Illinois Issues: What’s Up With The Judicial ‘Smackdown’ Of Remap Referendums?

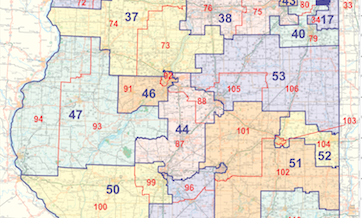

A portion of a map showing Illinois' legislative districts for the state House & Senate. Illinois State Board of Elections

Commentary - Can Illinois voters change by referendum the constitutional provisions for drawing new legislative boundaries? Not under the Democratic justices’ rigid reading of the state’s constitution, say the three Republican justices of the Illinois Supreme Court.

Certainly, as long as they stick to the narrow terms of the charter’s voter initiative provision, say their four Democratic counterparts on the high court.

The stark difference of opinion highlighted the court’s recent decision that kept from the November ballot a citizen initiative to take redistricting away from the legislature and place the responsibility in the hands of an independent commission.

Almost 564,000 voters signed petitions backing the referendum on the proposed amendment, but by a 4 to 3, party-line vote, the court’s Democrats ruled that the proposal went beyond the structural and procedural changes the Constitution permits by creating a new role for the state auditor general in the remap process.

While redistricting is a valid subject for initiative, Justice Thomas Kilbride wrote for the majority, the current proposal “is not the only model of redistricting reform that could be imagined.” Citizens’ constitutional right to alter the legislative article by ballot initiative “is not tied to any particular plan, and we trust the confines [of the article on constitutional revision] are sufficiently broad to encompass more than one potential redistricting scheme.” The ruling echoed the conclusion reached in earlier cases by two Cook County Circuit Court judges.

The Supreme Court decision triggered howls of protest from hyperventilating editorial writers and columnists, including suggestions from the usual suspects that House Speaker Michael Madigan was behind it all.

Included in the negative response was a notably strident dissent from Justice Robert Thomas, couched in stronger terms than the usual judicial pronouncement.

“The Illinois Constitution is meant to prevent tyranny, not to enshrine it,” the justice wrote. “Today... four members of our court have delivered, as a fait accompli, nothing less than the nullification of a critical component of the Illinois Constitution of 1970... the majority has irrevocably severed a vital lifeline created by the drafters for the express purpose of enabling later generations of Illinoisans to use their sovereign authority as a check against self-interest by the legislature.”

The majority opinion was “a death knell” of the charter’s promise of direct democracy as a check on legislative self-interest, Thomas added.

“Today a muzzle has been placed on the people of this State, and their voices supplanted with a judicial fiat,” he wrote. “The whimper you hear is democracy stifled. I join that muted chorus of dissent.”

In the lead dissent, Justice Lloyd Karmeier rejected in more scholarly language every challenge brought by the initiative’s foes, concluding that under the majority’s reading of the initiative provision, “the promise of any real change to the present redistricting system would be rendered illusory.”

The majority’s observation that the initiative provision was sufficiently broad to encompass various redistricting plans “is unquestionably true,” Karmeier noted. “The confines are broad enough to include a range of possible systems for carrying out redistricting. The problem is that under the contorted and restrictive approach urged by the majority, none of these potential redistricting schemes could possibly pass constitutional muster.”

At the heart of the controversy was a proposal, advanced by a bipartisan coalition called Support Independent Maps, that would create an 11-member, independent panel to draw new district lines every 10 years following the federal census. Members would be chosen through a two-step process. Both steps would involve the auditor general, which was the plan’s most significant legal flaw, in the eyes of the high court majority.

A group called People’s Map headed by minority and ethnic business leaders sued to block the plan, alleging its provisions exceeded what the Constitution allows in half a dozen ways, all involving changes that were not “limited to structural and procedural subjects” contained in the charter’s Article IV — The Legislature, as required.

Agreeing with People’s Map on each point, Cook County Circuit Judge Diane Joan Larsen held the proposal unconstitutional. But she also noted, “After weighing the relative merits of the parties’ arguments, the court finds that redistricting in general is a structural and procedural subject... and that the Redistricting Initiative at issue addresses a structural and procedural subject.” The problem, she wrote, is that the initiative was not limited to those subjects, as the Constitution requires, but instead brought in other issues.

Her conclusion echoed the opinion issued by Cook County Circuit Court Judge Mary Mikva last year in a similar case involving a petition drive to change redistricting. Mikva ruled the proposal was fatally flawed, among other things because its ban on panel members running for office later improperly changed the eligibility requirements for those offices.

However, Mikva wrote that redistricting itself “appears to be fair game” for an initiative. “A differently drafted redistricting initiative could be valid,” she wrote, but the proposal before her was not.

For those keeping score at home, both a majority of the Supreme Court and the two trial judges who’ve heard related cases believe changing how districts are drawn is a valid subject for voter action, as long as the proposals don’t affect other constitutional provisions.

The Supreme Court minority and assorted pundits say the gate envisioned by the majority in reality is too narrow for any petition drive to traverse.

So whose take might be correct?

Some insights might be gathered by reviewing the discussions the framers of the new constitution had about permitting citizen-proposed amendments in the new charter they were drafting.

For starters, whether to permit amendments via the citizen initiative was not a major topic at the Sixth Illinois Constitutional Convention. Delegates were focused more on controversial issues, such as whether judges should be elected or appointed, whether cities should be given home rule powers and whether House districts should continue to have three members, elected by a process called cumulative voting. A new revenue article and hot-button issues like the death penalty and the voting age also demanded much attention.

The committee reviewing procedures for amending the constitutional was first to consider the question of citizen initiative. The panel voted 5 to 4 to omit the initiative plan from its rewrite of the 1870 constitution’s amendment article. The majority believed that other changes they proposed — notably reducing the votes needed for lawmakers to propose and for citizens to ratify amendments, along with an automatic convention call every 20 years — would afford sufficient opportunity for constitutional changes as needed in coming years.

Instead, the initiative was offered as a minority report, in a form that would have permitted changes to any part of the constitution. Delegates found that power too broad.

Typical was the concern voiced by David Davis of Bloomington, a retired lawmaker who had served more than a decade in the Illinois Senate.

“I can’t help wondering what would happen tomorrow if someone started circulating three petitions for constitutional amendment — one to eliminate the income tax, another to eliminate the personal property tax, and a third perhaps to eliminate the sales tax,” Davis asked. “Do you really think it would be very difficult... to get the signatures necessary for the petition or to get the votes necessary for the passage of the adoption of such a constitutional amendment in either of these three cases? And if that sort of thing can be produced by the initiative method... isn’t this a very dangerous situation to create?”

After a relatively brief debate, by Con-Con standards, delegates rejected the initiative, 60 to 44. Those voting against the plan included the two Chicago Democratic incumbent lawmakers serving as delegates, Chicago Democratic Reps. Victor Arrigo and Paul Elward, and two other young Chicagoans just embarking on political careers, Richard M. Daley and Michael J. Madigan.

Later in the convention, a scaled-back version resurfaced, crafted by the committee working on the legislative article. The new plan restricted voter-initiated changes to structural and procedural subjects in the legislative article, “the area of government where it probably would be most needed because of the vested interest of the legislature in its own makeup,” explained Louis Perona of Spring Valley*

, who presented the plan to delegates. Moreover, the limitations “have cleared up in many delegates’ minds the problems and objections they had” with the original proposal opening the door to wholesale rewrites.

Peter Tomei of Chicago asked what the language would allow. “You refer to structure, size, et cetera; and under the pertinent sections of this proposed article, the first grouping of them — power, structure, composition, and apportionment — you do deal with size and with elections. You deal with cumulative voting — matters of that nature — and is that the kind of thing, also, that would be subject to initiative under this proposed section 15?”

“Yes,” replied Perona. “Those are the critical areas, actually.”

Delegates narrowly endorsed the committee plan by a show of hands 51 to 47, without a formal roll call, and later voted 78 to 26 for its inclusion in the final draft of the new charter.

So clearly redistricting is, as Mikva said, “fair game;” the challenge for those advocating for a new procedure would seem to be to follow the guidance provided in the court opinions.

The Independent Maps coalition has asked the Supreme Court to reconsider its decision. The group says it hopes the court will come to a different conclusion. But if it doesn’t, they say they want more guidance from the justices on how to draft an amendment that would be acceptable.

In case that guidance doesn’t come, here are some broad suggestions:

1: At a minimum, don’t include anything that could be construed as extraneous. No new duties for the auditor general — an office created by a different article of the constitution.

2: No limits on future office seeking by those drawing the maps.

3: Don’t tinker with the Supreme Court’s exclusive jurisdiction on remap cases, nor with the attorney general’s charge to initiate legal action in the people’s name, both issues included in the most recent failed plan.

4: Keep the independent commission, but find someone else to screen the applicants, somebody not mentioned elsewhere in the Constitution. Perhaps a legislative support body, like the Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, or the office of the Legislative Inspector General. Maybe a private entity, like the Illinois State Bar Association, or a group of academics specializing in demographics, GPS tools, information systems or other related fields.

Sure, making another run at an amendment would be huge undertaking, especially in the wake of successive judicial smackdowns, as one newspaper put it. But paying for a new drive shouldn’t be an issue, considering the record amounts of cash being dumped into a relative handful of legislative races, none of which would have anywhere near the impact that changing the remap process would. Voter enthusiasm likely remains high, so getting a new round of signatures probably is more a matter of dogged determination than clever advertising.

In the best of all worlds, of course, the legislature’s majority Democrats themselves would approve an amendment for the 2018 ballot, thus undercutting what’s emerged as a key Republican campaign issue. But don’t hold your breath.

Charles N. Wheeler III is director of the Public Affairs Reporting program at the University of Illinois Springfield, and covered the Sixth Illinois Constitutional Convention for theChicago Sun-Times.

Illinois Issues is in-depth reporting and analysis that takes you beyond the headlines to provide a deeper understanding of our state. Illinois Issues is produced by NPR Illinois in Springfield.

* A previous version of this story stated that Louis Perona was from Wilmington.

Links

- Former Gov. Quinn Unveils His Own Redistricting Reform Plan

- Illinois Redistricting Referendum Won’t Appear On Ballot

- Judge Blocks Illinois Redistricting Plan From Ballot

- Redistricting Initiative Takes Next Step Toward November Ballot

- Group Trying Again To Reform Redistricting

- Madigan: “Campaign Purposes” Behind Rauner’s Term Limits, Redistricting Push