Illinois Issues: The Illinois Constitution at 45

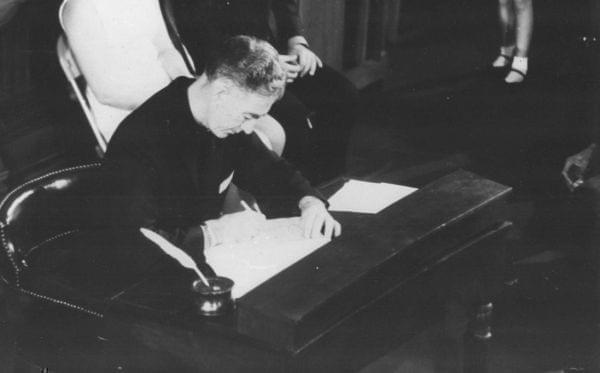

Father Francis X. Lawlor, a an Illinois Constitutional Convention delegate, signs the the new state Constitution in 1970. Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library

Forty-five years ago this month, Illinois voters ratified a new Constitution to replace the state’s century-old predecessor. The framers of the new document saw it as a step into the 20th century for the state from the horse-and-buggy era of the 1870 Constitution.

As Illinois staggers into an unprecedented sixth month without an enacted budget and faces massive bill backlogs and pension debt, now might be an appropriate time to ask how well the 1970 charter has withstood the test of time. Has its promises of streamlined government operations, clear delineations of responsibility and greater ethical behavior been achieved? In retrospect, what obvious mistakes did its authors make? What problems did they overlook or fail to foresee?

As one who covered the Sixth Constitutional Convention as his first major assignment for the Chicago Sun-Times, your columnist admits to a certain bias in favor of the delegates’ handiwork. But on balance, I’d submit the 1970 charter has served Illinoisans well in most regards.

Consider these 1970 updates to the 1870 Constitution.

Making government run more efficiently

With three-fifths votes of the legislature and the governor’s signature, the state can sell bonds to finance major capital improvements like roads and bridges, schools and prisons, mass transit equipment and sewage treatment plants. Currently, the state has authorization to borrow about $49 billion, with roughly $42 billion of general obligation bonds issued, according to a FY 2016 capital plan analysis by the Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, the legislature’s fiscal gurus.

Under the 1870 Constitution, voter approval was needed for the state to borrow more than $250,000, a provision intended to thwart 19th-century boondoggles that led in the 20th century to creation of various quasi-public building authorities to borrow — at higher interest costs — to pay for needed capital projects.

Similarly, the 1870 charter severely restricted the ability of cities and counties to borrow money to finance improvements needed to meet the demands of burgeoning urban populations, resulting in an explosion of independent, special-purpose taxing districts from airports to water service that give Illinois the unwanted distinction of having the most units of local government of any state, presently some 6,000 in all.

In contrast, the 1970 Constitution granted — to cities with populations greater than 25,000 and to anywhere else voters wanted it — home rule, giving them great leeway in managing their internal affairs, including broad borrowing power, intended to reduce the pressure to form special districts. Its provisions for intergovernmental cooperation and special taxing districts within counties and cities also have helped trim almost 500 entities from the 1970 count of local government units.

Clarifying roles of the branches of government

Under the 1870 Constitution, the lieutenant governor served as the presiding officer of the state Senate, following the federal model. So when the Senate — then a 58-member body — was evenly divided between Republicans and Democrats following the 1970 election, Democratic Lt. Gov. Paul Simon effectively gave his party control of the chamber. To protest what he viewed as executive meddling in the legislative branch, the Senate Republican leader, W. Russell Arrington of Evanston, had one GOP senator vote “present” for Senate president.

The Democrats prevailed 29-28, without the need for Simon — a member of the executive branch — to cast a tie-breaking vote in the legislature.

Now, of course, the lieutenant governor has no role in the Senate, which elects its president and other officers from within its own membership.

The 1970 Constitution also created the offices of comptroller and auditor general, each with clearly defined roles. Elected statewide, the comptroller maintains the state’s fiscal accounts and essentially writes the checks to pay for state spending. The auditor general, in contrast, is appointed by the General Assembly and tasked by the Constitution with auditing all the state’s public funds. Having an independent official answerable to the legislature allows lawmakers to be sure public funds are spent the way they intended when they approved the underlying appropriations.

The clear separation between who writes the checks and who audits the books in part came in response to Orville Hodge, who as the popularly-elected auditor of public accounts in the 1950s was able to embezzle more than $6 million in state funds, because his official duties under the 1870 Constitution included both issuing the warrants and doing the post-audit to ensure everything was spent legally.

Promoting more ethical behavior

The 1970 Constitution includes several provisions designed to encourage officials, especially judges, to live up to the public trust. Its Judicial Article, for example, forbids judges from holding other jobs and eliminates fee officers, a class of officials whose salaries depended on money collected from litigants appearing before them.

The document also creates a two-step process for disciplining wayward judges. A judicial inquiry board composed of judges, attorneys, and regular citizens investigates complaints made against judges. The board sends cases deemed meritorious to a courts commission with a similar makeup, which is empowered to impose sanctions up to removal of office for judicial misconduct.

In addition, a general section requires all elected officials and candidates for office to file verified annual statements of economic interests. Delegates added the language — not found in the 1870 document — with a judicial scandal fresh in their minds. A year earlier, two Supreme Court justices came under investigation after the Alton Telegraph disclosed they had secretly accepted stock from a Chicago bank whose general counsel had a criminal case pending before the court. Shortly after the stock changed hands, the high court upheld a circuit court’s dismissal of the criminal charges. In the wake of the resulting investigation, both justices resigned.

Despite best intentions, though, the new ethics provisions have not inspired all public servants to overcome temptation. The long list of latter-day Hodges since 1970 would include a bipartisan lineup topped by two governors, an attorney general, and a state treasurer, followed by a host of congressmen, circuit judges, lawmakers, state bureaucrats, and local officials of all stripes.

Perhaps the most spectacular disappointment has been the 1970 Constitution’s attempt to impose fiscal responsibility.

Unlike its 100-year-old predecessor, the new charter includes a Finance Article that calls for the governor to propose, and the legislature to adopt, a budget in which expenditures proposed by the governor and appropriations made by lawmakers “shall not exceed funds estimated to be available” for the fiscal year.

As this column has noted on previous occasions, the phrasing contains two enormous loopholes, which in the popular mind have allowed governors and lawmakers to regularly pass “unbalanced” budgets.

The loopholes are real enough — “estimated” leaves a lot of wiggle room as budgets are put together and “for the fiscal year” allows bills to pile up from year to year, a la the $6.8 billion backlog Comptroller Leslie Munger reported on November 30. What is often overlooked, though, is that the apparent constitutional mandate applies to all state funds, not just general funds, the state’s checkbook account, which have run in the red since FY 2002. Adding in the 700+ other accounts, the budget usually has shown a surplus, including some $4 billion in FY 14, the most recent year for which data is available from the comptroller.

Other complaints have been lodged, of course. Currently Gov. Bruce Rauner wants lawmakers to send to voters a proposed constitutional amendment that would impose term limits on executive officers and legislators and another that would establish an independent commission to draw new legislative districts every 10 years, rather than allowing legislators to do so.

In fact, more than 1,000 proposed amendments have been introduced in the legislature since 1970, including 64 so far this session. Only 22 have won the necessary three-fifths support in the Senate and in the House to make it to the November ballot. Voters have ratified 12 of those.

The 1970 Constitution also includes a section not found in the 1870 document for a citizens’ initiative, allowing voters to propose limited changes to the Legislative Article. A petition drive now underway would use the provision to revamp redistricting, much as Rauner wishes.

The method has been used successfully only once since 1970, when a last-minute legislative pay raise in the final hours of the 1978 session triggered voter anger that translated into the 1980 Cutback Amendment. Approved by a better than 2-to-1 margin, the amendment sliced the House by one-third and eliminated multi-member districts and cumulative voting, a form of proportional representation that guaranteed both major parties had at least one seat in each of the state’s 59 House districts.

Ironically, the change has been a major factor in the emergence of top-down leadership in the House, best typified by House Speaker Michael Madigan, but now also in vogue with the governor and his mega-millions in potential campaign funds.

Perhaps the best measure of Illinoisans’ satisfaction with their now 45-year-old decision to ratify the current charter comes from another of its innovations, a provision assuring that citizens need not wait another 100 years for a convention.

Instead, the document requires that voters be asked every 20 years whether a new constitutional convention should be called, as a 1968 referendum led to the sixth one. “No,” said three-quarters of the voters — some 2.7 million — in 1988. “No,” repeated two-third of the voters — 3.1 million — in 2008. While support may have slipped over the two-decade span, a convention won’t be called at that rate until the required three-fifths of voters say “yes” in 2088.

The math is fun, of course, and changing events could inspire resounding support for a redraft when the question is next asked in 2028. For now, though, the 1970 Constitution may be showing its age in a few spots, but overall it’s holding up quite well.