Weeding Out Competition: Farmers Left Paying Steep Prices As Seed Firms Merge

A central Illinois farmer harvests corn toward the end of the 2016 harvest season. As of Oct. 25, the price of corn was about $3.50 per bushel. Darrell Hoemann/Big-AgWatch.org

Central Illinois corn and soybean farmer Norbert Brauer said he remembers when he could plant an acre of corn for about $100 total.

But that was nearly three decades ago. In 1990, the $100 cost covered “everything,” he said, including fertilizer, pesticide and — most importantly — the corn seed itself.

This planting season, Brauer paid more than $100 an acre for corn seed alone.

University of Illinois researchers found that seed corn prices averaged $23 per acre in 1990 and $118 per acre in 2015. The bundle of direct costs involved with growing an acre of corn in 2015 topped $400 per acre.

“The seed cost has gone up tremendously,” said Brauer, who also serves as president of the Illinois Farmers Union. “The reason for that is concentration in the seed business.”

Seed companies sell varieties of seeds with traits that help farmers withstand drought or ward of crop-destroying pests such as weeds and insects. To create those traits, companies use a mix of traditional breeding methods and genetic engineering techniques. Seeds produced with genetic engineering are commonly known as genetically modified organisms, or GMOs.

Agribusiness powerhouses have gobbled up hundreds of small-scale seed companies since 1990, research from Texas A&M University’s Agricultural and Food Policy Center reveals. Those buyouts have left just a few dozen independent sellers remaining. The vast majority of the corn seed market is dominated by four companies: Monsanto, DuPont, Dow Chemical and Syngenta AG. The same four companies control most of the soybean seed market as well.

Combined, they netted more than $102 billion in 2015 sales, financial reports show.

Critics believe the acute concentration of seed companies has generated an uncompetitive market that has hurt farmers by raising the price of seeds as commodity prices have dropped. Farmer profit is so weak that the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced in early October that it plans to pay more than $7 billion in taxpayer money to keep growers in business.

Seed costs have increased faster than fertilizer, pesticide or any other input cost, according to the Texas A&M University research. In recent years, seed prices have skyrocketed by as much as 30 percent annually.

Tamara Nelsen, senior director of commodities the at Illinois Farm Bureau, in her office with a variety of seed bags from the past. Photo on Oct. 5, 2016.

“Prices for seed and the cost of seed as a percentage of a farmer’s total cost have gone up significantly,” said Tamara Nelsen, senior director of commodities at the Illinois Farm Bureau. “It’s been really rapid change, and even I can’t remember all of the names of the companies who have merged or acquired each other since the old days of multiple seed companies in every area that farmers could buy from.”

And now the number of players in the seed industry is poised to shrink even further.

The most powerful agribusiness companies began pairing up in December when Dow Chemical and DuPont announced they were merging in a $130 billion agreement. A month later, the government-owned China National Chemical Corporation bought the Swiss biotechnology firm Syngenta AG for $43 billion. The deal is the largest-ever foreign takeover by a Chinese firm.

In September, German pharmaceuticals maker Bayer entered into a $66 billion all-cash deal to buy St. Louis-based Monsanto, the world’s top seed company.

“Reduced competition,” Nelsen said. “I think that’s always the first reaction from folks when you hear of not just one merger, but another and then another.”

The three pending merger agreements — which transform agriculture’s “Big Six” into the “Big Four” — are valued at a combined $239 billion. But each deal still needs to be reviewed by U.S. antitrust regulators and their international counterparts. If regulators believe the mergers would likely lead to diminished competition and monopoly-like advantages, the deals could be stopped or face strict break-up requirements.

“The idea with merger laws is we don’t wait until [a competition] problem is fully formed,” said Spencer Waller, a professor at Loyola University Chicago’s School of Law and the director of the Institute for Consumer Antitrust Studies. “We stop deals if we think they will contribute to creating a monopoly down the road.”

The U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee held a hearing in September to investigate how consolidation in the seed and agrochemicals sectors would affect America’s farmers. The Justice Department has also reached out to farm groups to hear their take on the mergers.

Brauer — like many Corn Belt farmers — said the scrutiny comes too little too late.

“The consolidation has already happened, and if we were going to have hearings on it, then that should have been years ago,” Brauer said. “That’s when the competition got weeded out.”

Outside the DuPont Pioneer research center in Champaign, Ill.

Photo Credit: Darrell Hoemann/Big-AgWatch.org

Corn, soybean seed costs expected to increase slightly

The seed industry has experienced at least two previous periods marked by acquisition frenzy.

Most American farmers saved seed from their crops and often shared them with neighbors until the late 19th century, according to the USDA. Very few bought seed from commercial sources. That changed around 1915, when farmers turned to traders who offered quality assurances. Dozens of new seed sellers eventually opened shop, and by 1944, U.S. sales in corn seed grossed $70 million.

The first wave of major consolidation happened in the 1970s, when the market noticeably shifted toward large companies. More than 50 seed companies were acquired by pharmaceutical, petrochemical and food firms during that time. The trend continued into the early 1980s, when the rise of biotechnology paved the way for attractive investment opportunities.

Monsanto headed a second wave of consolidation that kicked off in the 1990s. It acquired nearly 40 plant biotechnology businesses including Agracetus, Calgene, Holden’s Foundation Seeds, Asgrow and DeKalb.

A central Illinois farmer takes a look at an ear of corn on his farm near Mazon, Ill.

“Independent seed corn companies, they’re not around anymore,” Brauer said. “They’ve been bought up by Monsanto.”

The American Antitrust Institute — an independent and nonprofit organization based in Washington D.C. — concluded that the pending third wave of mergers and acquisitions would likely eliminate any remaining head-to-head competition and severely reduce innovation. Texas A&M University’s research stated increased concentration in the seed industry has already slowed the intensity of private research funding.

“The more competition there is, the lower the prices, the better the quality, the more innovation there is,” Waller said. “The fear is that price is going to go up, quality is going to go down, and whichever company was trying super hard before, well, they got merged in, and they’re going to stop caring.”

The Justice Department cited similar innovation concerns when it announced in August that it is challenging an agribusiness deal in which Deere & Co. is trying to buy Monsanto’s precision-planting division.

Despite concerns, economic models predict that — if the deals were to become final — seed prices, by and large, wouldn’t be largely affected.

Monsanto Chief Technology Officer Robb Fraley speaks to reporters at a company research facilities near St. Louis on Jan. 29, 2016.

The price of corn and soybean seed are both projected to increase by less than 3 percent.

Additionally, corporate executives say the deals would not lead to diminished innovation spending in the future. In fact, executives claim mergers would help innovation flourish because companies could pool research and funding. Plus, they say, farmers are constantly looking for new products to help them counter pesticide-resistant weeds and the effects of climate change. That means companies will always need to invest in research and development to manufacture desirable products and turn profits.

“We are committed to continued innovation,” said Tim Hassinger, president and CEO of Dow AgroSciences, while giving his Senate testimony on Sept. 20. “Innovation drives this industry and, simply said, we could not remain competitive without significant investment in R&D.”

Monsanto, Bayer, Dow Chemical, DuPont, Syngenta AG and BASF — the Big Six — invested more than $13 billion in research and development in 2015, financial reports show.

Executives have also promised to continue open-licensing, which allows competing companies to borrow from one another’s gene traits inventory. The bulk of that open licensing is only shared among the Big Six, though, and some analysts have compared the setup to cartel-like behavior.

“The consolidation has already happened, and if we were going to have hearings on it, then that should have been years ago… That’s when the competition got weeded out.” – Norbert Brauer, Illinois farmer

The Syngenta facility in Paris, Ill., on Dec. 9, 2014.

Photo Credit: Darrell Hoemann/Big-AgWatch.org

Industry says overregulation triggers consolidation

Seed companies spend tens of millions of dollars bringing new types of GMO seeds to market — and that costly process can take anywhere from five to 13 years.

In the United States, GMO seeds are regulated under what is known as the coordinated framework for biotechnology, an oversight system administered by the USDA, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Food and Drug Administration. The system has been around since 1986, but officials are in the process of modernizing it.

Agriculture industry representatives argue the regulatory framework is burdensome and has obstructed innovation.

“The length and rigor of the regulatory process have certainly caused some cost increases for these companies, and that’s probably the single biggest item that would be stifling innovation,” Nelsen said. “Regulations and increased biotech and chemical scrutiny are part of the reason why companies are getting bigger.”

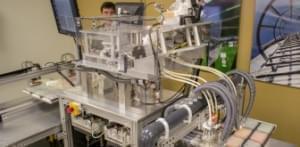

A seed-chipping machine at a Monsanto research facility near St. Louis.

The USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services — just one part of the framework — is in charge of making sure new seed biotechnology products aren’t “pests” that could potentially harm plants or animals once commercially grown. Companies need to submit formal petitions asking the agency to deregulate new biotechnology products before they can sell them to farmers.

“I think [regulation] has caused companies that have been in this industry some tough times,” Nelsen said.

The demanding regulation has also brought slow financial returns and created a barrier of entry for startup seed firms looking to join the market, according to the Texas A&M University research. That, in turn, is another reason why seed and chemical companies have gotten larger — they’re better at cutting through the red tape.

In its history, the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services has approved more than 150 petitions, records show.

Monsanto was the sole applicant in about a quarter of those winning petitions, more than any other organization.

“As someone who grew up on a small family farm in Illinois, I understand that change can be unsettling to farmers,” Monsanto Chief Technology Officer and 2013 World Food Prize recipient Robb Fraley said in his Senate testimony. “But our industry is changing, and it needs to, because the solutions we need can only come if companies embrace new technology, increase their investments and accelerate research and development.”

“That’s why you are seeing the latest rounds of mergers right now,” he added.

Brauer said that he has had a bountiful 2016 harvest and that he isn’t overly stressed about the industry consolidation. His most pressing concern isn’t Bayer teaming up with Monsanto or Syngenta being bought out by ChemChina, he said, but rather the low prices he’s receiving for his crops.

“Frankly, I don’t see that any of these deals are really going to hurt us anymore than what we’ve been hurt,” Brauer said.

"This story was updated on Dec. 9, 2016 to correct the name of the award given to Robb Faley in 2013 as the World Food Prize, not World Food Price."

Big Ag Watch is a project of The Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting, an independent and nonprofit newsroom devoted to educating the public about crucial issues in the Midwest with a special focus on agribusiness.

The agribusiness industry includes several billion-dollar businesses, many of which are key players when it comes to food, fuel, environment, labor and energy. On top of that, the agribusiness industry nets hundreds of millions of dollars in government subsidies, while also influencing local, state and federal policies.

At the industry’s helm are a handful of multinational companies, many based in the Midwest.

Through original reporting and innovative tools, Big Ag Watch will be devoted to scrutinizing those companies and measuring their impact.

Please contribute your tips and ideas for news coverage to tips@big-agwatch.org.