The Professor Who Made Movies Talk

Joseph Tykociner, University of Illinois professor of electrical engineering, stands with all of the equipment used to create sound motions pictures in the world's first successful demonstration of sound on film on June 9, 1922. This demonstration was in the Physics Lecture Room. Courtesy of the University of Illinois Archives

For many film buffs, the movies’ transition from a silent medium to one with sound is marked by Al Jolson performing in the 1927 movie, “the Jazz Singer”. But the beginning of sound in the movies could also be marked by the test films made in 1921 and 1922 by a University of Illinois professor, Joseph Tykociner.

Wednesday, October 5th, marks the anniversary of Tykociner’s birth in 1877. He was one of the pioneers in the development of optical sound recording, a method that remained the common format for motion picture sound until Thomas Edison's invention was overtaken by digital technology. But despite his early accomplishment with the technology, Tykociner remains on the sidelines of film history.

One reasons may be that while “The Jazz Singer” is a vibrant example of Hollywood filmmaking, Tykociner’s experiments in sound film were exactly that --- experiments. The earliest example of his work isn’t a motion picture at all, but a strip of movie film with a sound track but no picture. Played back today, one can hear (over heavy background noise), the voice of Joseph Tykociner testing his apparatus with the words, “This is an experiment in the reproduction of sound.” He then proceeds to count to ten, and concludes his test with a loud “Halloo!”

First Inspiration

At the time of the recording, Tykociner was a University of Illinois assistant professor, the university’s first in the field of electrical engineering. He was a few months away from demonstrating his sound-on-film motion picture technology in a public setting. That demonstration would come a full five years before “The Jazz Singer,” which didn’t record its sound on film at all. That’s a detail that Tykociner would explain in an interview, forty years later.

“That was not at all sound on film, the how-do-you-call it, 'The Jazz Singer,' you know,” said Tykociner in 1967. “That was not a sound picture. That was just records, a box with records. And tremendously expensive, I understand they spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to develop that.”

Tykociner was correct. “The Jazz Singer” used the Warner Brothers Vitaphone technology developed by Western Electric, which synchronized a movie with a soundtrack recorded on phonograph records.

Tykociner had publicly demonstrated his method of optically-recorded sound movies at the University of Illinois on June 9, 1922. But the idea had come to him a quarter century earlier, as a teen-ager in his native Poland. The young Tykociner had been fascinated by the phonograph, but wanted better sound quality, akin to what he heard on the telephone.

Then, in 1896, he made his first visit to America. Looking back from 1967, Tykociner remembered walking down Manhattan’s Broadway, entering a storefront movie theater and seeing his first motion pictures. They were shown on a “Bioscope,” an early rival to Thomas Edison’s motion pictures, using work-around patents awarded to a former Edison employee. Tykociner’s conclusion about the movies was that like the phonograph, they could use some improvement.

“A band was marching along, a steamer announced its coming by whistle”, said Tykociner of the movie images he saw on the screen. “But there was no sound at all. The only sound was the ticking of the machine. And I thought, now, they have invented moving pictures, but where is the sound? And that’s the moment when I got the idea, that now, we can photograph together, with the picture, the sound itself.”

Tykociner returned to Europe to finish his studies. He became an electrical engineer specializing in the new field of wireless telegraphy -- better known today as radio. But off and on, on his own time, he worked on the idea of recording sound on motion picture film.

Tykociner was in his forties when he returned to America, and joined the faculty of the University of Illinois, which gave him the backing to make his idea for sound-on-film motion pictures a reality.

Joseph Tykociner, University of Illinois professor of electrical engineering, stands with all of the equipment used to create sound motions pictures in the world's first successful demonstration of sound on film on June 9, 1922. This demonstration was in the Physics Lecture Room.

First Public Demonstration

His first public demonstration of the new technology was given in the lecture room of what was then the Physics building at the University of Illinois Urbana campus. Those in attendance saw harshly lit pictures of people ringing bells, reciting oratory and playing the violin. The subjects stayed close to the microphone -- one that had been taken from a telephone mouthpiece, with a megaphone attached to capture the sound. The film’s sound track was plainly visible on the right-hand side of the movie image, a strip that carried the encoded sound by shifting quickly from white to shades of grey and back again.

When the film is played back today, the sound quality is a few steps below that of “The Jazz Singer,” with limited fidelity and a high level of background noise. But Joseph Tykociner had successfully demonstrated a new way of recording sound -- an optical recording method based on the modulation of light patterns -- that could be paired with motion pictures. He was eager to improve it, and looked to the university for additional backing.

Dispute Over Ownership

But here, his troubles began. University of Illinois policy discouraged work on inventors’ personal projects that would benefit them financially. That ran counter to Tykociner’s proposal that he keep control of his invention, while giving the university a share of future revenue in exchange for funding further research.

Four months after the demonstration, University President Joseph Kinley told Tykociner in a letter that such an arrangement would be improper.

“We shall have to ask you, if you decide to continue working with us, to devote yourselves to some other problems which shall not have the appearance of promoting the investigation whose commercial development is of so much personal interest to you,” wrote Kinley in his letter.

Nowadays, universities encourage commercial development of their faculty’s research. It’s called “Technology Transfer,” but that term was unknown in the 1920s. Tykociner considered surrendering the rights to his invention to the university, so that the perceived conflict of interest would no longer be a problem. But he couldn’t be sure that the university would let him continue research on sound-on-film movies, even under those circumstances.

In his letter, President Kinley told Tykociner that if developing his sound motion picture device was so important to him, he should take his invention to a private firm like General Electric, which was already doing work in the field. Kinley insisted that he did not want to lose Tykociner, but that he would have to surrender control of his sound-on-film movie process to the university if there was to be any further research on it. Tykociner considered that option, but feared that he even if he did so, he would not be allowed to do further work on his invention.

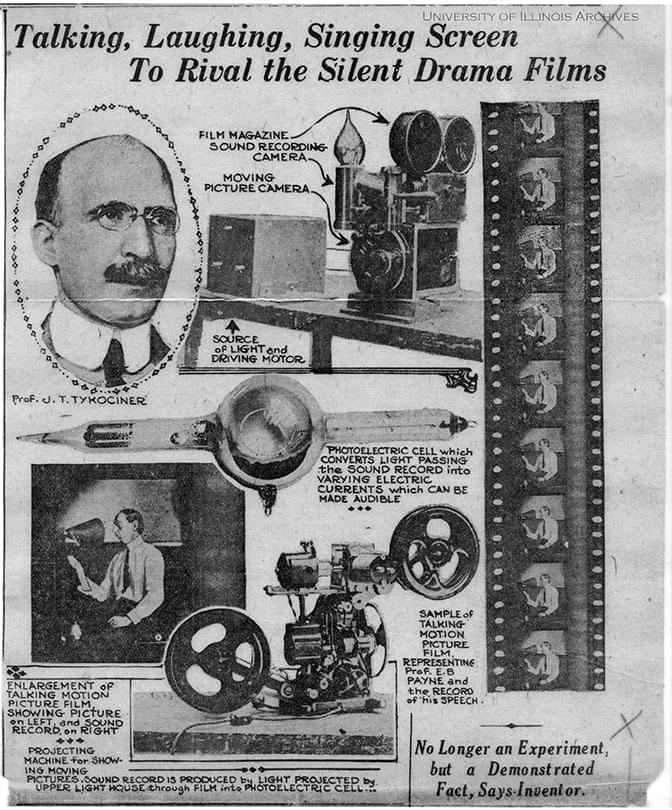

News clipping from The New York World explaining the process created by University of Illinois professor of electrical engineering Joseph Tykociner to put sound on film from July 30, 1922

Tykociner considered going out on his own, and made contact with General Electric and other companies. He also hired an attorney to see if he could attract enough investors to fund his own research. And once his invention was patented, he tried to license them with movie equipment manufacturers.

But Tykociner was no entrepreneur. For him, the business side of movie technology, with the constant calls for information and demonstrations was an irritating distraction. And he could never come to terms on money with his potential business partners or employers.

He wasn’t really geared up to be the next Thomas Edison.” Donald Crafton

In the view of film historian Donald Crafton, Joseph Tykociner was at heart a researcher, not a businessman.

“He wasn’t really geared up to be the next Thomas Edison,” said the Notre Dame Film Studies professor, whose 600-page book, “The Talkies: American Cinema’s Transition to Sound 1926-1931,” devotes just a paragraph to Tykociner. Crafton devotes far more space in his book to Tykociner’s rivals, the people and companies who were working on their own versions of optical sound recording. Tykociner did not learn that he had rivals until he was nearly done with his prototype at the University of Illinois.

“In the 1920s, it was the era of big business and corporate capitalism,” said Crafton. “And you had to be a corporation, not an individual, to really succeed and monopolize the market.”

Two corporations, RCA and AT&T’s Western Electric (which had hedged its bets with the sound-on-disc Vitaphone technology) would end up dominating the market for sound movie technology in America.

In 1927, Tykociner sold his sound-on-film patent for $50,000, according to film historian Scott Eyman, in his book, "The Speed of Sound", which devotes two paragraphs to the researcher. Eyman's book does not identify the buyer, or how Tykociner's patent was used.

A Prophet With Honor In His Own Land

Meanwhile, Joseph Tykociner would stay at the University of Illinois, and away from any further work on sound motion pictures. The work he had already done was largely forgotten -- except at the U of I. There, Tykociner would always be presented as the first and greatest inventor of sound-on-film motion pictures.

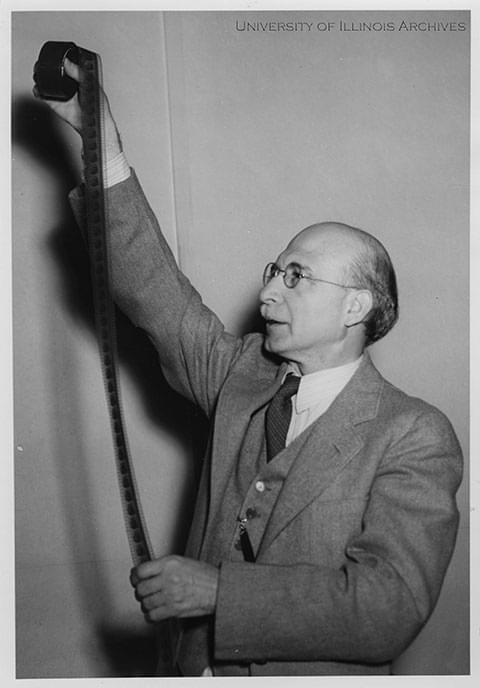

Joseph Tykociner, developer of the first technique to put sound on film, looks at a reel of film in a 1949 photo.

Courtesy of the University of Illinois Archives

For example, a 1949 radio documentary produced at the university by WILL Radio, outlined a simple trajectory, from the days of silent movies, to Tykociner’s invention, to “The Jazz Singer,” and then to modern sound movies.

“Remember the days of the silent flickers, when the tinny piano was the only sound that accompanied the thrills of the screen?” asked the program’s announcer, as old-time silent movie music played in the background. “You know, that might still be the case, if it hadn’t been for one man.”

The documentary (which can be heard in the audio file above) doesn’t mention the frustration Tykociner felt about giving up his research on sound for the movies. And in later years, absorbed in other pursuits, he didn’t talk about it much.

But Tykociner had outlined those frustrations succinctly in a 1923 letter to a relative, as “years of efforts, complete attainment of the object in view, short moments of satisfaction and appreciation, a flood of correspondence and finally full disappointment.“

This article is based on materials in the Joseph Tykociner Papers, in the collection of the University of Illinois Archives. Thanks are due to Bethany Anderson and the rest of the Archives staff for their help in providing access to the Tykociner Papers.

UPDATE: This article has been updated to include links to a newer, digital restoration of Joseph Tykociner's sound-on-film demonstration reel, and to note Scott Eyman's report that Tykociner sold his patenyt rights in 1927. - JM 10/4/19, 10/6/2020.