Red Summer In Chicago: 100 Years After The Race Riots

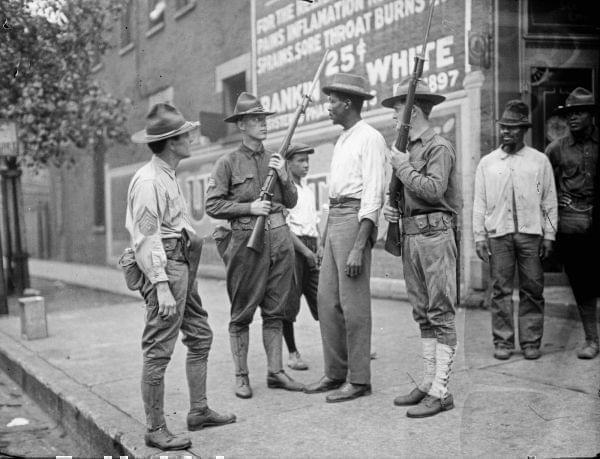

Armed National Guards and African American men standing on a sidewalk during the race riots in Chicago, Illinois, 1919. Jun Fujita/Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum

Exactly 100 years ago today, Chicago was in the throes of a brutal heat wave. Thousands flocked to the beaches lining Lake Michigan for some relief. Among them: a group of black boys that included 17-year-old Eugene Williams. Eugene, who was on a raft, inadvertently drifted over the invisible line that separated the black and white sections of the 29th St Beach. One white beachgoer, insulted, began throwing rocks at the black kids. Eugene Williams slipped off his raft and drowned.

That incident ignited a race riot that would go down in history as one of the country's bloodiest, and least-known, to date.

And Chicago wasn't the only place this happened. What would come to be referred to as the country's Red Summer was a series of race riots that occurred for several months in different places around the country. In Chicago, Eugene Williams' death was what sparked the city's riots, but kindling for that fire had been building for at least a few years.

For one thing, the city's demographics were changing very quickly. 100-year-old Timuel Black Jr. is a historian, educator and activist who has lived most of his long life in Chicago. He came to the city with his parents as an infant a few months after the riot, but stories from relatives and neighbors made it very clear why so many black folks were streaming into Chicago.

People, Black said, "wanted to move forward and break the barriers of segregation." According to Black, three major factors were propelling black Southerners forward: "to escape the tyranny and violence of the Ku Klux Klan, to be able to vote without fear and to get better education for their children," he says.

So many newcomers at once strained the city's resources. "At the time, people in Northern cities—especially Chicago—saw it as an invasion," says John Russick of the Chicago History Museum.

The South Side neighborhoods to which black Chicagoans had been traditionally relegated were bursting at the seams. There was fierce competition for the existing apartments and homes, even though many of them were substandard.

Adding to the tension: soldiers were returning home after serving in Europe during World War I. Black soldiers, in particular, had experienced being treated as complete citizens while they fought abroad. Returning to an America that barely recognized their service and wanted them back in their assigned, segregated places was not something they were willing to accept.

Adding to the tension was fierce competition over jobs. The black newcomers readily accepted jobs in the city's slaughterhouses and meatpacking companies because the pay was better than what they'd received in the South. That outraged the European immigrants—Irish, Italian, Czech and Polish—who'd traditionally held those jobs and who wanted to unionize the companies they'd worked for.

So pressure was building, and Eugene Williams' tragic death at the beach was the final straw. Liesl Olson is director of the Chicago History project at the Newberry Library, and says, to add insult to the injury of Eugene's death, "a white policeman refused to arrest the white man who'd caused an African American teenaged boy's death."

The police's inaction doesn't surprise John Russick. "The white police were a tool of white supremacy in Chicago at this time," he explains. "All of the tools of power were in the hands of white people in 1919, and we can't lose sight of that."

Anger escalated on the black side of the beach when it became apparent that no arrest would be made. More police arrived. One especially distraught black beachgoer pulled out a gun and fired into a knot of police. He was shot dead immediately.

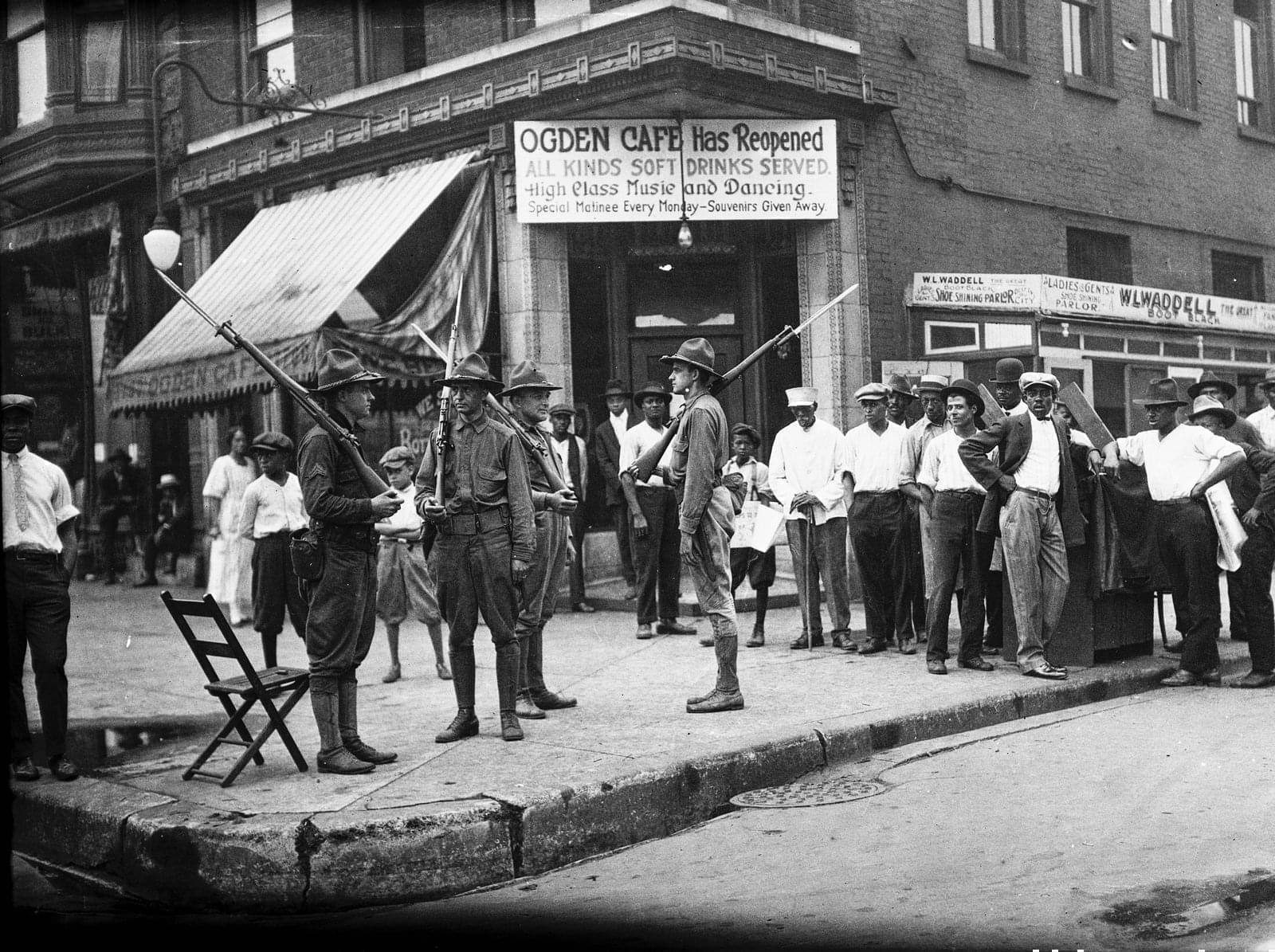

A group of men and armed National Guard in front of the Ogden Cafe during the race riots in Chicago, Illinois, 1919.

The tale of Eugene's death and the shooting that followed angered groups of young white men. Some climbed into cars and began racing through major streets in the city's black neighborhoods, randomly firing at homes and businesses. Others armed themselves with guns, sticks and rocks and began marching up 35th street, assaulting any black person unfortunate enough to cross their path.

Juanita Mitchell had just come to Chicago with her family. They were staying with relatives until they found their own place. Mrs. Mitchell is 107 now, but still clearly recalls her terror as the eight-year-old girl she was then.

"I remember how afraid my mother was, how afraid my aunt was," she says. "I remember my uncle standing in the window and I heard him say 'here they come'—which meant the race riot was coming down 35th and Giles."

Her uncle was armed "with the biggest gun I had ever seen," Mitchell recalls. He was prepared to protect his family. So were many of the returning black veterans. A group of National Guard reserve men who'd returned from France after fighting valiantly there, broke into an armory and grabbed guns and other weapons, determined to protect black lives and property.

That resistance was a watershed, says Timuel Black Jr. "I understand that this was the first time these Northern Negroes fought back from an attack and been successful."

So successful, in fact, that the riot soon wound down.

"From what I've been told by my family who was here, the riot was soon over, because the Westside rioters felt they were in danger, now that these Negroes returning from the war had weapons equal to their weapons."

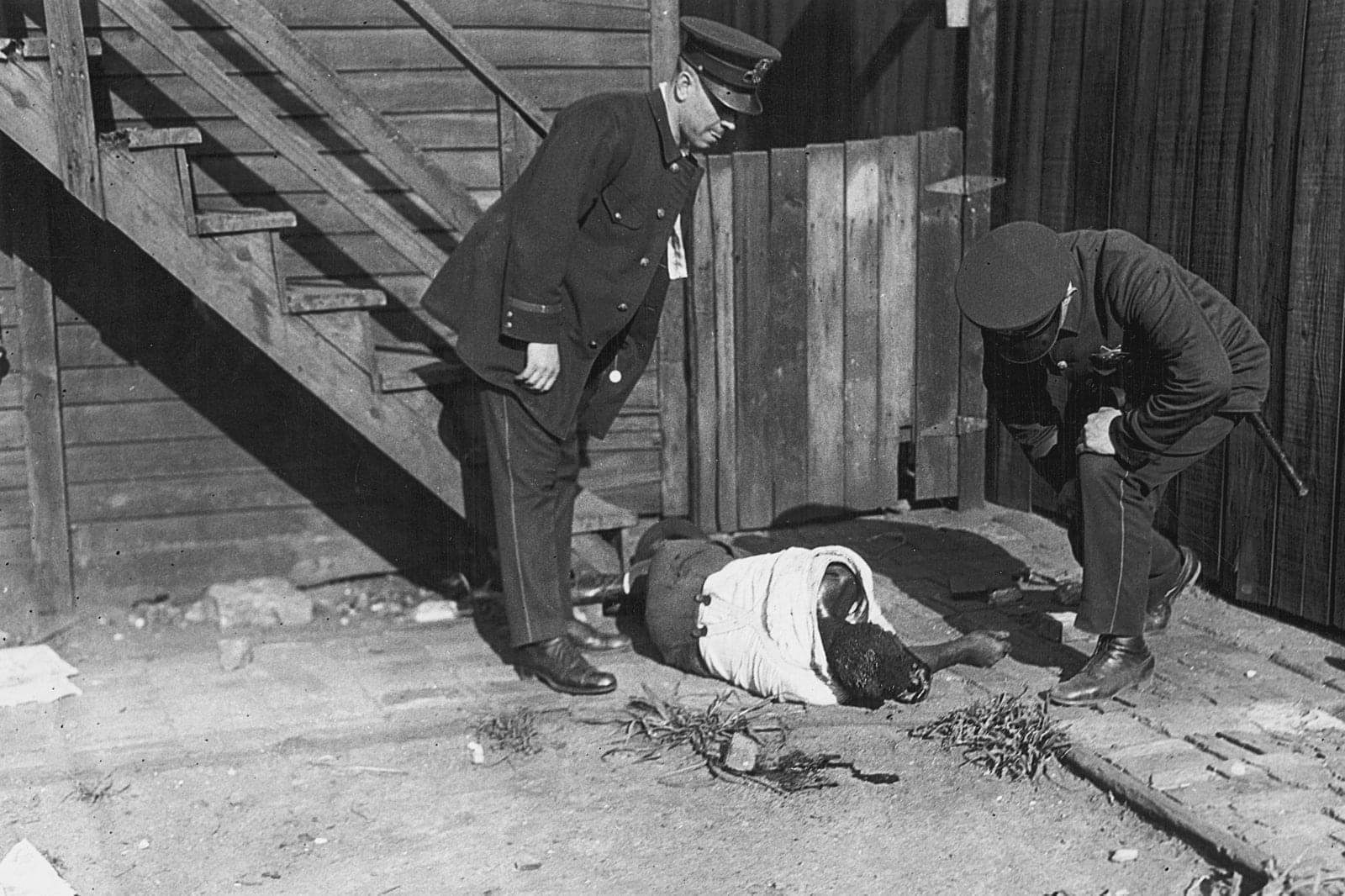

When the smoke cleared and the ashes cooled, 38 people—23 black, 15 white—were dead. More than 350 people reported injuries.

African American victim of race riot stoning lying on ground, with police standing above, Chicago, Illinois, 1919.

And it wasn't just Chicago: more than two dozen cities throughout the country had their own Red Summers—in Washington DC, Houston and Charleston all experienced racial violence. In Elaine, Arkansas, some 200 people were presumed dead.

"The struggle over jobs, the return of black soldiers from the war and not being treated with respect and not finding employment - those tensions were in so many places," says Liesl Olson.

In Chicago, some 1,000 black homes had been burned down. None of the white participants in the riot ever faced consequences for their involvement.

"It shouldn't be a surprise to anyone, looking back 100 years later, that the response to the violence perpetrated upon African Americans in the wake of the incident at the beach wasn't aggressively prosecuted or even investigated after the fact," says John Russick.

And although that was true in the immediate aftermath, a commission, established by the governor, released a report three years later: The Negro In Chicago: A Study on Race Relations and a Race Riot. The commission members, six black men, six white men, looked at the root causes behind the riot and concluded, as would the Kerner Commission Report 50 years later, that racial inequality was a major reason for the violence.

Row of armed National Guard sitting in front of a storefront during the race riots in Chicago, Illinois, 1919.

That was then. What about now? Is the Red Summer relevant to us today?

John Russick thinks so. "We think these things can't happen again," he says. "We think of the past being past, but at this moment, the race riots are with us still. We're still struggling with how to get along with each other."

Eve Ewing teaches at the University of Chicago and has just published a new book, 1919, which retells the cataclysmic events of the Red Summer through poems. Past, says Ewing, is, sadly, prologue.

"What does it mean to have the story of Eugene Williams, 17 year-old black boy, which then becomes the story of Emmett Till, which ten becomes the story of Laquan McDonald?" she asks. "What does it mean for us to be constantly living this recurring nightmare?"

Chicagoans have been examining just that all year long, in an effort to better understand Red Summer. This weekend, there will be services, lectures, even a walking tour of some Red Summer sites, in an effort to learn from--and not repeat--this chapter of the city's history.