Who Should Decide If A Charter School Can Open?

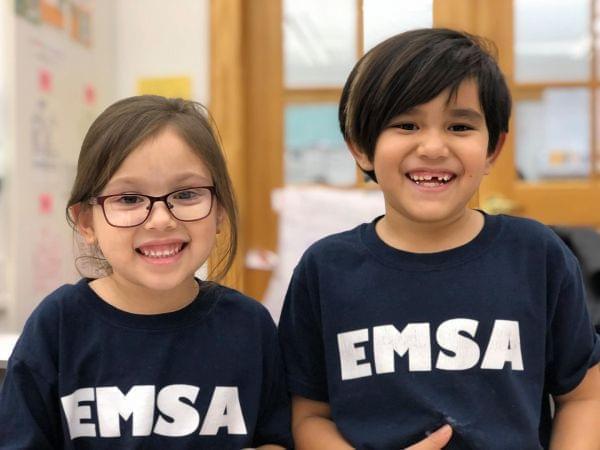

A state commission overruled Elgin's locally-elected school board to allow Elgin Math and Science charter school to open. Elgin Math & Science Academy/Facebook

Last spring, Illinois lawmakers approved legislation that would strip a state commission of its power to overrule local school boards. But after Gov. Bruce Rauner vetoed the bill, some state senators changed their positions, while others disappeared from view.

The vote came late on a Wednesday afternoon. It was below freezing in Springfield, and starting to snow in Chicago. Did that matter? Maybe.

“There were people sitting in their chairs who were ‘yeses’ last time who did not vote,” says Sean Denney, the lobbyist who has been pushing this bill for six years.

“And there were ‘yeses’ that had been in the chamber moments before who were suddenly gone…. There were yes votes sitting in their office with their door closed, who also were not on the floor when it happened.”

Denney lobbies for the Illinois Education Association, the largest teachers union in the state. He has filed a version of this proposal before, and but this bill took a funny path. Some state representatives who had initially voted nay instead pushed their yea buttons to reject the governor’s veto, seemingly setting the stage for an easy override in the Senate, where the bill had originally won 36 votes — a veto-proof majority.

But when the override was called, only 31 Senators voted yes, 14 voted no, and another 14 didn’t vote at all.

What made this bill so controversial? It’s all about charter schools.

Most charters are public schools, but they’re privately operated — ideally to serve as a sort of laboratory to try out new innovative educational strategies. Unions have long been opposed to charter schools, because most charters don’t allow their teachers to unionize. However, that situation has been changing, and in fact, one of the largest chain of charters in Chicago, Acero Schools, is currently on strike. (Editor's note, teachers reached a tentative agreement to end the strike early Sunday).

But unions representing public school teachers have other concerns about charter schools: Charters divert money from neighborhood schools.

“The way that the funding works for charter schools is the state sends money to the local district, and if there’s a charter school in the district, they basically just lop off the money for the charter school,” Denney says.

The amount lopped off for the charter is calculated on a per-student basis. So each student enrolled in a charter diverts money from the home district.

“And just because the student leaves doesn’t mean the electricity bills go down, or other costs that are associated with running a school,” Denney says. “Those costs remain, and the student has taken some of the funding that goes along with it. It leaves the local district in the arrears, without question.”

That’s the reason charter operators hoping to open new schools have to seek approval from the local school board. If the school board denies a charter application, the charter operator can appeal to the State Charter School Commission — nine people appointed by the governor. Under current law, the commission’s decision trumps the local school board’s. Denney’s bill would’ve taken away the commission’s power.

State Sen. Chuck Weaver (R-Peoria), whose daughter has taught in a charter school, argued on the Senate floor that the commission has rarely overruled a local school board, and that on those few occasions, it was because the local trustees were just wrong.

“It’s really important to underserved districts, and while we all support local control, there are times the local school board acts in error,” Weaver said.

But Denney points out the commission doesn’t typically reject an applicant outright; it simply responds with suggestions on how they can improve their application and try again. And he disputes Weaver’s assertion that the state commission knows what’s best for local communities.

“From our viewpoint, if you overturn a single locally-elected school board on one of the biggest decisions that they’re elected to make, that’s one too many,” Denney says.

Here’s an example: The commission overruled the school board of Elgin’s Unit 46, the state’s second largest district, to allow Elgin Math and Science Academy to open last fall. Unit 46 CEO Tony Sanders says the charter isn’t even located within the U-46 attendance zone, but his district has already had to send $2 million to the charter. Since the charter plans to add another grade level each year, that amount will grow annually.

Once a charter is up and running, it’s tough to uproot, because families become passionate about their schools. State Sen. Iris Martinez (D-Chicago) says she chose to sit in her seat and vote to uphold Rauner’s veto because parents in her district want her to protect their charter schools.

“I’m going to support whatever the parents in my neighborhoods want for their children,” she says. “This is about the parents. This is about the choices parents make when it comes to education, and we need to respect that.”

Some observers have noted that the political action committee associated with the Illinois Network of Charter Schools has amassed a $2 million warchest, and suggest that potential for campaign contributions could have influenced veto override votes. Others have figured Senators just watched weather reports and were anxious to get back to Chicago before it was covered in snow.

Whatever it was, Denney says he’ll bring his bill back next session. With a new Democratic governor and more Democratic lawmakers, he says the time is right to re-file his old bill, which will restrict the commission’s power even more.

“The political situation has changed,” he says, “and now we can come forward with a better bill that actually not only remedies the problem moving forward, but also takes care of things that have happened in the past.”

Links

- Champaign Unit 4 Board Denies Charter School Proposal

- Unit 4 School Board To Vote Wednesday On Resolution To Deny Charter School

- Questions Raised About Champaign Charter School Proposal

- Culture Shock: Teachers Call Noble Charters ‘Dehumanizing’

- Champaign Charter School Proposal Aims To Close Racial Achievement Gap