because of a national Employment First movement, which argues a job in the community should be the initial option for people with disabilities once they are out of school.

Illinois, one of 30 states with an Employment First effort, adopted a law in 2013. Taylor, of Equip for Equality, says the law requires that “the first option for employment for people with disabilities in Illinois should be integrated, competitive employment, as opposed to them being relegated to segregated workshops and being paid a sub-minimum wage.”

He adds: “That’s a real turnaround, because Illinois has relied on sheltered workshops and sub-minimum wage for a long time, and this is saying that that should be the last option as opposed to the first option.”

So-called sheltered workshops offer work and training to people with disabilities in settings that can be more accommodating than a standard workplace, but often come with much lower wages. The 1938 law that established the federal minimum wage included people with disabilities among the classes that would not have to be paid minimum wage under certain circumstances.

“Without competitive, integrated work,” says Rene Luna, a community development organizer for employment at Access Living, there is “an element of exploitation that occurs.” He calls paying people less than minimum wage “a feudal system that needs to be replaced with a modern one.” Luna is also the creator of the advocacy group Disabled Americans Want Work Now.

Advocates say the new law has made some difference. “We’re seeing a renewed effort in Illinois to make employment the first option for students in special education and adults in community programs right now,” says Tony Paulauski, executive director of the Arc of Illinois, an organization that advocates for people with intellectual disabilities.

Becca Burrows of Bridgeview is both a client and a worker at Garden Center Service’s satellite office in Chicago.* The agency, based in southwest suburban Burbank, serves adults with mild, moderate and severe intellectual disabilities. “I couldn’t ask for any other type of job. I love what I do for the company,’’ says Burrows, who has worked in the front office of the facility since 2011.

Her duties include answering phones, greeting visitors, making copies and handling mailing of the agency’s newsletter. She is paid minimum wage by the nonprofit agency. “I’m a staff person now. I’ve been working very well ... I ask them every day what they need me to do, and I’m fulfilling my position.”

The benefits of working are psychological, financial and societal. “Employment carries with it benefits, meaning real health-care benefits, unemployment insurance benefits, the ability to interact with your nondisabled peers and develop a social network outside of the disability community,” Paulauski says. “Segregated settings certainly hinder real, inclusive communities.”

Bristo remembers how she felt when she was offered new job at Northwestern. “She really got me into feeling productive and having a life, and it’s through that that I ultimately was challenged to get into the disability rights.”

Research has shown that two-thirds of people with intellectual disabilities have a stated preference for having jobs integrated in the community, while the integrated employment rate for people with intellectual disabilities hovers at about 20 percent, says David Mank, director of the Indiana Institute on Disability and Community at Indiana University.

But not everyone who is intellectually disabled is suited for community employment, says Allison Boyle, day program manager at the Garden Center Services’ Chicago site. “I think it could be as simple as someone being shy or someone who’s just not comfortable — some people who don’t have a lot of the intellectual abilities to do it; people who maybe have severe intellectual disabilities will not do well in a job. We have a couple people like that here. We have a lot of people who have autism, who have sensory issues or problems with light. You have to find a good fit for those people if you’re going to put them in a job market.”

She says not all policymakers understand this range of needs and abilities among her clients. “When it comes to the job stuff … we have to look at each person individually,” she says. “There’s a push to get everyone into jobs, but we have to look at our clients and know them and know what works best for them. For some people, yes, it is a job, and it’s really great, and it’s what we want. But for some a job isn’t good for them, or they maybe need a lot more training. I think it’s something that’s so individualistic that people forget that.”

Paulauski says there will always be a small segment of the population that isn’t suited for employment — but support systems need to be established to help those who want to bridge to it. “That was the reason for sheltered workshops was to be a stepping stone to employment, and that’s not the case in Illinois or across the nation,” he says. “Usually what we find is that people have been there most of their lives.”

Bob Peterson, in the wheelchair, and Tony Paulauski, who directs the Arc of Illinois, appear at a rally in Springfield.

A special focus should be put on the future employment of high school students, he says. “Long before they’re getting ready to exit the school system, when they exit the school system they should have a job, a real job with benefits if they’re in special education.”

Paulauski says Gov. Bruce Rauner should make the issue part of his agenda. “The new administration needs to make employment of people with disabilities a high priority and there needs to be as a high priority resources allocated to make it more than just a good public policy statement but translate into programs that get people jobs in the community and state government.”

Some, like DAWWN founder Luna, contend the Rauner administration is preoccupied by the state’s budget impasse and has not been as focused on helping people with disability as it could be. (Click here to read a sidebar to this story about the budget's impact on people with disabilities.)

In addition to Illinois’ Employment First law, former Gov. Pat Quinn also signed an executive order last year that called for an Employment First liaison. Taylor points out that the new administration has yet to fill that job.

Veronica Vera, acting spokeswoman for the Department of Human Services, says the governor’s office is still looking for someone to fill the position. In an email, Rauner spokeswoman Catherine Kelly wrote, “The needs of our most vulnerable citizens are very important to the Governor, which is why he has signed a number of bills that will benefit Illinoisans with disabilities.”

Much more has to happen to really get the Employment First movement truly rolling ahead in Illinois, Paulauski says. “First of all, it’s a major policy step forward and that policy needs to be implemented in our school systems [and] in the adult system as well. There need to be the resources available for job training and job coaches to provide adequate, short-term training and assistance to help people not only secure good employment” but have access to transportation and education about how to use it.

But that requires funding. Instead, he says the state is predominantly paying for “segregated care in work centers rather than individualized employment programs.”

His goal? “What’s the unemployment rate in Illinois, something around 6 percent?” Paulauski asks. “I think I’d be happy with a 6 percent unemployment rate for people with disabilities in Illinois.”

*Maureen Foertsch McKinney is a guardian to her brother, a client at Garden Center Services.

Links

- Assuring Care of a Family Member with Disabilities: Legal and Practical Planning

- Obamacare: People With Disabilities Face Complex Choices

- How Workers with Disabilities are Legally Paid Below Minimum Wage

- University of Illinois Services for Students with Disabilities; and “The Ghana Project”

- The Americans with Disabilities Act: Improving Lives and Providing Visibility