Why Don’t More Doctors Help Cancer Patients Quit Smoking?

Pixabay/Alexas_Fotos (CC0)

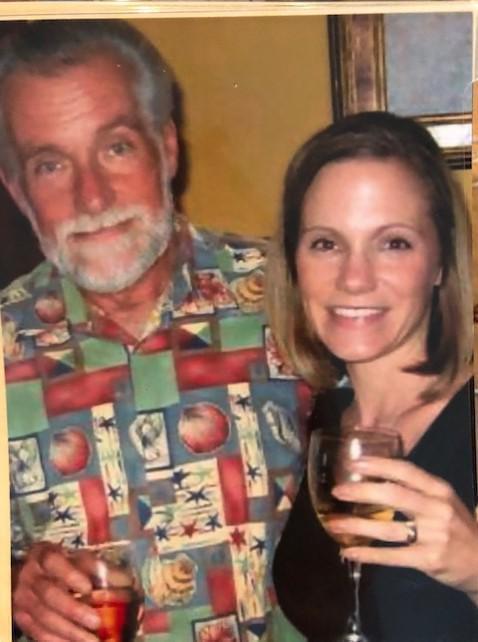

Most people knew James Strain as “Butch.” Dr. Cynthia Meneghini called him “Dad." She remembers him as a handyman who could fix anything. When she moved to a new house, he painted it top to bottom, despite feeling pain in his ribs.

Dr. Cynthia Meneghini and her father, James Strain.

“He thought it was because he always fixed cars and he thought he was rolling under cars all the time he probably hurt his rib that way. But it turned out it was lung cancer that had already metastasized to his bone,” says Meneghini, a physician with Community Health Network in Indianapolis.

“The daughter in me knew that was bad, but the physician in me knew that was really, really bad – stage four non-small cell lung cancer,” she adds.

More than 150,000 Americans die from lung cancer each year. And smoking is responsible for up to 90 percent of those deaths.

Despite the high stakes, many people – including Meneghini’s father – keep smoking after getting a cancer diagnosis. Strain died at age 73, two years after finding out he had cancer.

“Most smokers enter and leave their cancer care without getting help quitting,” says Dr. Michael Fiore, director of the University of Wisconsin Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention.

In a recent commentary for the New England Journal of Medicine, he wrote that about half of cancer patients are smokers when they are diagnosed.

“Until recently, we didn’t realize how beneficial it is to quit immediately upon getting a cancer diagnosis,” Fiore says.

Research shows cancer patients who quit smoking respond better to treatment. They tolerate chemotherapy better and have fewer surgical complications. And they’re more likely to survive cancer, and less likely to get cancer again.

But research also shows many cancer treatment programs don’t include support to help patients quit smoking.

“It used to be the old view is that you already have cancer. And it doesn't matter you just keep smoking it doesn't matter anymore. And that’s completely wrong,” says Graham Warren, a researcher at the Medical University of South Carolina. “You can’t wait until after treatment is over to start looking at it. You really need combine it with your first-line cancer care.”

Warren's research found most oncologists ask patients if they smoke and tell them to stop. But fewer than half provide direct support to quit. Instead, doctors focus on treating cancer.

“Patients can receive treatment from the oncologists, but in a health care setting now it’s very difficult for oncologists to provide cessation support with everything else,” Warren says.

Researcher Lisa Carter-Harris of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York says many smokers don’t even tell their doctor they smoke for fear of being blamed for their illness.

She says patients will tell their doctors, "'Don’t they know that I know that? I want to stop smoking. I need help and I need empathy I don’t need someone giving me a lecture.' There is an implicit bias out there that exists around smokers, and that makes the patient not want to engage.”

To bridge the communication gap, some cancer treatment centers now have programs to help patients quit smoking. Last year, the National Cancer Institute funded a program at the Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Cancer Center in Indianapolis.

As of 2016, 21 percent of Indiana adults were smokers, according to the CDC. That's higher than the U.S. rate of 15.5 percent among adults.

The Indianapolis center is one of 42 funded by the NCI nationwide and one of a handful in the Midwest, including Case Comprehensive Cancer Center in Cleveland, Ohio; Markey Cancer Center in Lexington, Ky.; Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center and the University of Chicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chicago, Ill.; and Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center in St. Louis, Mo.

“We’re being more active about it as opposed to passive about reaching all of the patients who are smokers,” says Dr. Mimi Ceppa, a thoracic surgeon at the Simon Cancer Center.

New patients are asked for a detailed medical history. Smokers are flagged in the electronic records system.

“We can now use electronic health records, for example, to systematically prompt clinicians to give succinct effective treatments once they know they’ve got a patient who smokes in front of them,” Fiore says.

Then a doctor like Ceppa can start a conversation about quitting and refer the patient to treatment. That includes everything from getting nicotine replacement therapy like patches or gum to prescribing medicine at a pharmacy that doesn’t sell cigarettes.

“The treatment plan for each patient gets personalized to what is best and what will most likely be successful for each patient,” Ceppa says.

Doctors hope intervening in more patients’ care means fewer patients return to the center.

Fiore says, “We need to seize that moment that a cancer patient comes in for cancer care and wrap smoking cessation up as part of that cancer care, because it truly is.”

This story was produced by Side Effects Public Media, a news collaborative covering public health.

Public health officials are concerned about the impact of rising rates of teen e-cigarette use. Side Effects will hold a live streamed panel conversation on the topic of youth vaping on June 4. A panel of experts will address comments and answer questions. Please register here.