Illinois Issues: The Trouble With Temp Work

A Warehouse Workers for Justice rally. Warehouse Workers for Justice

Isaura Martinez was working at a Bolingbrook factory when she felt a pull in her left wrist as she was attaching a metal hook to the back of a Christmas card holder. Four years have passed, but the Cicero woman still feels pain, after surgery to correct the issue.

She was a temporary worker hired out by a staffing agency at the time of the injury. Every worker, she says, was required to do a variety of tasks, such as packaging coffee and tobacco and assembling cardboard boxes for toothpaste. Because she was employed through a staffing agency, it was unclear to her who was responsible for overseeing training and other working conditions.

She says the staffing agency had her work with an injured wrist for three months without restrictions, until she sued the firm.

Isaura Martinez sits besides Rep. Carol Ammons (in yellow) during a labor committee hearing.

Speaking before an Illinois House committee in March, she detailed some of the hardships endured by temporary workers. “Most of the times we don’t get equipment like gloves, hats or different equipment to open pallets … all we want is for us to be given the tools that we need to work.”

Temporary workers find themselves at the intersection of a growing manufacturing and e-commerce industry in which companies increasingly enlist third-party agencies to do hiring on their behalf. It is an issue particularly for Illinois, which Mark Meinster, executive director of the Joliet-based Warehouse Workers for Justice, described “as the warehousing capital of the western hemisphere.”

This concentration of the industry in Illinois is “due to the fact that Chicago is the only place in the world where six Class 1 railroads meet” along with seven interstate highways where products are hauled by truck throughout the United States, a 2014 study by the National Employment Law Project concluded.

"Because you have a lot of warehouses you have a lot of temp workers," Meinster says. "And so, Illinois really needs to be cutting edge when it comes to legislation protecting those workers.''

In Chicago alone, 63 percent of warehouse workers are temporary workers. According to EMSI, a private labor market research firm, between 2009 and 2013, Chicago saw a gain of 45,000 temporary jobs, which accounts for 40 percent of the positions added to the economy during that time.

This is a competitive business where the lines are blurred between a staffing agency and the “client” company where the final product is being assembled or packaged. The resulting model is one where responsibilities are divided and shared.

Some call this a “shell game.” The staffing agency may handle paycheck issues but not the working conditions in a factory or warehouse. The agency screens temporary workers and pairs them to available work but can only guarantee work at the client company’s discretion on a day-to-day basis. As a result, the staffing agency industry — while growing — struggles to keep a lucrative business.

This “low-margin business for staffing agencies” forces them to "cut corners,” Meinster says.

“Because staffing agencies only do one thing: provide labor, the corners that get cut tend to be worker’s wages, worker’s comp coverage. Some temp agencies have been gone after because of payroll tax violations — so in order to compete, because the margins are so low, temp agencies are almost forced to break the law,” he says.

Warehouse Workers for Justice conducts a rally for improved conditions for temporary employees. Walmart spokesmen did not respond to requests for comment.

According to labor rights advocates, Illinois staffing agencies have been known to charge temporary workers for their own background checks and drug tests as a way to cut back on their operating costs. Some agencies have been sued for discriminatory practices in hiring because they based screenings on race and gender. Others have gone to court for wage theft. And to continue providing temporary workers to the industry, these staffing agencies will not try to help their workers get into permanent jobs, say temporary worker rights advocates.

There were more than 840,000 workers employed by staffing agencies in Illinois in 2015, according to the American Staffing Association. That breaks down to 174,350, temporary workers each week or an average of 3.2 million in the United States each week.

In an attempt to address temporary worker issues, an Illinois legislator introduced a bill that would amend an existing Illinois Day and Temporary Services Act, which is considered to already be one of the most comprehensive laws regulating staffing agencies in the country. But major amendments to the Illinois Day and Temporary Services Act have failed to get approval by the General Assembly since 2007.

This proposed legislation faces opposition from several staffing agencies in the state. And several legislators say they are unsure whether additional enforcement through legislation is needed.

Democratic Representative Carol Ammons of Urbana says House Bill 690’s language has changed as negotiations with the opposing staffing agencies have continued. Ammons says the bill’s original language contained provisions to end wage theft, gender and race hiring discrimination, and issues of safety and health hazards.

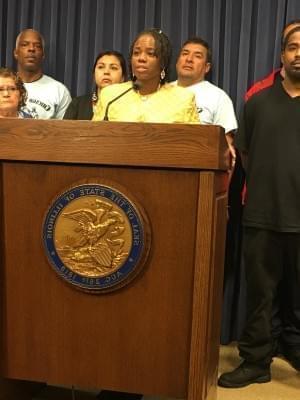

Rep. Carol Ammons, an Urbana Democrat, speaks at a press conference about her bill that aims to protect temporary worker rights. A group of temporary workers stand with her.

“What the bill does, at this point, of which we have attempted to negotiate in good faith with the staffing agencies—[is to close] a few, small loopholes,” Ammons testified in front of a Labor House Committee. The amended bill would now change the minimum penalties for health and safety violations, which are currently at zero, and raise them to $50. The bill would require staffing agencies to report demographic information about the workers that they hire, and it encourages staffing agencies to make attempts to place their temporary workers into permanent positions. It would also prevent agencies from charging for background checks, drug tests and credit checks.

The Department of Employment Security estimates that a new program and system to track compliance with the bill will cost between $3.5 million and $7 million to create. The program would need “an online submission component, an interagency connection to the Department of Labor and a revenue collection component,” according to the department. In addition, four to eight full-time employees will be needed to oversee the initial creation, and four to six full-time employees to run the program. Annual costs are estimated to run from $500,000 to $750,000.

One opponent is the Staffing Services Association of Illinois, made up of 25 staffing agencies. Dan Shomon, lobbyist for this association, says that there are already federal and state-level laws that address the bill’s concerns of discrimination. He said during the Labor Committee that Rep. Ammons’ proposed bill “will result in less jobs and opportunities in Illinois.”

“This legislation, most importantly, expands the private right of action, which will surely mean more private litigation by plaintiff’s firms that regularly sue staffing agencies,” he said during testimony.

“Currently, there are a few complaints against our member companies with the Illinois Department of Labor,” said Shomon. “The few that have been — sometimes there is wage and hour issues, which we resolved. Nothing has ever gone to court from the Department of Labor. In other words — no specific case in the last five years.”

But just because complaints have not been addressed by the labor department, does not mean that the violations and complaints don’t exist, Ammons says.

Warehouse Workers for Justice conducts a rally aimed at Walmart practices. The merchandising giant did not respond to requests for comment.

Isaura Martinez, the temporary worker injured at a manufacturing plant, was once hired by Elite Staffing Inc. an Illinois-based staffing agency, and part of the 25 agencies that the Staffing Services Association of Illinois represents.

During her testimony at the bill’s hearing, Martinez described how Elite Staffing employees would drive more than 20 temp workers in charter buses from one client company to another until they were selected by a warehouse manager for work. She also experienced lack of training, which resulted in work injuries.

Elite Staffing has been embroiled in lawsuits over the last few years. Meinster from the Warehouse Workers for Justice says Elite Staffing is known as “one of the worst staffing agencies in the state of Illinois, that’s why it’s suffered many lawsuits and Department of Labor complaints.” The organization referred Illinois Issues to Shomon for a response to the accusations. “That’s just an unsubstantiated claim,’’ he said of Meinster’s comments. "Our association is trying to work with Rep. Ammons to get temporary workers into permanent jobs.”

Illinois Issues obtained a list of wage claim complaints against staffing agencies submitted between 2014 and 2016. The list has 148 complaints investigated by the Labor Department and their status. According to the list, 12 wage complaints against Elite Staffing have been reviewed and three have been dismissed. Elite Staffing paid the remaining nine claims.

In March, Elite Staffing settled for $965,000 a class action lawsuit for alleged labor violations. The agency settled with 112,136 temporary workers employed by the agency from April 13, 2012 through April 13, 2015.

Republican Rep. Jeanne Ives of Wheaton, who voted against the bill in committee, said Ammons’ bill would not correct federal violations taking place at the client company’s warehouses or factories, which she says, can already by addressed existing federal and state-level laws.

At the federal level, there is no overall law protecting temporary workers, says Rebecca Smith, deputy director of the National Employment Law Project, a New York-based labor advocacy and research group. This is why state-level legislation is needed to close loopholes, she says.

Current federal labor laws assign responsibility to employers, so when temp agencies take on the role as employer, “they become the people who are in charge of compliance with health and safety standards, with federal minimum wage law, complying with the National Labor Relations Act giving workers a voice at work,” Smith says. At the state level, these temp agencies are in charge of paying unemployment insurance premiums and workers’ compensation premiums as well as complying with any state-level labor laws.

Shomon, lobbyist for the Staffing Services Association of Illinois, agreed with Ives in that work violation penalties should not fall on the hiring agency alone. This is a thought echoed by Smith but she says that the relationship between the client companies, the staffing agency, as well as with the temporary worker, allows for responsibilities to fall back on the hiring agency.

The staffing agencies are “competing for business of major corporations that will offload responsibility onto the temp agency,” she explains.

The current Illinois Day and Temporary Services Act and the proposed amendments under Ammons’ bill restore the balance between the client company and the staffing agency, Smith says. This will limit the temptation of businesses to push their responsibility as employers off on to a temp agency and prevent the domino effect of what she described as “squeeze [ing] the temp agency, which in turn squeezes the workers.”

Rebecca Smith is deputy director of the National Employment Law Project.

But with these multiple layers of contracts and ambiguity, a temporary worker is left wondering where to direct concerns and complaints. In addition, there are fears of retaliation and dismissal because temporary workers do not have the same employment protections as a direct-hire worker does.

As of 2016, the Illinois Department of Labor lists more than 300 corporate offices with over 700 branches registered with the state to hire on behalf of other companies. The original Illinois Day and Temporary Services Act forces staffing agencies to register their business with the Labor Department. There is a $500 fee to client companies if they hire a staffing agency not registered with the state.

These staffing agencies are hired by a variety of businesses, including large retail and supply chains that need workers to staff their warehouses and manufacturing and production companies that need workers to overlook quality control.

Large corporation distribution centers continue to grow in Illinois. Amazon announced last year that the company will add two fulfillment centers in west suburban Aurora. This is in addition to the six existing or already planned fulfillment centers around the state.

Through the state’s Economic Development for a Growing Economy Tax Credit Program (EDGE), Amazon has been able to benefit from “special tax incentives” that encourage companies to locate or expand their operations in Illinois, according to the Illinois Department of Commerce & Economic Opportunity website.

And while these large retailers and supply chains flaunt full-time job opportunities, there will still be many workers in temporary positions, says Meinster.

The temporary work industry—the warehouse industry, used to be a good industry to work for, he says.

“Those used to be good jobs, mostly union jobs, living wage jobs, benefits, pensions, but over the last couple of decades we’ve seen this shift toward these large, global supply chains that are driven more by retailers like Walmart, Home Depot, Amazon that are really dedicated to getting goods into the U.S. market as quickly and as cheaply as possible.”

Staffing agencies will continue to meet the needs of these large supply chains that need to provide customer fulfillment in an industry that demands shorter delivery times. And temporary workers will be expected to meet the staffing needs for these fulfillment centers.

Addressing the House Labor Committee, Isaura Martinez, the temporary worker injured in a factory, asked legislators to take her experiences and that of her co-workers into consideration when voting for the bill, which passed out of committee with a 17-8 vote.

“In each of your homes,” she told the committee, “there is a product that comes out of a factory where temporary workers are suffering.”

Links

- U of I Building & Food Service Workers Ratify 3-Year Contract

- U Of I: Not Clear How AG’s Filing Impacts University Workers

- Domestic Workers Protected Under New Illinois Law; Stopgap Budget Expires

- Without Congressional Action, Retired Coal Workers Could Lose Benefits By End Of 2016

- Illinois Suspends No-Overtime Policy For Home Care Workers

- Governor Rauner Vetoes Pay Hikes For Construction, Home Healthcare Workers

- Rauner Pushes Workers’ Comp Reform In Bloomington

- SEIU Healthcare Sues To Force State Pay On Workers’ Health

- State’s High Court Asked To Decide Whether Workers Can Keep Getting Paid