Illinois Issues: Mental Health Care Cuts Threaten Access

After the elimination of a state grant that helps to fund psychiatric services, Sherrie Crabb and directors of community mental health centers throughout the state are concerned that they soon may not be able to offer core services to others in need - including some medications. Charles Williams

When Sherrie Crabb was a child, a crisis counselor helped change her life.

Crabb’s father had an addiction problem and was abusive to her mother. “I grew up in a home that had holes in the walls from fists being thrown and emergency telephone numbers taped under my sister’s bed just in preparation for that one night my mother may need rescuing,” Crabb told the Illinois House during a hearing last month. That night eventually came, and the girls called the police as they hid under the bed.

The police came with a crisis counselor. The sisters were placed in a foster care and began therapy, which Crabb says helped her heal from trauma. She said the crisis counselor, from the southern-Illinois-based Family Counseling Center, gave her “hope that cycles can be broken, and others like myself can be helped.”

Now, she is the executive director of that same agency. But after the elimination of a state grant that helps to fund psychiatric services, Crabb and directors of community mental health centers throughout the state are concerned that they soon may not be able to offer core services to others in need.

The Psychiatric Leadership Capacity Grant provides funding to community mental health centers in Illinois to help cover the cost of employing a psychiatrist. The money goes to most of the roughly 140 mental health centers in the state. Often, mental health centers do not have a full-time psychiatrist on staff but bring one in for a few days each week or month to meet with patients and prescribe medication.

Illinois is in its fourth month without a budget, but state agencies still have to plan for how they will carry out programs. The Illinois Department of Human Services (DHS) has entered into contracts with community mental health centers for other services, but it simply did not send out contracts for the psychiatric services paid for by the grant.

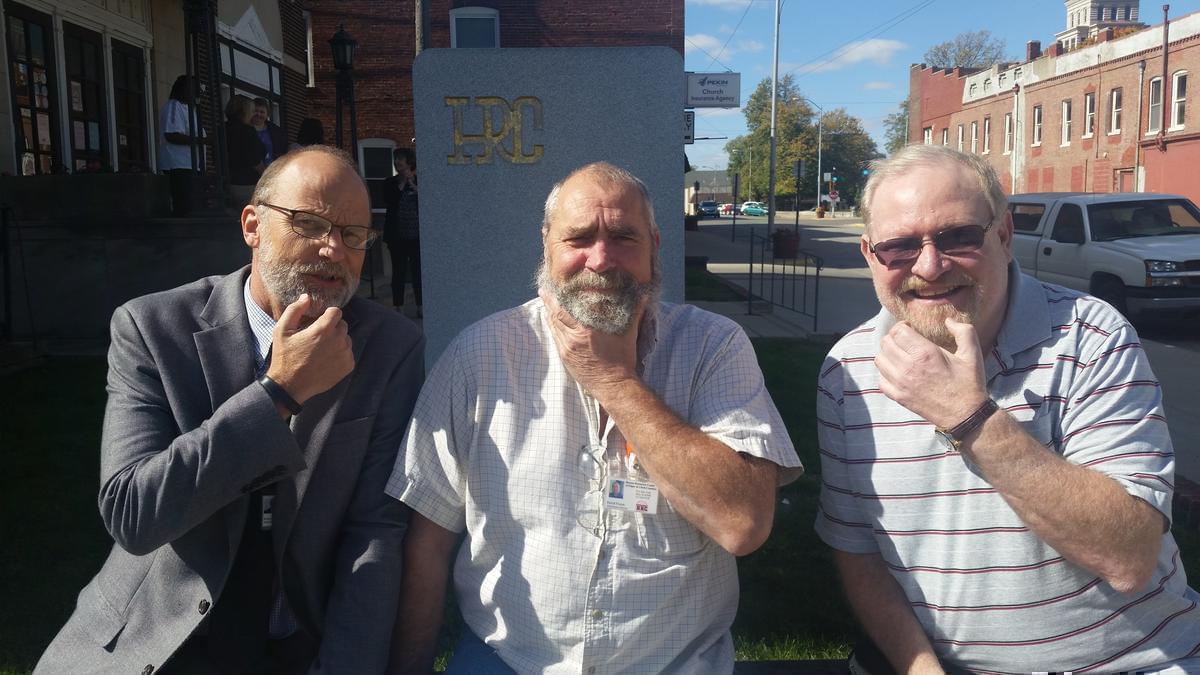

Human services providers are growing beards or wearing flowers until the state has a budget to try and encourage Illinois leaders to come to an agreement. Pictured are staff members from the Human Resources Center of Edgar and Clark Counties.

“There was no explanation or notice from DHS and certainly no suggestion about how community mental health folks should proceed without that funding,” says David Cole, director of the Moultrie County Counseling Center in Sullivan. He says his center gets about $37,000 annually for psychiatric service. “It’s a big cut. The entire line was just crossed out.”

In Fiscal Year 2015, the grant was funded at $27 million. Governor Bruce Rauner called for ending the grant under the budget he presented to lawmakers in February. Still, community mental health center directors say they were taken by surprise when the department essentially eliminated the grant. In recent years, they have seen governor’s proposed budgets call for zeroing out funding in a certain area, only to have some of the money restored in the final budget the governor signed into law.

David King, executive director of the Piatt County Mental Health Center located in Monticello, says he had planned for a 20 percent cut this fiscal year. “My CFO and I, we actually thought we were being proactive and smart budgeters when we only budgeted 80 percent of that money. We knew that there would probably be a cut. We’d kind of read the tea leaves with the budget scenarios that were being discussed back in June. We hadn’t anticipated the entire thing being eliminated.”

King says his center lost about $62,000. Grants for other contracts were reduced, too. He predicts that his center will be operating at a $100,000 loss this year. Still, he says it plans to keep taking new clients. “If you’re in a straight business model, and there’s a product that you’re not going to do anymore because you’re not getting paid for it, well then you can in essence divest yourself of those associated costs. But we can’t do that with psychiatry. …. Our clients have no place else to go. So where else are they going to be maintained on their psychotropic medications?”

The Piatt County Mental Health Center

The Piatt County Mental Health Center has reserves it can tap to cover that shortfall for at least one year, and King says it’s not in danger of closing its doors. “Some agencies that don’t have reserves, who’ve already exhausted those, who are fully extended on their line of credit, they are incredibly vulnerable, and they may in fact close.”

Kenneth Polky — executive director of the Human Resources Center of Edgar and Clark Counties, located in nearby Paris — says that his agency has dipped into its line of credit. But he says it still has enough left to cover payroll for a few months if it had to. “We’re good through this month, and I figure we can probably make November work. But if something doesn’t happen by December or January at the latest, then that could be a real reckoning for not just my agency, but in talking with other administrators, several other agencies as well.”

Polky says some centers are in even more immediate danger. “I’ve been also informed by several that they can’t make it until January. So it’s real concerning to me how devastating this will be to communities throughout Illinois if our elected officials don’t work together and get this resolved.” His agency lost $80,000 when the grant was eliminated, but it was already offering psychiatric services at about a $20,000 annual loss. Even so, he says that the center continues to accept new clients.

“We employ the only psychiatrist that regularly practices in Edgar and Clark County,” Polky says. “You can’t do a very good job as a community mental health center without providing the psychiatric services.”

David King (right) with therapist Jason Woodford

While some mental health centers are still taking new clients for psychiatric care, others have stopped. Pillars, a social services provider that serves the western and southwestern suburbs of Chicago, stopped screening new clients in August. At the House hearing in mid-September, Ann Schreiner, the president and chief executive officer of Pillars, said that the agency had turned away 62 people. “Fewer members of our community are getting the psychiatric services many desperately need,” she said. Pillars is also cutting back on the number of hours it offers psychiatric care each week, leaving 70 current clients in danger of losing access. “It can be three to four months before someone needing a psychiatric evaluation can be seen within our community," she said.

Schreiner noted that the reduction in services comes at a time when several teen suicides have taken place in the community, including the recent death of a 15-year-old girl. “This was another suicide in a continuing string in our community over the past several months — a devastating reality. We’re feeling an incredible urgency to stem this tide and to keep our children alive,” she said. “Treatment works. Without it, we run the risk of very serious consequences, and the loss of life unnecessarily.”

After the Delta Center in Cairo closed in August, the Family Counseling Center, where Sherrie Crabb is executive director, has tried to fill the gaps. But Crabb said the center was only able to hire 35 percent of the staff from the Delta Center, while it took on 75 percent, or about 300, of its patients. Since then, the center has had to cut staff hours and institute some layoffs.

Crabb said her agency is now in real danger of closing, too. “If Family Counseling Center does not receive state payments soon, mental health and substance abuse services will cease to exist in the southern seven counties we serve, and another 61 employees will be laid off,” she said. “Life saving services — the services that ministered to my success as an adult — should not be sacrificed.”

Without access to a psychiatrist, patients cannot get prescription medication. Those taking medicine for their mental illness fear losing the quality of life that treatment gives them. Linda Virgil says her son, who is being successfully treated for his mental illness, called her in distress because he heard about the state’s budget woes and was worried about access to medication. “He totally recognizes what his life was before those medication and before those services, and he doesn’t want to go back there.”

She says his sense of humor, laid-back nature and love of nature and history were all stifled by his symptoms. “He was completely consumed by delusions.” But with therapy, medication and other supports, all those traits have returned. “His medications are absolutely necessary for his recovery,” she says.

But Virgil says the elimination of grants for psychiatry and other cuts to mental health programs worry her. “Families are becoming increasingly anxious. We can’t be their psychiatrists. We cannot prescribe those absolutely necessary medications. … We can’t be their caseworker either. It just doesn’t work. We don’t have those kinds of skills.”

Staff at the Moultrie County Counseling Center participate in the Beards and Blooms for a Budget campaign.

King says that without services, family members of those with serious mental illness will have to make a choice between caring for their loved ones and going to work.

“Somebody who can’t receive care through our system, needs to still be looked after, and those clients are going to be cared for and looked after by their families,” he says. “And if they need a lot of supervision, that means somebody’s going to have to drop out of the workforce. And if [they] have people dropping out of the workforce, they’re not generating tax revenue.”

In many cases, there may not be a family member who is able to adequately provide care without outside support. He says recently a woman “well into her 80s” sought help from his agency because she was looking to apply for guardianship for her mentally ill son. “That’s a tragic circumstance in and of itself. Now, let’s just assume we’re not here to help, and we’re not here to provide therapy, and we’re not here to provide any kind of psychiatric support. What happened to this individual, and what happens to that elderly mother?”

The elimination of the Psychiatric Leadership Capacity Grant follows years of cuts to funding for mental health and addiction treatment services in the state. According to a recent report from National Alliance on Mental Illness Illinois, between the 2009 and 2011 budget years, Illinois slashed $113.7 million in general revenue funding from mental health programs. During that time, only two other states cut more from their budgets for mental health.

Providers say those cuts, along with the closure of psychiatric hospitals, have left many parts of the state ill-equipped to help individuals in crisis needing in-patient care. Polky recounts a recent incident when a patient came to the local hospital in crisis. “No bed could be found in the entire state of Illinois. That poor individual was stuck in an emergency room bed for four-and-a-half days before the problem could be resolved,” he says. “I can’t imagine spending four-and-a-half hours in an emergency room, much less four-and-a-half days. If that wasn’t a challenge to your mental health, I don’t know what would be. It was a horrendous experience for the family. It was a horrendous experience for the individual.”

A placement for treatment was eventually found for the patient, but not in Illinois. “The slap in the face was after all of that — there wasn’t even an Illinois provider that would be able to get this individual in. The individual had to go to Indiana.”

While that patient was in the emergency room, a nurse had to be there to supervise at all times. Polky says that on some shifts, the hospital only has two nurses assigned to emergency care. Pulling one away has an effect on the other patients. “What about the person who just had a car accident and needs urgent care?” he asks.

King says a similar scenario recently played out in Clinton. He says the situation will become even more common if patients throughout the state lose access to their medication. “The more complicated the case the greater the difficulty (to find treatment for a patient in crisis.) So you can only imagine somebody who struggled with a serious mental illness, who then is off their meds because they don’t have a psychiatrist, who now is in a debilitated state, psychiatrically and medically and so on. Who’s going to take them?”

He says many will instead end up in other systems, which are not designed to treat them. “The legal system, jail system, health care providers — they will all feel this. Definitely.”

Illinois Department of Human Services Secretary James Dimas

Since DHS opted not to issue the contracts tied the grants, James Dimas, who heads the agency has made a few comments about the decision at trade conferences for providers. Most recently, at the Illinois Association of Rehabilitation Facilities’ conference last week, he reportedly called the grants unsustainable. Dimas told the group that a better funding model is needed.

“It’s important for all of us to begin to experiment with more cost-effective ways to meet the needs of the community; this holds true for all of the services we provide, including mental health services,” DHS spokeswoman Veronica Vera said in an email. “For example, the more sustainable model for meeting psychiatric needs might include freeing high-priced psychiatrists from administrative duties so they can focus on psychiatric care and using lower priced medical staff to perform administrative duties.”

She says that once a budget is approved, DHS does plan to fund some programs that support psychiatric services. “The secretary and the Illinois Department of Human Services take the needs of our customers very seriously, and we maintain established protocols to ensure that individuals that find themselves in crisis or emergency situations can receive the care they need in a minimal amount of time.”

Josh Evans, legislative director for the Illinois Association of Rehabilitation Facilities, says he thinks the agency is working on solutions. “I do believe that they’re trying to work on plans of how to address this issue.”

But, he says that doesn’t mean that things will eventually return to the way they were. He says some community providers seem to be operating under the assumption that the grants will come back once the gridlock in Springfield is resolved. “I am concerned about those particular situations and that particular belief given that we don’t seem to be any closer to a budget resolution now than we were when it was introduced in February and when we passed May.”

Dimas said at that same conference that he thinks it's possible Rauner could be presenting his budget for next fiscal year before a spending plan is in place for the current one.

The one thing that does seem certain, Evans says, is that if nothing changes, community mental health centers will have to end their psychiatric services. “The most consistent long-term message I have gotten across the board was that basically if this grant goes away completely, these dollars are not put into the system, that [we] will lose access to what limited psychiatry we’ve actually got in this state. So it’s not a question of if. It becomes a question, on a provider-by-provider basis, of when.”

Links

- More Young Adults Get Inpatient Psychiatric Care After Health Law

- Promises To Fix Mental Health System Still Unfulfilled

- Rule Spells Out How Insurers Must Cover Mental Health Care

- Advocates Warn of “Broken” Mental Health System

- Human Services Advocates Address Rauner Spending Freeze

- Illinois Human Services Staff Too Lean