Illinois Issues: Little Soldier, Big Mystery

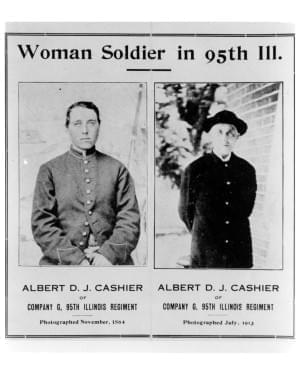

Jennie Hodgers AKA Albert Cashier served in the Company G of the 95th Regiment, Illinois Volunteer Infantry, which fought at Vicksburg. Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

More than 100 years after his death, Civil War veteran Albert Cashier remains a mystery. For three years, Cashier fought hard battles - including Vicksburg, Natchez, and Atlanta - with Company G of the 95th Regiment, Illinois Volunteer Infantry. He was known for his bravery and small size.

Years later, he became known for his long-held secret. Cashier was a woman - Jennie Hodgers.

"All we know for sure is that Jennie Hodgers was born in Ireland and that by 1862 Jennie Hodgers had become Albert Cashier and was in Illinois," says DeAnne Blanton, a "19th century army records expert" at the National Archives and co-author of "They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the Civil War." "When did Jennie Hodgers come to the U.S.? Or did Albert Cashier come? When did Jennie Hodgers start living as a man? We don't know."

Cashier was quiet and didn't share much, according to his comrades, based on their comments in numerous articles about Cashier and in his pension records with the National Archives. When Cashier did share, which was late in life after his secret was out and he became a news sensation, he told conflicting stories. Cashier said he had been a stowaway to America, that he had a male twin and both had been dressed as boys, that his parents' graves were in America, and that he enlisted to be with his lover who was fatally wounded and asked Cashier to dress as a male permanently. None could be verified. (Cashier's lieutenant said, in the May 29, 1913 Rockford Daily Register-Gazette, that he saw or heard nothing to support Cashier's claim of a beau in the company.) Nettie Rose, a friend of the little soldier's, testified to the Pension Bureau that Cashier "would stretch the truth sometimes… and some thought he was half witted."

We know that Cashier lived and worked as a man before the war. Charles W. Ives, second lieutenant of their Company, testified to the Bureau that Cashier was a farm hand for a man named Avery. "(Avery) came in with her when she enlisted…I think Avery did not know her sex." After the war, Cashier maintained his male identity, often wearing his Union uniform.

At Vicksburg, he contracted chronic dysentery, which disabled him for the rest of his life, according to pension records. He appeared to have no family in America and was illiterate. Cashier took odd jobs to survive and got an invalid pension in 1890. He worked for state senator Ira Lish in Saunemin, Illinois, who said Cashier was "entirely alone, destitute, and dependent on the charity" of others, in Cashier's pension records.

While working on Lish's car in 1911, Cashier's leg was broken, according to Blanton's book. The doctor who treated it discovered the secret Cashier had hidden from his regiment for three years. He and Lish agreed to keep Cashier's gender a secret and helped him get into the Illinois Soldiers and Sailors Home in Quincy, where they swore officials to keep Cashier's secret, too. The veteran was 66 years old then and permanently disabled.

At the Home, his secret got out and articles about him appeared around the country for the next few years. His comrades were stunned. Ives, who visited Cashier in the Home, said he was "never more surprised" than when he learned the private's gender and spoke of his "bravery, courage and patriotism," according to the May 29, 1913 Rockford Daily Register-Gazette. After their company repelled the enemy behind its earthworks at Vicksburg, Cashier "jumped up on a fallen tree and yelled at them: 'Why don't you get up, you darned rebs, where we can see you?' They were not more than a block distant and could easily see him. I was acting lieutenant at the time and ordered him down. A storm of bullets swept across there but he was not hit."

When the Pension Bureau heard Cashier was a woman, it launched a long investigation into possible fraud and had investigators interview Cashier's comrades and acquaintances to make sure this was the same person who fought in the war. Robert Hannah, who served with him, testified that soldiers weren't "stripped" when they enlisted "and a woman would not have had any trouble in passing the examination."

Up to 1,000 women did just that during the Civil War, according to Anya Jabour, an historian specializing in women and gender studies at the University of Montana. "It was really a very, very easy thing to do," she says. There were no birth certificates or Social Security cards at the time to identify people. "Somebody who wanted to enroll just showed up at the enlistment office and gave their name. …The recruiting officer looked at the person to make sure there were no obvious impediments to fighting, like a missing limb or a consumptive cough, that would indicate tuberculosis, and that was pretty much it." Many underaged boys signed up and women soldiers, who also lacked facial hair and deep voices, were often mistaken for them.

In the field, it was fairly easy to escape detection. Soldiers wore "pretty ill-fitting uniforms, never got fully undressed in front of each other, slept in their clothes, and often relieved themselves in the woods," Jabour says.

Ives said there was another woman in their regiment, according to the 1913 Rockford paper. She disguised herself and joined to be with her beau. Their colonel had to kick her out, but he couldn't identify her based on appearance. So, he threw each soldier an apple. The woman gave herself away by trying to catch it as if she were wearing an apron.

Albert Cashier, photographed in 1864 and 1913.

"We look back on these 19th century armies and assume they were all male," but women helped them in a variety of capacities, says Elizabeth Leonard, an historian specializing in Civil War women at Colby College and author of "Yankee Women" and "All the Daring of the Soldier." In addition to women disguised as soldiers, "there were women (undisguised) who were laundresses and cooks and nurses attached to regiments." There was no standing army or military infrastructure to provide these services, so "women stepped into the breach." The public didn't always support these women, says Leonard, because most felt they belonged at home. However, "many women soldiers were forgiven if they claimed they served out of love of a man or love of country."

By all accounts, Cashier's comrades supported him, even after his secret was out. They visited "Al" and shared newspaper clippings and current photos of their friend wearing his old uniform.

After developing dementia, Cashier was moved to the Western Hospital for the Insane in Watertown (near Moline), Illinois in 1914. According to the summer 1989 Illinois Historical Journal, Ives visited him and found Cashier "broken" because hospital officials forced him to wear a dress. "They told me she was as awkward as could be in them," Ives wrote. Cashier tripped on the female trappings and broke his hip, which lead to his demise in 1915.

Months before he died, Cashier marched in Moline with the Grand Army of the Republic (for Union veterans), reported the June 13, 1915 Rockford Morning Star. A hospital physician took him to the event in his Union uniform. The veteran "realized she was (participating) in an historic event," the paper reported. Cashier's GAR peers requested he be buried in his uniform "with full military honors in the little cemetery at Saunemin, (Illinois)" according to the winter 1958 Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society.

There were hundreds of known women soldiers during the Civil War and untold numbers of others we'll never know about because they succeeded in hiding their gender, Blanton says. Yet Cashier's case stands out.

While most women soldiers maintained a male identity only during the war, that wasn't true for Cashier. "Cashier's life demonstrates that clearly there had been individuals for a very long time who have been uncomfortable with their assigned gender and have chosen to live a different gender," says Jabour, who calls Cashier "transgender."

In her book, Benton theorized that Cashier lived as a man because it provided greater opportunities for employment and freedom. "Now, I do wonder, perhaps Cashier was a truly transgender person and that Jennie became Albert because that was the identity in his head. This is something I've been thinking about in recent years as I've become aware and educated about transgender issues. Now I wonder if we got it right with Albert."

Illinois Issues is in-depth reporting and analysis that takes you beyond the headlines to provide a deeper understanding of our state. Illinois Issues is produced by NPR Illinois in Springfield.

Links

- Illinois Issues: Online Shopping Court Decision Brings Uncertainty

- Illinois Issues: Black Unemployment In Illinois Tops Other States

- Illinois Issues: Money Machines - How Big Donors Dominate Campaign Funding In Illinois

- Illinois Issues: More Nurses To Help Sexual Assault Survivors

- Illinois Issues: Advocates Argue For Sealing Eviction Filings

- Illinois Issues: Outside The Big Box - Repurposing Vacant Space In Illinois

- Illinois Issues: Which Take On Taxes Lowers Them For Voters?

- Illinois Issues: Gubernatorial Candidates Have Fence-Mending Ahead

- Illinois Issues: What’s On Tap For The State’s Big Birthday Party?

- Illinois Issues: On Y-Block Plans, Governor At Odds With Local Businesses

- Illinois Issues: Is Illinois Ready For A Retail Shift?

- Illinois Issues: Money And The Legal Weed Debate