Illinois Issues: What Comes Next After ‘No Child Left Behind’?

President Barack Obama signs the Every Student Succeed Act in December 2015 Public Domain

Congress recently authorized a complete rewrite of the unpopular No Child Left Behind Act. What does that mean for Illinois?

If it were possible for all teachers to take two weeks off right now, they’d be floating around the Caribbean on a cruise ship with Congress, sipping pina coladas and indulging in the dinner buffet. That’s because the two groups are enjoying the honeymoon phase of the Every Student Succeeds Act — an extreme makeover of the No Child Left Behind Act.

ESSA, as it’s known, passed on a bipartisan cushion, 359 to 64 in the House and 85 to 12 in the Senate, and was signed into law in December. In broadest terms, the new law hands many decision-making responsibilities back to the states, and de-emphasizes standardized testing.

Small wonder that educators are optimistic that ESSA will free them from the tyranny of bubble tests.

Lizanne DiStefano

“Before, the tests were used very, very heavily to make decisions about how effective schools were, how effective principals were, how effective teachers were,” says Lizanne DeStafano, professor emerita of educational psychology at the University of Illinois. “Under ESSA, that is not the case. So I believe that we’re likely to see much less testing in schools.”

Cinda Klickna, president of the Illinois Education Association, says moving away from such emphasis on testing is a positive development. “What you heard from teachers in the past was that they were teaching to the test, and we think there is so much more than just what a test score shows. What we feel is that this will bring back more of the well-rounded curriculum.”

Diane Rutledge, executive director of the Large Unit District Association, says the administrators in the more than 50 school districts her group represents are “really happy” with what they see so far and “think it’s really going to be much more helpful in the end” for both students and teachers.

“It feels like the federal government is listening to what the concerns have been in the previous law, and in this one, has tried to make accommodations for those,” she says.

Diane Rutledge

Regulations have yet to be promulgated because ESSA is so new. Plus, the fact that ESSA gives states the job of setting standards and devising modes of implementation means that it’s too soon to tell whether this optimism is warranted. A decade from now, these same educators could all be gleefully dusting ESSA off their hands and saying good riddance to it the same way they are to No Child Left Behind. That now maligned act passed by an even bigger bipartisan vote, 384 to 45 in the House and 91 to 8 in the Senate, before George W. Bush signed it into law in 2002.

But NCLB, sometimes shorthanded with the accidentally Dickensian term “Nickleby,” never had a honeymoon phase because it had been a shotgun wedding.

“Among politicians, it was very popular because it was the first thing out of the gate for the Bush administration,” DeStafano says. “It demonstrated that Congress could work together to pass a bipartisan bill, and so I would say that among the federal officials, it was viewed as a great triumph.”

But educators were not celebrating that bipartisan political victory. “Among educational professionals, it was viewed as a tremendous intrusion of the federal government into what had previously been a state and local domain — education — and also starting out with a set of expectations that were unrealistic for teachers and students,” she says. “It was also viewed by many as quite punitive to teachers and school leaders. There was a lot of pressure on them to be evaluated in terms of student outcomes, and a lot of the factors involved in improving those student outcomes were beyond the control of the educators.”

President George W. Bush signs No Child Left Behind in 2002.

Public Domain

NCLB’s over-arching goal was to establish an accountability system for schools receiving federal funds. It required schools to administer standardized tests annually, and prove that an increasing percentage of students passed those tests every year. The goal was for all children to pass the test by 2014. And by “all,” the feds meant even children living in poverty, children struggling with disabilities and children still learning to speak English.

Mike Gudwien has taught English for 22 years at Williamsville High School. It’s a school with a 99 percent graduation rate and consistently above-average test scores, but he says he instantly knew that even Williamsville couldn’t meet that standard.

“When it first passed, I remember talking with teachers and when you get to the full implementation where 100 percent of your student population had to pass the standardized test, it was never going happen at any school,” Gudwien says. “It was just unrealistic, and it didn’t really take into account any of the other issues that impact education, (such as) outside societal influences. It just basically put all the onus on the school to prepare the youth for the future.”

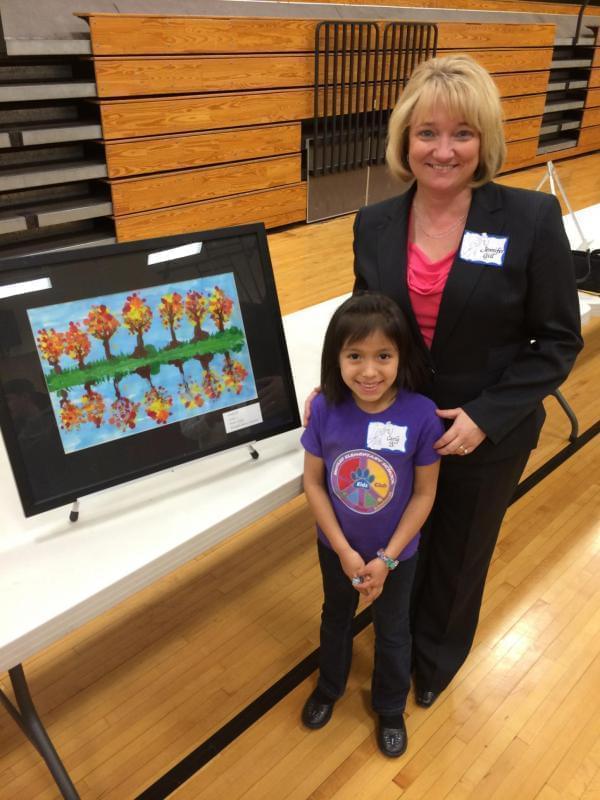

Jennifer Gill with a young student.

Jennifer Gill, now superintendent of Springfield School District 186, was principal at Vachel Lindsay Elementary School when NCLB became law.

“We immediately knew that would be very difficult to attain,” she says. “I think it was the first time we started to see teachers get very frustrated and want to start teaching to the test more than they wanted to just teach the curriculum.”

Schools that didn’t show “adequate yearly progress,” or AYP, were put on probation. If they still failed to improve sufficiently, they were labeled “failing.” That status triggered all sorts of dire consequences. Failing schools had to hire tutors (but only from approved, outside vendors), allow students to transfer to other schools, and create an improvement plan. Schools missing the target for three consecutive years could be forced to “restructure” or even be taken over by the state’s education agency.

At least that was the theory. In reality, the number of schools that couldn’t meet NCLB’s rigid targets was so vast, no state agency could take responsibility for running them all. But that doesn’t mean those “failing” schools didn’t suffer. NCLB required schools to publish test results, along with their assigned label — publicly shaming those schools.

“In terms of how the reporting was and how schools were labeled and, increasingly, how virtually every school in the country was ‘failing,’ I think it stigmatized public education,” Gudwien says. “I think that was the biggest impact it had, in a much larger sense, in how the public perceived public education.”

Rutledge understood why federal authorities thought NCLB was a good idea: They were searching for a way to hold schools accountable, figuring that the specter of being labeled “failing school” would somehow make teachers work even harder. “Looking from their perspective, they had identified those schools as not performing,” she says. “But what we knew was the schools were making progress, and that was the difference. They weren't yet meeting the benchmark, but they were making progress. In No Child Left Behind, you had to either meet the benchmark or not, based upon a test score and not a body of work. And that's how schools got labeled. There was so much negativity in this that good intentions got lost along the way.”

So far, the best thing ESSA seems to have going is that it’s not Nickleby. But what is it?

One thing ESSA does is preserve an element NCLB got right: The disaggregation of test scores by race, gender, language and disability demographics, so that a school’s ability to teach the children who are thriving doesn’t mask its inability to teach children who have some barriers to learning. After all, both ESSA and NCLB are technically reauthorizations of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act — a 1965 initiative passed as part of Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty. The original goal of ESEA was to narrow the academic achievement gap that persists between different demographic groups.

Under ESSA, standardized math and reading tests will still be used annually for grades 3 though 8 and once in high school to monitor how each school is doing. But ESSA, unlike NCLB, won’t rely solely on tests to measure a school’s success. High school graduation rates and English language proficiency will also count toward a school’s ranking, which, under ESSA, will be either “priority, focus or reward,” instead of “failing or “probation.” Each state can choose a fourth factor that might be nothing like a standardized test — advanced coursework, school climate and post-secondary readiness have all been reported as examples.

The National Education Association, a big proponent of this part of the plan, has coined a catchy name for the concept.

IEA President Cinda Klickna

“If you look at the dashboard in your car, and you only focused on your speedometer, and how fast you were driving, but ignored how much gas you had and all the other gauges, you would not really know how your car’s operating,” IEA president Klickna says. “No Child Left Behind focused on that one piece and forgot all these others. What we have been focused on now — and this law will provide — is what we call the ‘opportunity dashboard.’ So what are all the opportunities that a student has in a school to be able to be successful?”

Every factor will be disaggregated by subgroups. And unlike NCLB, ESSA won’t allow “supersubgroups,” a statistical maneuver where a lower-scoring subgroup was combined with a higher-scoring subgroup to achieve better average scores.

ESSA’s de-emphasis on standardized testing includes a provision stating that parents can have their students opt-out, but says each school should achieve 95 percent participation. What happens to schools that don’t meet that target is up to the states. Likewise, states get to determine how to improve under-performing schools. Each state will develop evidence-based interventions to help schools in the bottom 5 percent, schools with a graduation rate below 67 percent and schools where subgroups are struggling.

“The way it looks in this is that the school and the district will always have the first attempt (to remediate problems). If they don’t do well, then it’s up to the state to come in and have a plan in place,” Rutledge says. “What we see in this new bill is the fact that we still have standards, but those can be state-determined. We also have assessments; it will be state-determined. We’ll have accountability; it will be state-determined.”

It’s not hard to see the pattern here.

If it sounds like states are going to have to reinvent the wheel, they’re not. Most, including Illinois, have already done so, through the NCLB waiver program. The federal Department of Education began allowing states to apply for a waiver from NCLB requirements by submitting plans of their own, and all but a handful of states got waivers approved. Aspects of these state plans have shown up in ESSA. For example, one option for testing English Language Learners mirrors Florida’s waiver.

Springfield Title 1 Coordinator Larry McVey

“Illinois hasn’t followed No Child Left Behind now for two and a half years,” says Larry McVey, coordinator of Title 1 programs for Springfield District 186. “Many research articles have said the waiver states are already walking the ESSA line. … So I think it's going to be very much like it has been.”

Another reason Illinois teachers may not feel much difference under ESSA is that —barring a transformation in the General Assembly — the new law’s teacher evaluation guidelines won’t apply here. Unlike the NCLB waiver system, ESSA does not require state teacher evaluation systems to hinge on students’ standardized test scores. But when Illinois applied for a federal Race To The Top grant in 2010, it had to prove that it was ready to implement exactly that kind of evaluation. It did so by enacting the Performance Evaluation Reform Act, which was rolled into a broader Education Reform Act in 2011.

Fred Klonsky, a retired Park Ridge art teacher and education blogger, can’t envision state lawmakers undoing that measure.

“Now that they’ve passed ESSA, that law doesn’t go away,” he says. “Teachers are still going to be evaluated exactly in the way that they were being evaluated before the bill was passed.”

There’s a reason NCLB was passed in the first place: States weren’t doing a great job of educating all children. But after 13 years of NCLB, the federal government hasn’t proven to be much better at it, as it failed to close the achievement gap. And while ESSA basically throws the ball back into the states’ court, it bring in one other player: the private sector.

For example, ESSA contains a provision allowing “pay for success,” also known as “social impact bonds.”

One example of the bonds in action comes from Utah. Goldman Sachs and J.B. Pritzker committed $7 million to fund preschool for some 600 4-year-olds. Tests showed that 110 of those children could be headed for special education, but the investors bet that preschool would cure their deficiencies. When the children reached first grade, only one of those 110 demonstrated a need for special education, according to a story in The Salt Lake Tribune, thereby saving the school district $281,000. The investment bankers received a check for $267,000, which is 95 percent of the savings, and will continue to receive that payout until their $7 million is repaid with interest.

Chicago Public Schools have entered into a $16.9 million social impact bond deal with Goldman Sachs and J.B. Pritzker involving more than 2,600 children.

U.S. Sen. Orin Hatch, a Republican from Utah, took credit for including “pay for success” in ESSA. The provision has been criticized by education experts like Diane Ravitch, Beverly Holden Johns and Mercedes Schneider for injecting a private profit motive into crucial decisions about the education of young children. Johns points out that they are complex contracts where the investors possess the financial expertise. Schneider says these bonds are an “open door for the exploitation” of children who do not score well on tests.

ESSA also includes a provision to help private and religious schools access federal funds, including a block grant program funded at $1.65 billion in fiscal year 2017. States will be required to create an ombudsman position to monitor and enforce distribution of Title 1 and other federal funds to private and religious schools for “equitable services.”

Educators are watching another component of the new law which allows for non-university “teacher preparation academies” run by venture philanthropists to churn out teachers deemed “masters” with little classroom experience.

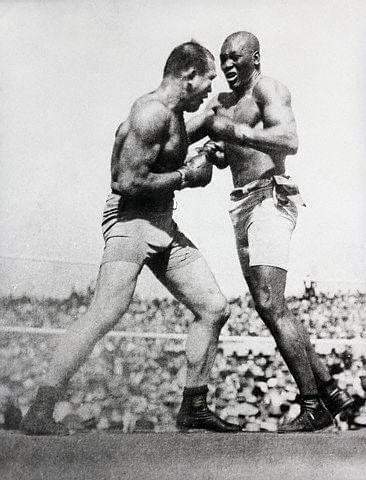

Jack Johnson (right) and James J. Jeffries

Finally, a provision in ESSA that may seem unrelated is the bestowing of a posthumous “sense of the Senate” pardon for Jack Johnson, the first African American heavyweight boxer to win the world title. In 1913, Johnson was convicted of transporting a white female across state lines for the purposes of “prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose,” an act deemed criminal only because of his race. The pardon was inserted into ESSA by a boxing fan, U.S. Sen. John McCain, a Republican from Arizona.

Considering the civil rights legacy of ESSA, NCLB and ESEA, perhaps the provision is fitting after all.

Illinois Issues is in-depth reporting and analysis that takes you beyond the headlines to provide a deeper understanding of our state. Illinois Issues is produced by NPR Illinois in Springfield.