Illinois Issues: No Place To Call Home - Pt. 3

Kasey, pictured in a still from the film The Homestretch, was homeless but has since found an apartment. Producers opted not to use the surnames of the film's subjects. Kasey is an advocate for the LGBTQ community and homeless youth. Courtesy Kartemquin

The state budget impasse could put more young people out on the streets this winter.

Corey Stewart became homeless when he was 18, after his mother died and he found himself struggling to pay rent for the family’s apartment on Chicago’s South Side. “I worked for a temp agency,” he says. “I had my steel-toe boots and I was working, but I just couldn’t swing it — that was too much money. I wasn’t going to school because too much was going on.” And his father, who had never been in his life, was nowhere to be found.

Like many Illinois teens who find themselves without a place to sleep, Stewart began staying at other people’s homes. “I was trying to pay rent on other people’s cribs, and that didn’t work out,” he says. Other times, he slept on the streets.

“If I weren’t mentally stable, I probably would have lost it,” he recalls. “I probably would be doing some time in jail or something like that. It’s harsh out there. You’ve got to worry about bullets. The police. You know what I’m saying? The weather. There’s a lot of stuff you’ve got to worry about. It ain’t no walk in the park.”

The fallout from the state’s current budget crisis could leave more young people like Stewart on the streets this winter.

Stewart, who is now 22, was staying recently at Ujima Village, a 24-bed shelter in Chicago’s Grand Crossing area for homeless people who are 18 to 24 years old. It’s where he went for a bed to sleep; dinner and breakfast; a place to shower; and advice on getting his life back on track. “The staff here, they cool,” he says. “I get along with them and the program at Ujima is very informational. They give you information on a lot of things, and I take heed to it.”

But Unity Parenting & Counseling Inc., the nonprofit group that runs Ujima Village, hasn’t been getting state funding for the past half-year, because of the standoff between Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner and the Democratic leaders of the Illinois General Assembly. Like other nonprofits around the state that help homeless youths, Unity is uncertain how long it can continue providing the same level of services.

A. Anne Holcomb, supportive services supervisor for Unity Parenting & Counseling Inc., was once homeless herself.

“We almost had to close,” says A. Anne Holcomb, supportive services supervisor for Unity. “We actually had informed staff in August that we had no more funding as of September 1. We tried to find other places for the youth to go in that event. But the reality is most of the emergency shelters are state-funded. And the transitional housing programs are too. So there wasn’t really any other place that was secure. We couldn’t find an option. We only have 374 youth beds in the city.”

The group got a reprieve when the city of Chicago stepped in and provided temporary funding — in the hope that those state funds will eventually show up.

Even if a budget is eventually approved, the Rauner administration has proposed cutting spending on services for homeless youths — from $5.6 million in the 2015 fiscal year down to $2.5 million in the current year. About 1,300 young homeless people would lose services and shelter as a result of such a cut, according to a report by the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless, Housing Action Illinois and other advocacy groups.

“They shouldn’t do that because that’ll break people’s spirit,” Stewart says. Shortly after he was interviewed for this story, Stewart left Illinois to pursue a housing opportunity in another state.

“This is the only place we feel safe,” says Deshawana Perrin, an 18-year-old who stays at Ujima Village. “I feel like this is home for me. ... Some of us will be hooked on drugs by the time you open another shelter. ... This is like a family to us. If they take this, we won’t have nobody. We’ll be living in boxes and getting locked up.”

Chicago Public Schools counted 20,205 students who were homeless at some point during the 2014-15 school year, including 2,622 who were unaccompanied — on their own without the support of parents. Meanwhile, the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless estimates Chicago has about 11,500 homeless people from 14 to 21 years old. Statewide, 25,000 youths are homeless and unaccompanied, the coalition estimates.

“A lot of youth who are homeless don't even think of themselves as homeless. That label is not a label that they want to put on themselves,” says Anne de Mare, who co-directed The Homestretch, a 2014 documentary that followed three Chicago teens struggling to find places to stay as they strived to graduate from the city’s public high schools.

“The reasons they become homeless often have to do with abuse in the household — physical, sexual abuse, substance abuse of a parent,” says Julie Dworkin, director of policy for the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless. Young people living on the streets also include a disproportionate number of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender youths, who “come out to their families and are pushed out of the home,” she says. And the homeless population also includes many pregnant teens, she adds.

Family conflicts are the most common reason why teens become homeless, says Russ Mullett, supervisor of runaway and homeless youth programs for Community Elements, a nonprofit in Champaign. “They reach 18. They’re their own guardian, and the parents say, ‘You gotta go,’” he says. “We’ve had kids who get into fights with their parents and then the police are called.”

“A lot of time these youth end up falling through the cracks of the child welfare system,” Dworkin says, noting that young children often become wards of state if they’re abused or neglected, overseen by the Department of Children and Family Services. But, she says, “If you’re a 16-year-old or a 17-year-old, it’s unlikely they’re going to open a child welfare case on you at that age. … They just don’t get into that system and end up on the streets.”

Foster children typically leave the state’s care when they turn 18, but DCFS offers a few years of extended foster care to some who lack permanent homes. Rauner has proposed eliminating this extended service as part of his budget cuts, which he called “difficult but necessary choices.” Dworkin says Rauner’s proposal “would put those wards at serious risk of homelessness.”

Schools offer some refuge to homeless youths, says de Mare. “It’s very often where they have their only hot meal, where they have a caring adult, where they have a circle of friends and some kind of stability. The goal of graduation is a big motivator. And then it’s very strange, when the next day, you’re just left with your life and all of their support network vanishes, essentially.”

The filmmaker says she came away from the experience with an appreciation for the work being done by social-service providers and Chicago Public Schools’ liaisons for homeless students. “We know what works to get young people get back on track,” de Mare says. “There's a lot of really smart, dedicated people. But the capacity to handle the number of young people at crisis is just pathetic.”

Over the years, the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless has successfully lobbied for changes in state laws that affect young homeless people, Dworkin says. As a result, a special licensing standard was created for shelters that serve homeless youths. Before that, she explains, “You weren’t allowed to shelter a homeless youth. It was considered harboring a runaway.” Another law was changed so that minors can’t be charged with prostitution, Dworkin says, noting that some homeless youths turn to prostitution out of desperation.

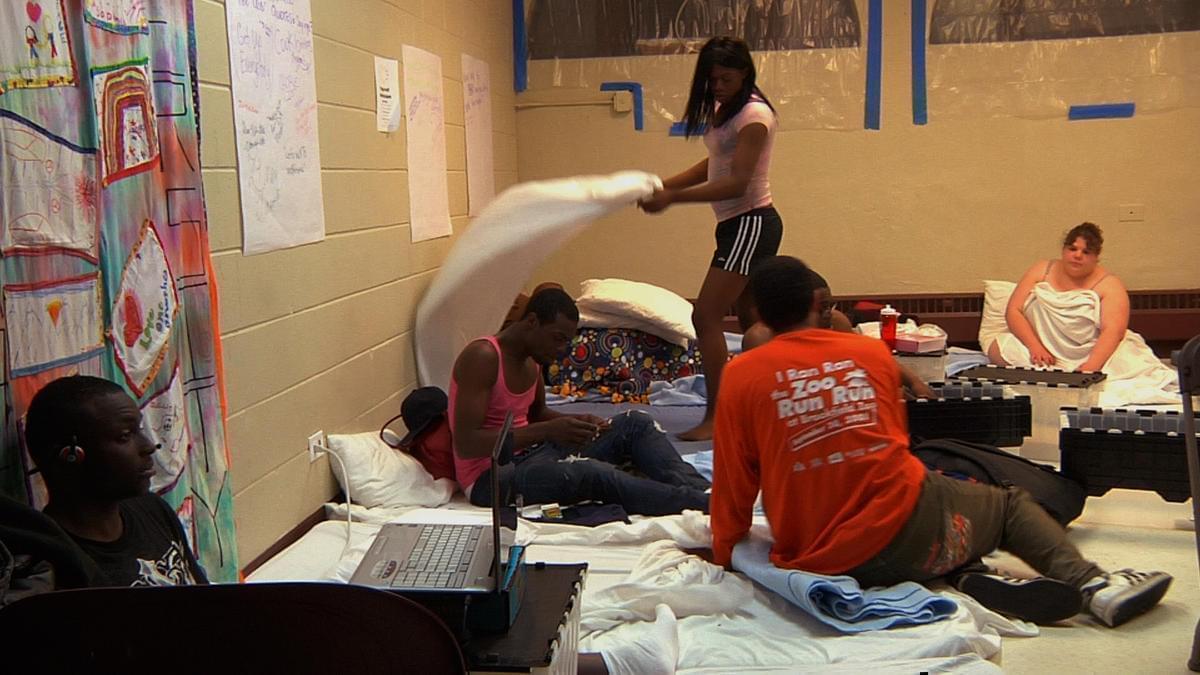

A Chicago shelter is pictured in the film The Homestretch.

Holcomb used to be homeless herself — first as a teenager in Ohio and later as a college dropout squatting in an abandoned building in Indianapolis, when she considered resorting to prostitution, she says. “But one of my street family fell into that, and she ended up killing herself because she couldn’t live with it,” says Holcomb, who’s now 54. “I always think that her death was kind of my life. If I wouldn’t have seen what happened to her, maybe I would have done that. I don’t think I’d be on the planet today if I would have done that.

Not everyone acts sympathetically when they encounter young homeless people on the streets. “People don’t want to see that,” Dworkin says. “They don’t want them sleeping under viaducts. It’s like: ‘Don’t want to have to witness this.’ And homeless youth, I think, can be particularly unsympathetic, because (some people) just think: ‘Gang-bangers. Trouble-makers.’”

“It’s just really hard, because there’s not a lot of people that really see you as regular,” says Erin Robert Conception, a 22-year-old Chicago man who became homeless in his teens, after his mother died. “Sometimes you do get judged. But I see it like this: If they judge you, they don’t know what they’re talking about. Because they don’t know what you’ve been through or what you’ve seen.”

Conception has been staying lately at Ujima Village. “Without these programs like this, I don’t know — I’d probably have been dead somewhere, honestly,” he says.

Another young man staying at the shelter, Forrest Dix, says, “I’ve been coming to places like Ujima for a year, in and out, so I can focus on my career goals. These places provide resources to us to do better for ourselves.”

On a recent Monday night, Holcombe picked up fried chicken at a grocery store and served it as dinner for the kids at Ujima Village. After some of the youths performed hip-hop in the basement, she handed out Ventra cards they could use for CTA bus rides.

The neighborhood around this shelter “is a social service desert and a job desert and a food desert,” Holcombe says. “If you don’t have a bus card, where are you going to eat? We serve dinner and breakfast here. They’ve got to go somewhere to get lunch.” She notes that social workers are available at a daytime drop-in center, where youths can get advice on housing, jobs, education and mental health.

But she adds, “The drop-in center is across two gang lines, so I don’t encourage people to walk.”

Ujima Village is adding lockers where homeless youths can store their belongings — part of a $100,000 initiative funded by the Pierce Family Foundation, the Polk Bros. Foundation and the Knight Family Foundation. Holcomb knows from her own experience as a homeless youth how important it is to have a place for keeping stuff.

Erin Robert Conception, a 22-year-old Chicago man who became homeless in his teens, after his mother died. He is pictured at Ujima Village, a homeless shelter.

“I put my Social Security card and birth certificate in plastic bags,” she says. “And then I dug a hole behind that abandoned building, and I buried it. If I wouldn’t have buried my ID, I would have lost that — and then how can you get a job? You’ve got to have ID to get a job.”

In addition to Ujima Village, Unity Parenting & Counseling runs Harmony Village, a 28-unit facility with apartments for teen moms, young married couples and LGBTQ couples. “Our wait list right now is over a year,” Holcombe says. And she worries about whether that program can continue housing its 60 residents without an infusion of state cash. “We’re short $185,000,” she says.

Although the program is eligible for funding from U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, that requires matching money from the state, she says. “To get that $200,000 from HUD, we have to have a state match.”

Over the years, the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless has pushed for the state to increase its annual funding for emergency shelters, longer-term transitional housing and outreach programs for homeless youths. “Before this whole craziness with the budget, it was up to $5.6 million,” Dworkin says.

The state is in its six month without a budget, with Rauner insisting on changes in law to reduce the power of unions and benefit businesses — proposals rejected by the Democrats who hold a supermajority in both houses of the legislature. In the absence of a budget, the state has continued paying some of its bills, such as employee salaries. But the checks that would normally go to social service agencies helping the homeless are among the bills not being paid.

Kasey drags her belongings from place to place as pictured in The Homestretch.

“No one on either side of the aisle wants to see people who are homeless not having their services provided,” says state Rep. Patti Bellock, a Hinsdale Republican who’s the House GOP’s chief budget negotiator and the Human Services Appropriations Committee’s minority spokeswoman. “I’m very concerned about it.” But she adds, “We have to look at the entire budget. The people of the state of Illinois are tired of the status quo.”

Ralph Martire, executive director of the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability, a bipartisan fiscal policy think tank in Chicago, says there’s more political pressure to maintain state funding for education, health care and public safety than there is for social services.

“It’s the very first thing that gets cut,” he says. “Frankly, being fiscally bankrupt encourages politicians to make the very morally bankrupt decision of balancing the budget first on the backs of the most vulnerable people in our state.”

More than 4,000 youths have been affected by service reductions across the state, according to a survey of service providers conducted in late November by advocacy organizations. Many of those groups have also cut back on accepting new clients, affecting about 2,300 youths, the survey found.

“There’s a certain point after which you just can’t continue to operate on the wing and a prayer that someday you’re going to get money,” Dworkin says.

The Springfield-based Illinois Coalition for Community Services reached that point in September with its four-bed shelter for homeless youths in Charleston. “We had to shut down our homeless shelter, due in part to the budget impasse,” says Jason Gyure, executive director for the nonprofit. “We’ve had to turn people away.”

The group is still providing other services for at-risk teens in Charleston, but it hasn’t received any of the $560,000 that the state owes on its contract for those services, Gyure says. “Our staff is overworked,” he says. “We’re fortunate that we work with such dedicated individuals, who find that mission so important they’re willing to make those sacrifices.”

Despite the delay in state grants, Community Elements has managed to continue offering services. The Champaign youths getting help from Community Elements often lack high school diplomas. “So when it comes to employment, they’re looking at fast food, housekeeping, those kind of jobs,” Mullett says. “Employers don’t tend to hire our clients full time, only part time. So they just don’t make enough money to make it.”

Community Elements pays rent for eight people to stay in apartments, and it runs an emergency shelter where up to six homeless youths from 11 to 21 years old can stay. It also helps young people find housing and jobs, teaching life skills such as how to dress for a job interview.

“So many of our kids have this mindset that state benefits are just a way of life rather than a temporary assistance,” Mullett says. “They’ve grown up with it and they just think, ‘Oh, I’ll just get my food stamps for all my life.’ We try to show them that’s not the goal. It’s to be self-sufficient.”

Anthony, who grew up in foster homes, struck out on his own at the age of 14.

Service providers say they’re saving the state money in the long run. The average annual cost of providing housing and services to a homeless youth in Illinois is $16,700 — including $1,953 from the state, with the rest of the money coming from other sources, according to a report released this fall by the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless and other groups.

If one of those young people is incarcerated through the state’s the juvenile justice system, it could cost up to $111,000 a year, the report says — or the state could spend for one such youth about $32,000 on foster care, says a spokesman for the Department of Children and Family Services.

“They’re going to end up in jail or as part of the adult homeless system,” Dworkin says. “Whereas right now, we can get in there and intervene and just end homelessness for these young people, so that this doesn’t go on to be their life.”

The bottom line, according to these groups, is that the state could end up spending millions of extra dollars if these young people don’t get less expensive assistance now.

This story is part of a series on homelessness throughout the state. Click here to read the first installment, which focuses on homeless families and education, and here to read the second installment, which focuses on rural homelessness.

Illinois Issues is in-depth reporting and analysis that takes you beyond the headlines to provide a deeper understanding of our state. Illinois Issues is produced by NPR Illinois in Springfield.