U.S. County Jails Step Up Mental Health Screening To Keep Inmates From Coming Back

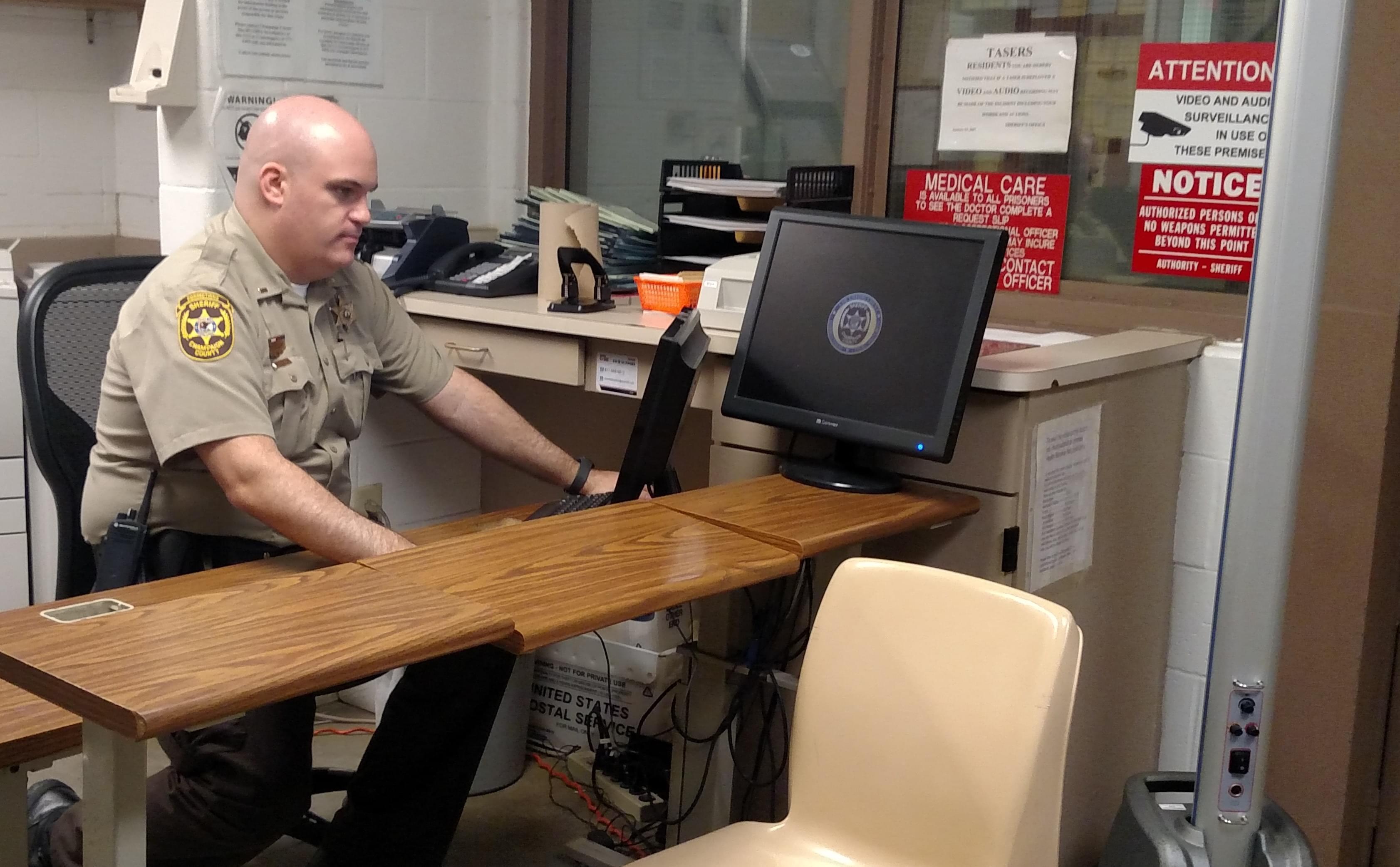

Champaign County Jail Lieutenant Ryan Snyder says a shortage of community-based mental health services creates a difficult scenario for law enforcement, as more people with mental illnesses end up in jail. Christine Herman/Illinois Public Media

DeVonte Jones began to show signs of schizophrenia as a teenager. His first public episode was nine years ago at a ball game at Wavering Park in Quincy, Illinois.

“He snapped out and just went around and started kicking people,” said Jones’ mother Linda Colon, who now lives in Midlothian in the Chicago suburbs.

The police were called. Jones was arrested, charged with aggravated battery and placed in Adams County Jail. Colon said Jones had no recollection of what happened.

Her son got out on probation and went to therapy. He started on medications, but Colon said they didn’t help. When he got caught self-medicating with marijuana, he ended up back in jail.

Jones has been in and out of jail ever since. He’s among the estimated half a million people who are incarcerated in the U.S. and have a mental illness.

In recent years, county jails across the nation have taken steps to try to keep inmates with mental illness, like Jones, from coming back. One approach involves stepped up mental health screening, coupled with efforts to get inmates plugged into community-based treatment after they are released. Such efforts require often-unprecedented collaboration between those on the frontlines of mental health and criminal justice. But research shows such collaboration is key to addressing the problems many jails face when they become their communities’ largest psychiatric facilities.

Indeed, Colon said the jail conditions caused her son’s condition to worsen. She said he lost access to his medications and would experience schizophrenic episodes that landed him alone in a cell.

“But if you’re a mental illness patient, there’s no way to calm yourself down without any kind of medication or therapy,” said Colon, who has been in jail herself and is currently out on probation.

Lieutenant Ryan Snyder sits at a desk in the intake area of the Champaign county jail, where an evidence-based mental health screen is used to flag inmates who may have a serious mental illness.

Adams County Sheriff Brian Vonderhaar said he could not comment on Jones’ situation because he didn’t work in the jail back then. But he said all inmates are screened for mental illness and the jail’s medical providers administer medications as needed. Inmates who are suicidal may be placed alone in a cell with only a mat and a garment that cannot be used for self harm.

Real Change Needed

One in four jail inmates shows signs of a serious mental illness. But the most recent federal data finds two-thirds of them never receive treatment, even though adequate health care in jail is a constitutional right.

Efforts to reduce the number of inmates with mental illness need to involve the jail system, since it is “the front end of the criminal justice system,” said Richard Cho of the Council for State Governments Justice Center.

In 2015, the CSG Justice Center, together with the National Association of Counties and the American Psychiatric Association Foundation, launched the Stepping Up Initiative to help jails reduce the number of inmates with mental illness..

More than 400 counties have passed resolutions to join the program, which promotes the use of evidence-based screening tools to identify inmates who have a serious mental illness. Inmates who screen positive are referred to a clinician for a follow-up assessment. The CSG Justice Center provides counties with technical assistance to collect data to understand the scope of the problem and determine whether efforts to reduce the number of inmates with mental illness are working.

The Champaign County Jail signed onto the Stepping Up Initiative after Deputy Chief Allen Jones realized the majority of the jail’s “frequent flyers,” who landed in jail five or more times a year, had mental health or substance use issues.

Connecting Inmates To Care

Since then, Deputy Chief Jones implemented a mental health screening tool as part of the intake process. The jail partners with Rosecrance, a community-based mental health treatment provider, which receives funding from the county to send caseworkers to the jail to help inmates get plugged into treatment after they’re released. The Champaign County Health Care Consumers, led by Claudia Lennhoff, also sends people to the jail to help inmates sign up for health insurance, to ensure the care they seek in the community will be covered.

“It’s very hard for a lot of communities to do this kind of work because you [often] don’t have partners like the Sheriff’s office willing to cooperate,” Lennhoff said. “A lot of what we’re doing is building trust so that people know that help is available.”

Lennhoff said many inmates get connected to care for the first time through the jail.

Pam Rodriguez is the CEO of TASC-Illinois, an organization that helps inmates re-enter society. She agrees with Lennhoff that jail can be a turning point for people with untreated mental illnesses. But she said it’s a shame those people didn’t find help sooner.

“These are people who were noticed in school, I’m almost certain,” and didn’t receive help, Rodriguez said. “These are people whose families have probably tried to get them into care.”

Ideally, Rodriguez said people with mental illness who get arrested would be diverted to treatment instead of jail where their condition can worsen. “People with mental illness often end up in cells by themselves,” she said.

A cell in the Champaign County Jail that may be used to house inmates who are suicidal. For their safety, Lieutenant Ryan Snyder says they would be placed alone in the cell with nothing but a mat and a garment that cannot be used to cause self-harm.

On one hand, Rodriguez said, isolation can prevent a mentally ill inmate from being victimized. Federal data finds inmates who show signs of serious mental illness are at higher risk of sexual victimization by another inmate.

“But isolation tends to exacerbate mental illness,” Rodriguez said. “Then the jail, which is not prepared to deal with serious mental illness, has to figure out what to do. And that’s a huge challenge.”

Roadblocks To Mental Healthcare

To keep people with mental illness out of jail entirely, Cho said the U.S. needs a mental health system that destigmatizes mental illness “and is able to identify people at the very first onset of their symptoms for mental health. We’re so far from that in this country,” he said.

Across the U.S., community resources for mental health are stretched thin. In Illinois, mental health services took a hit over the last several years. Lawmakers went months without paying providers who were promised state funding. That led to behavioral health agencies reducing services; some permanently closed their doors.

Champaign County Lieutenant Ryan Snyder said this has created a challenging situation for law enforcement. "The mental illness leads to them committing these crimes and there's really no place else for them to go, so they come here,” he said.

“This is not a hospital. This is a jail,” Snyder said. “You do the best you can.”

But he said it's not easy for any jail to provide the kind of one-on-one mental health treatment many inmates need.

In the omnibus bill approved by Congress in March, appropriations for the Department of Justice’s Mentally Ill Offender Treatment and Crime Reduction Act more than doubled to $30 million compared to the previous year. The Act was initially authorized by Congress in 2004 to facilitate collaborations among the criminal justice, juvenile justice and mental health and substance use treatment centers, like the one in Champaign County.

Looking Ahead

Deputy Chief Jones is applying for federal funding to hire more caseworkers who can help police officers handle calls for mental health crises in Champaign County. He’s working with academic researchers to find out how efforts to reduce the number of inmates with mental illness in the jail are doing.

“I don’t know how to fix societal issues,” Jones said. “But I’m trying to find ways to get the best outcome that we can get.”

In Adams County, Sheriff Vonderhaar said the jail is developing a mental health court that would divert people with mental illness into treatment instead of jail. The county is also building a new jail facility with a layout that would allow for new programs for inmates such as support groups for drug addiction, mental health counseling and GED classes.

Meanwhile, Linda Colon’s son DeVonte Jones is now 24 and back in jail. This time in Livingston County. He’s charged with production and possession of child pornography and is awaiting sentencing. Colon said he takes medications but is still not well.

“He’s attempted suicide a few times,” she said. “So for me, out here as a parent, I’m wondering if I’m ever going to get that phone call one day saying that they went to my son’s cell and found him not alive.”

Colon said she can’t help but wonder if the right interventions earlier on would have kept her son out of the system.

For now, she does what she can to help him stay positive. Jones calls him almost everyday, and she reminds him that she loves and accepts him unconditionally.

“I just really hope that he doesn’t get so low that he gives up,” Colon said.

This story was produced by Side Effects Public Media, a news collaborative covering public health.

Follow Christine on Twitter: @CTHerman

Links

- Illinois Prison Staff Trained On Mental Illness, But Do They Really Buy In?

- There Are Still Not Enough Beds For Prisoners With Mental Illness

- Living with Mental Illness in Central Illinois: A WILL News Special

- A Mother And Son Live, And Cope, With Mental Illness

- The Science of Medication in Treating Mental Illnesses