Illinois Issues: Opening Minds Behind Bars

Students, teachers, staff and volunteers posed for a picture after a convocation ceremony for the fall semester of a masters degree program at Stateville Correctional Center. Karl Soderstrom

Ro’Derick Zavala grew up in Chicago at 21st and State Street — the northern tip of a four-mile corridor lined with 8,000 units of public housing. His mother worked three jobs, including one at Walgreens, where she would pick up the Disney and Hanna Barbera books that inspired Zavala to fall in love with reading at a young age.

That passion should’ve made him a successful student. But on Chicago’s south side, in the 1980s, it was hard to find a safe place to go to school.

“My mother was always trying to get me out of the neighborhood I grew up in, so we constantly moved a lot. I was never in a school longer than a year," he says. "So you take me from one neighborhood to another school … to her, the school seems like a better place to go. But there still is a neighborhood around it that I have to operate in. So I continued to get in trouble in school and get kicked out of school.

"I don’t blame anyone for my actions; those were my actions," Zavala says. "And I tell people now, you know, if you raise a child in a war zone, that’s all the child knows is war. But if you take that same child out of that war zone, and you introduce him to people with new ideas and new things, and you allow that child to flourish, then you have a completely different person.”

Stateville is known for its "roundhouse" arrangement of cells. This portion of the prison is no longer in use.

Zavala has finally found a place to learn new ideas and flourish. Ironically, it’s inside Stateville Correctional Center, a maximum-security prison near Joliet, where Zavala is about halfway through a 40-year sentence. Despite dropping out of school at age 15, he’s on the path to earning a master’s degree through North Park University.

Michelle Clifton-Soderstrom directs the program.

“We started piloting classes about four years ago, because, well, for me, I was teaching social ethics and getting frustrated with just teaching topics that weren’t actually making change on the ground," she says. "So we decided that teaching in prison would be a great place.”

North Park University is a private college founded by the Evangelical Covenant Church. There are other church-sponsored prison education programs in other states, but three things set this one apart: For starters, it offers an accredited degree. North Park obtained approval from the Association of Theological Schools and the Higher Learning Commission to offer a masters of art in Christian ministry with an emphasis in restorative arts (a broader interpretation of restorative justice). And because it’s a rigorous four-year program, they can accept students who don’t have a bachelor’s degree.

You don’t have to be a felon to get this deal. North Park also accepts a few students from the free world into this program.

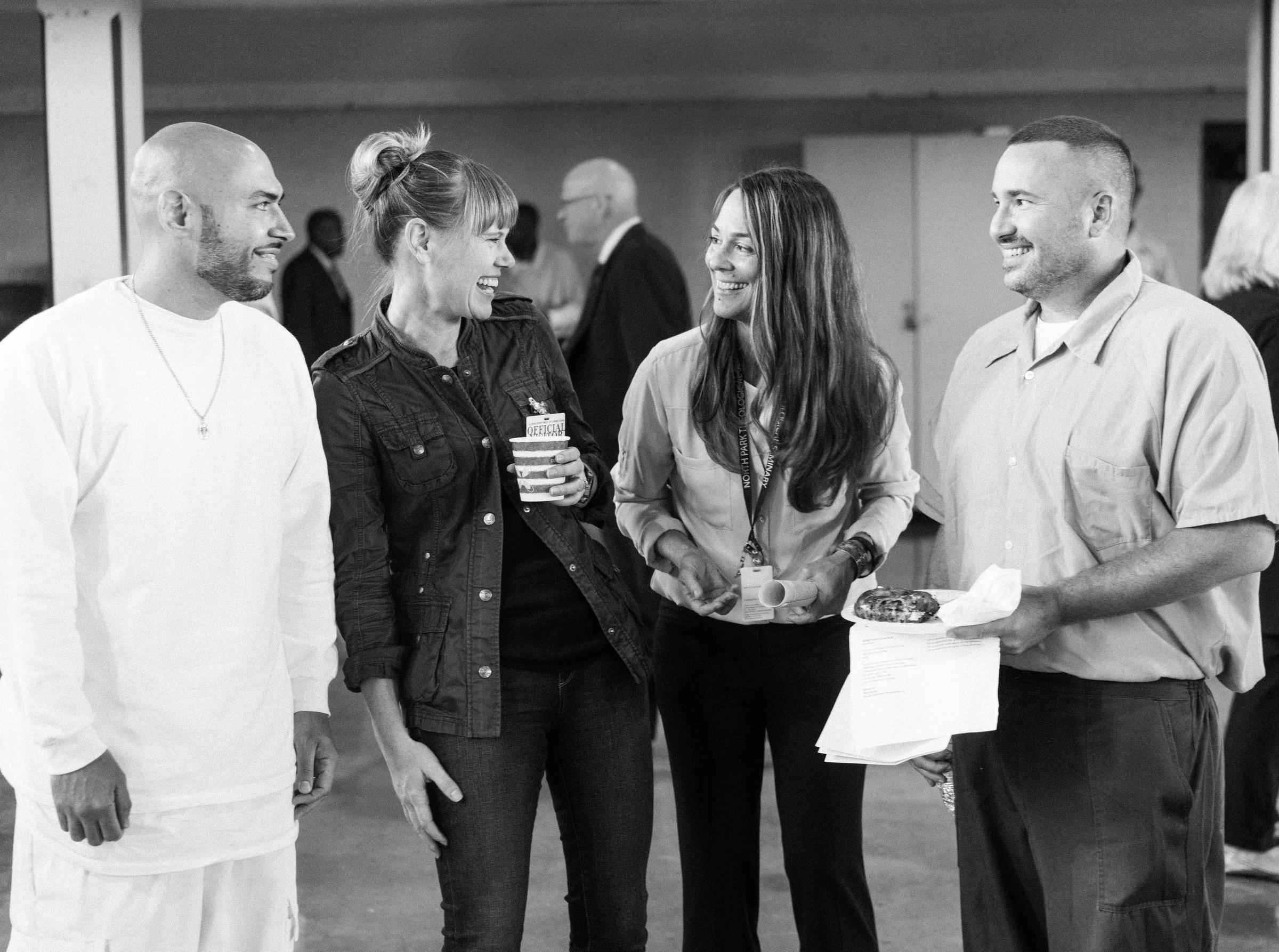

Jamal Bakr, Vickie Reddy, Michelle Clifton-Soderstrom, and Scott Moore enjoy convocation for the North Park master's degree program at Stateville Correctional Center.

Vickie Reddy is one of them, who is originally from Australia and has lived in Chicago since 2015. Her work with the organization World Relief has taken her to refugee camps in the Middle East and ICE detention centers on the US border. But at age 43, she still hasn’t earned a degree. So now, she spends two days a week inside Stateville.

“This is a community that I could not have anywhere else, and it’s teaching me something that I could not learn anywhere else. And so that part of it is equally as important as the piece of paper.”

The third thing that sets this program apart is that it’s not another vocational trade school for short-timers. To be eligible to apply for the North Park program, inmates have to have a full year of clean behavior, plus at least 15 years left on their sentence.

Rich Stempinski, who manages adult education for the Illinois Department of Corrections, points to data from Angola, Louisiana’s notorious State Penitentiary, that show a somewhat similar program drastically reduced violent incidents there.

“It gives guys who maybe not have had any hope something that motivates them, that’s positive, that’s rewarding for them," Stempinski says. "And the hope then is that they will have those discussions with their peers and be able to change the culture of Stateville.”

Ro'Derick Zavala (left) stands with his classmate Martin Barnes.

Listening to Zavala, you get the feeling that culture shift might be happening already.

“Education changes you,” he says. “There is no possible way you can sit down and read and study and do papers and do research and not be changed, because when you come up out of there, you’ve gained so much that you just want to share it. So you start to look around for people to share it with. And if a person is not on what you’re on, you don’t want to be around them. So you go and find the ones who are.

“It instills in us a confident belief that we can re-establish who we are,” Zavala says. “That’s monumental. It’s life-changing.”

Clifton-Soderstrom says 90 men applied for the 40 slots available in the North Park program. Zavala was the only one made available for an interview, because his classmates elected him to be their spokesman.

Links

- Illinois Issues: Neglect Of Local Roads Growing, Say County Engineers

- Illinois Issues: Gov. Pritzker’s Budget Address, Annotated

- Illinois Issues: How Race Factors Into Infant Mortality

- Illinois Issues: Tobacco 21 Plan - Puffed Up or Plausible?

- Illinois Issues: Tim’s Story - The Quiet Killer

- Illinois Issues: Where The End Offers A New Beginning

- Illinois Issues: Vicious Cycle Emerges With Opioid And Suicide Epidemics

- Illinois Issues: The Pritzker Agenda

- Illinois Issues: New State Laws In 2019

- Illinois Issues: Piece Of The Pot - Money And Weed In Illinois

- Illinois Issues: When Walmart Leaves Town

- Illinois Issues: Ten Years Later, Has Illinois Learned The Right Lessons From Blagojevich?