Illinois Issues: Rewriting The Rule Book

WUIS

A law going into effect next month will ban zero-tolerance policies in schools and turn suspension and expulsion into disciplinary options of last resort. Districts throughout the state are taking different approaches to prepare for the changes.

Every day at Chicago’s Sullivan High School, Chad Adams has to take a series of pop quizzes. Here’s a sample: Michael and Antonio are walking down the hallway, headed to class. Antonio accidentally collides with Michael. Michael retaliates by punching Antonio.

Should Michael…

a) receive a three-day suspension

b) receive a 10-day suspension

c) tell the school principal a sad story about his mom, then apologize to Antonio and return to class

Here’s another one: Tamera comes to school with a can of mace and a knife.

Should Tamera…

a) be arrested by the school resource officer

b) be expelled for bringing weapons to school

c) hand the knife over to the principal, but be allowed to keep the mace

Adams, entering his fourth year as principal at Sullivan, says the correct answer to both of these pop quizzes was option C — giving the kids a chance to explain what happened, rather than automatically kicking them out of school.

“It’s not black and white. It’s not as easy as zero-tolerance,” he says. “It’s time. It’s building relationships. It’s listening to the kid’s story, and knowing that the story is more important than what happened.”

Tamera’s story was that she armed herself because she has to walk past two drug houses every day on her way to and from school, and the men on the porch had recently begun yelling at her. Adams confiscated Tamera’s knife but allowed her to keep the can of mace for her own protection.

Michael’s story was that he had arrived at school that morning still furious at his mother, who is in the throes of an addiction. Michael was already a powder keg, and Antonio just happened to be the bump that caused him to explode. In Adams’ office, Michael gave Antonio a genuine apology, Antonio accepted, the two boys shook hands and went about their day.

“I’ve found very rarely that sending the kid home to watch Maury helps anything,” Adams says. “So I try to use it as a last resort.”

Adams isn’t some gullible guy, letting the inmates run the asylum. He’s been an educator for 15 years, including three as an assistant principal at Harper High, the infamous West Englewood school where 28 students or recent alums were victims of gun violence between 2011 and 2013.

It was there that Adams realized that teaching kids how to resolve conflicts was “just as important as Common Core, state standards and the learning in any class.” Harper had a “Peace Room,” and Adams spent a week in training to become a “certified circle-keeper” — a title that sounds like it comes with a dream catcher and a tie-dyed t-shirt, but doesn’t.

“It just comes with lots of tears,” Adams says.

When he took over at Sullivan in July 2013, he brought the Peace Room concept with him, and closed Sullivan’s in-house suspension room.

Adams has statistics that show his approach has paid off. When he arrived, Sullivan had been on academic probation for 15 years, and was the lowest-performing high school on the north side of Chicago. Since then, attendance has gone up by 10 percent. Chronic truancy, while still high, has fallen by 20 percentage points. Out-of-school suspensions have dropped from 472 per year to just 67. Graduation rates have jumped from 54 percent to around 70 percent, and the school is now off academic probation.

Sullivan High School Principal Chad Adams sits in the school's Peace Room.

His philosophy and experiences put Adams among those administrators who aren’t losing sleep about the sweeping new school discipline law set to take effect on September 15.

Known as Senate Bill 100, it prohibits zero-tolerance policies and monetary fines, and sets stringent parameters on the use of out-of-school suspensions and expulsions. Under SB 100, such “exclusionary discipline” can be imposed only when a student’s continuing presence poses a safety threat or substantially interferes with school operations. School officials have to document prior efforts to help the student, and provide a re-engagement plan — including an opportunity to make up work they missed — to facilitate a suspended student’s return to class.

The new law doesn’t dictate what strategies districts should use in place of exclusionary discipline. Consequently, SB 100 has produced a wide range of responses among school officials across the state. For a few, like Adams, it’s nothing new. They saw what happens when well-intentioned school officials use suspensions and expulsions as the kiddie equivalent of mandatory minimum sentencing — kids fall behind, get frustrated and dropout rates soar. These observations led them to adopt more nuanced practices years ago. Some other officials are welcoming the law as an excuse to add the support services they had been pining for all along. And some are resistant, focused on preserving as much of their past practices as they can, willing to comply with the letter of the new law, but unsure about how to embrace its spirit.

Springfield: Making Less Of Minor Offenses

Leggings, jeggings, stretchy pants — whatever kids called them, they weren’t allowed at Springfield District 186 unless they were topped with a tunic, skirt or dress that covers the student’s posterior assets. Under older versions of the school’s handbook, punishment for violating the rump-cover code ramped up with each infraction, and could eventually result in an out-of-school suspension. But since tight pants cannot be construed as a threat to school safety, principals are no longer allowed to make girls miss school for simply flaunting their figures.

Jennifer Gill, Springfield schools’ superintendent and the mother of two teenagers, has accepted that reality.

“Wearing yoga pants and getting sent to the office — that’s no longer something where first time you get a detention, second time you get three detentions, the third time you might get in-house (suspension) or the fourth time you’re suspended. That would no longer be a process that we could follow through with,” she says.

State Sen. Kimberly Lightford, the Maywood Democrat who sponsored SB 100, says dress code violations are exactly the type of “minor offenses” that inspired her legislation. She cites a 2012 study that tallied up instructional days missed statewide because of suspensions: 1,117,453.

“And what really made me so unhappy was that 95 percent of those were minor offenses,” she says. “That was the reason why I wanted to pursue discipline reform.”

Since passage of the new law, Gill has ensured that Springfield’s new handbook is scrubbed of harsh consequences for trivial infractions. She built the new edition from model language provided by attorneys working for statewide associations of school administrators. It was further tweaked during a three-hour meeting with community groups, and vetted by the district’s own lawyers. The school board finalized the document over the summer, and top personnel have been trained in its use.

Jennifer Gill is superintendent of Springfield Public Schools.

“I have taken my team here at the systems level, and also included principals, to several legal seminars so that we could learn and grow and understand the law,” Gill says.

She refers to all this policy, procedure and protocol work as the “technical” part of implementing SB 100. Now that it’s done, focus can shift to what Gill calls the “adaptive” part, where she has long said she wants to push the district toward “restorative practices.”

That’s an idea that’s been growing in popularity in both education and criminal justice systems since the 1990s. It’s got nearly as many different permutations as Christianity has denominations, but the basic concept requires offenders to accept responsibility and repair whatever harm they’ve caused, rather than just being punished. Gill sees SB 100’s requirement to plan for a suspended student’s return to school as the first place to implement restorative practices. She envisions a scenario where the suspended student would meet with the adult or classmate who was harmed.

The notion of using restorative practice the way some districts do, as part of a daily routine to prevent suspensions from happening in the first place, is a further goal. But Gill says training employees for such a culture shift takes time. “It’s going to be slow to move forward,” she says. “Perhaps we can chart a road to where we’re really making it so that kids want to stay in school (and) don’t want to do these kinds of things. They feel supported. They feel wanted at the school house — and that’s my dream.”

One element of SB 100 that her principals like is the ban on zero-tolerance policies. Nobody enjoys telling a family that their child won’t get to graduate with friends and classmates, or that their college-prep courses won’t be as rigorous at the alternative school.

“We oftentimes have students get themselves into these situations, and they’re ones that are taking AP chemistry or AP physics,” Gill says. “We don’t have those (courses) at our alternative schools with the same group of kids that are going to push and allow you to learn. So we are often faced with that kid not getting the same level of coursework that they had at their traditional high school, and it’s a real hard message to tell somebody.”

Champaign: The Conversation Starts About Adults

Ninety miles east of Springfield, in Champaign, Orlando Thomas has an entirely different response to SB 100. Thomas’ current title is director of achievement and student services, but he got his start as a middle school language arts and literature teacher. Every year, on the first day of school, he would give each class a short speech he can still recite:

“There is nothing you can do that I can’t handle. You’re 12, and I’m not. So there’s nothing you can do that I’m going to raise my hand or press the panic button, for two reasons. One — this is my show; I’m in control. And two — you’re going to be so engaged. We’re going to have so much fun, that you’re going to be locked on learning. There’s not going to be opportunities for you to be off-task.”

How did his strategies work?

“Zero discipline referrals,” he says. “Ever.”

When problems arose, Thomas tried to find a carrot that would help him avoid using the stick. For example, when kids developed a pattern of coming to class late, Thomas started playing music during the passing period, to entice kids to come in early to catch the tune du jour.

“You have to really think creatively and sometimes outside the box to think about — here’s a problem, let me put myself in the mindset of an 11- or 12-year-old. And what might I do to keep them engaged?” he says.

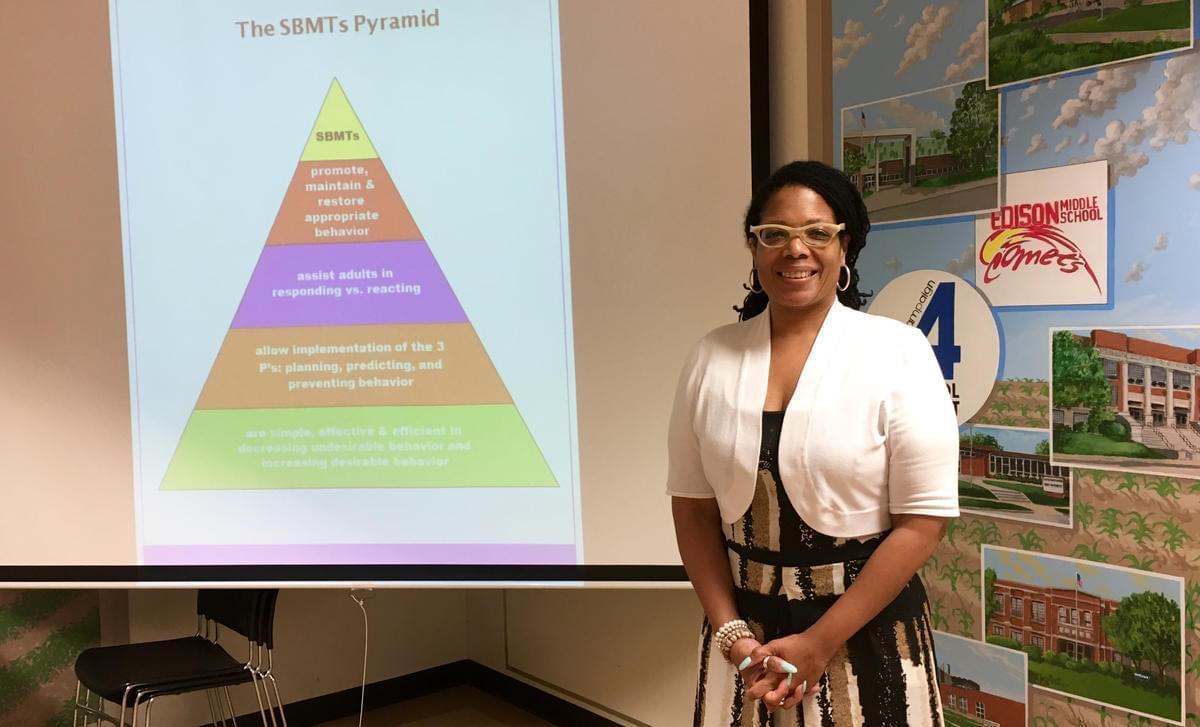

Orlando Thomas is director of achievement and student services for Champaign schools.

He brought this same outside-the-box mindset to Champaign’s Discipline Equity Advisory Committee, which he has chaired for the past five years. The committee meets monthly to look for patterns in the district’s discipline data, and they noticed that just 1 percent of the student body was causing 45 percent of discipline referrals. So three years ago, Thomas got the school board to approve his ACTION plan, which is an acronym for Alternative Center for Targeted Instruction and Ongoing Support. Instead of being sent home, suspended students go to the ACTION center, where they spend the first half of the day learning applicable social skills like conflict resolution. The second half is devoted to academics taught by certified teachers. It’s the students’ actual course work and not just worksheets to keep them busy.

“So a student returns to campus with a game plan, new social skills, some replacement behaviors to eliminate future suspensions, and they go back caught up on school work,” Thomas says.

The same committee noticed a high level of discipline referrals among 9th graders, and established an “early warning” program to intervene with at-risk students in the 8th grade. Any one of three triggers can land a student on the early-warning list: Failing two or more core classes, receiving two or more suspensions or having a daily attendance record under 90 percent. A single staff member is in charge of the list. He invites families on the list to come in and discuss whatever barriers their students are facing, and then connects them to the resources they need to help the students succeed in 9th grade.

Thomas says that over the past three years, discipline referrals for these two groups of at-risk students have decreased by 60 to 80 percent.

There’s one other data point Thomas’s committee uncovered, and this one was not about the kids.

“When we look at our 1 percent of students that are generating a ton of our suspensions, we also have 1 percent of our teaching staff that write the referrals,” Thomas says.

Edna Olive is the founder of a teacher training system called Positive Behavior Facilitation.

For 12 years, Champaign has been offering teachers training in a system called Positive Behavior Facilitation. The name sounds like a dozen other classroom management products on the market, but Edna Olive, the founder, points out the key difference.

“PBF begins with a focus on the individual adult,” she says. “The first order of business is not for you to now analyze and address the kid; the first order of business is for you to analyze and address yourself. … It does not begin with a conversation about children. It begins with a conversation about adults.”

Olive’s mantra is that teachers cannot change students’ behavior. The only behavior they can change is their own.

Her course has been optional for Champaign teachers, but Thomas noticed that the 1 percent of teachers generating the majority of referrals have not opted to take PBF training. Because SB 100 requires schools to provide professional development courses, Champaign school district is now having all elementary teachers take PBF. Next year, all middle school teachers will take PBF, and all high school teachers will take the course in the 2018-2019 school year.

Batavia: Looking Through A Different Lens

Batavia is an upper-middle-class, mostly white suburb in the Fox Valley area west of Chicago. The high school boasts a 95 percent graduation rate, with most kids bound for four-year colleges. Amy Biancheri teaches high school English where she’s a member of the school leadership team. She describes Batavia students as “for the most part, a good group of kids.”

But even affluent communities have school discipline issues, and with the enactment of SB 100, Batavia officials have had to revise the student handbook to eliminate suspension for non-violent offenses.

For example, drug offenses previously triggered a suspension that could last as long as 10 days. Thanks to SB 100, “They come back to school right away,” Biancheri says. “We hired a drug and alcohol counselor who gets them help both inside and outside of school. So it’s more of a treatment. We look at it more as a health issue than a discipline issue.”

Another strategy being used in Batavia is “Paper Tigers,” a documentary the Illinois Education Association is circulating to help teachers be aware of the role childhood traumas — like the loss of a caregiver, family violence or abuse — can play in students’ brain development. At least a quarter of Batavia’s teaching staff has viewed the film, and Biancheri says it has given teachers a “different lens” on the underlying causes of student misbehavior.

“The biggest factor in them being successful is having one caring adult in their lives,” Biancheri says. “And ... if they don’t have that caring adult outside of school, that’s our job, to be that person.”

Amy Biancheri (pictured at right holding the banner) is a high school English teacher and president of the Batavia teachers union.

Biancheri is president of the Batavia teachers union, and she acknowledges that SB 100 was initially met with some fear. But after a full year of discussing the new law and taking professional development courses to learn proactive strategies, educators in Batavia are feeling better, Biancheri says.

She notes that the law still allows for the removal of children who present a safety threat, but she says that situation is so rare that taking children out of schools is generally not the best way to deal with a conflict.

“It’s a law, but beyond that, the spirit of this law is good for kids,” she says. “I know there’s some scary pieces to it, because no one wants to feel like — oh my gosh, this kid is misbehaving, and I don’t have any power to do anything.”

But she says that’s not the case under SB 100. “You do have power to do something about it. It just needs to be proactive, and we need to do it kind of the right way.”

Nobel Charter Schools: Ending Fees for Discipline - Forever

The word “noble” doesn't appear in SB 100, but one section of the new law was directly inspired by the Noble Network of Charter Schools. It prohibits the use of monetary fines for disciplinary purposes, and it was included in the legislation due to Noble’s track record of charging students fees for trivial offenses.

Lightford first learned of Noble’s fee system when a constituent came to her with a bill for hundreds of dollars in fines, which her son had incurred via minor dress code violations and being late to class. “They were charging students for, if they were late to class or their uniform was inappropriate. … Some of the most ludicrous reasoning that you could hear of receiving a fine,” Lightford says.

With 17 high schools, Noble is the largest charter operator in Chicago. One of those schools is called Rauner College Prep, after Gov. Bruce Rauner, who secured naming rights by donating $1 million to Noble more than a decade ago.

Technically, Noble charged $5 as a “proctoring fee” for detention. Those could rack up rapidly because infractions as small as failure to wear a plain black leather belt could result in four demerits, which trigger an automatic detention. After initially defending the fee scheme, Noble officials dropped it a few years ago. But Lightford wanted it carved in stone. “We wanted to make sure that it was in statute, that it could not happen any longer,” she says.

Given this history, combined with some other districts’ reluctant reactions to SB 100, it’s surprising to hear Cody Rogers say that Noble officials aren’t the slightest bit worried about the new discipline law. Rogers handles media relations for the Noble Network of Charter Schools.

A page from Nobel Charter School Network's student handbook spells out punishments the school could use under Senate Bill 100.

“When SB 100 came along, and we first took a look at it, my understanding is the general feeling was, ‘Oh, well, all right, well this is coming at a good time. We’re taking a look at a lot of this stuff anyway,’” Rogers says. “So it sort of just seamlessly merged with the SB 100 process and kept going. We didn’t have to lose any momentum in what we were trying to develop.”

Noble has a dual reputation for getting its graduates into good colleges but also for imposing a culture of strict discipline. The dress code, for example, goes beyond the standard khakis and school polo shirt. At Noble, kids must wear black (not brown) leather dress shoes. Necklaces must be tucked into their shirts. If a student wears a t-shirt (white only) under his or her Noble polo, the T-shirt sleeves must not hang down longer than the Noble polo shirt sleeves. Dress code violations that cannot be immediately corrected gets the student an automatic 4 demerits and an automatic detention. Demerits are also meted out for being late to class and possession of chewing gum, drinks that aren’t 100 percent juice, chips, Sharpie markers and visible or audible electronic devices.

Those demerits and subsequent detentions carry real weight: Students who accumulate more than 36 detentions are ineligible for promotion to the next grade.

Rogers admits: The rules can look harsh on paper. But he insists these standards come with a large dose of humanity, and that there’s a palpable sense of “joy” in the hallways.

This year, Noble is rolling out a network-wide “freshman amnesty” program that resets detentions to zero after the first quarter. Rogers says the forgiveness program is a retention measure, because without it, Noble was losing too many freshmen, who had hit their maximum detention numbers.

“That sort of works with that idea that as students are adjusting to the Noble professional school environment, there’s going to be some hiccups along the way,” Rogers says. “So we can still enforce those high standards and high expectations and deliver appropriate consequences and hold up the legitimacy of our policy while still realizing that they could use a little help to get through freshman year. And we’re fine in doing that.”

According to Rogers, the only change Noble made for SB 100 was parsing out minimum and maximum penalties in the student handbook. But it still lists potential five-day suspensions for behaviors like forgery, academic dishonesty and possession of tobacco or look-alike products.

How could tobacco warrant a five-day suspension? Rogers suggests a hypothetical scenario of a student bringing tobacco repeatedly or trying to distribute tobacco to other students.

“That’s where context is really important,” Rogers says. “So a student forging a signature on a parent newsletter is way different than a student hacking into our online grade book and changing grades — which definitely, definitely does interrupt the operations of the school, right? Two wildly, wildy different situations and contexts. … If you said there’s only one punishment period for academic forgery and dishonesty, that leaves in our mind way too much wiggle room.”

Recognizing Racial Disparities

Nothing in the new law mentions race or ethnicity, but addressing racial disparities in discipline is one of its goals. Lightford, who sponsored it, has had her eye on the issue since 1999, when six African-American students were expelled for two years from a Decatur high school after a melee at a football game. What concerned her wasn’t that incident as much as the pattern.

Members of VOYCE came to the Statehouse to lobby for passage of Senate Bill 100.

“There was a 2012 study of the federal civil rights data, that found that Illinois suspends proportionately more African-American students than any other state in the entire United States, and had the highest black/white suspension disparity in the country,” Lightford says. “That really solidified for me the urgency to continue working on this and getting something really solid on the books.”

Some educators have read between the lines of the legislation, and recognize that it meshes with their own goals. Adams, the Sullivan High principal who installed a Peace Room, describes the law as “an equity bill that will hopefully … give kids a second chance when they need a chance to right their wrongs, and learn from their mistakes, and will hopefully drop the suspension rates, and the suspension rates of minorities drastically.”

Quentin Anderson helped lead the campaign for SB 100. Anderson, who is African American, worked as a lobbyist for Voices of Youth in Chicago Education (VOYCE). The organization’s young, mostly-minority members have personal experience with the old style of school discipline. Anderson does, too.

At hearings and in lawmakers’ offices, he talked about the record he set when he was in 8th grade for the most office referrals in a single year — a whopping 54 — when five was all it took to get kicked out of his junior high school. For reasons that remain a mystery to Anderson, the assistant principal refused to expel him. With his business suit, lobbyist name tag and law degree, Anderson blended in at the Statehouse when he accompanied VOYCE students there. But his presence at legislative hearings served as a living example of what a “bad” kid could turn out to be.

Quentin Anderson has a law degree and has worked as a lobbyist, advocating for Senate Bill 100. But when he was in 8th grade, he set a record for the number of times he was sent to the principal's office.

Now living in Washington, D.C., he is realistic about whether it’s possible to legislate any kind of nuance into school discipline, when the old mandatory-minimum style had the allure of simplicity.

“If you can just slot people into certain consequences for certain actions, you don’t have to think about what actually happened, because that takes time. And that’s really what our bill tries to do is say that time that seems so inconvenient — that’s really important.

“There’s still ways that people could probably get around it,” he says. “The school districts have lawyers; they’ll figure it out. But what the bill really does is it encourages folks to just look at other ways. If there are other ways available, then look at those first.”

Illinois Issues is in-depth reporting and analysis that takes you beyond the headlines to provide a deeper understanding of our state. Illinois Issues is produced by NPR Illinois in Springfield.